Karl Verhaeghe escaped death after a serious road traffic accident. The experience fuelled his ambition to safeguard his family business and protect the historic beer style of his home.

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

When the police came to the house where Isabelle Eeman was waiting for her husband to deliver furniture, they told her that he had been rushed to hospital and that she should go directly there if she wanted to see him alive.

Karl Verhaeghe and Isabelle were moving house from the small West Flemish village of Vichte, where Karl had lived all his life, to Aalst, a large town in East Flanders where Isabelle had grown up. Isabelle had travelled ahead by car, and was waiting for him with Karl’s brother Peter Verhaeghe who was to help unload the furniture. Karl and Isabelle had married in 2005 after meeting at a party, where she had fallen in love with his gentle spirit. “He takes into account other people,” says Isabelle. “He’s always thinking whether other people are ok.” Because they met in their forties, they decided not to have children together but to lavish their love on the next generation of their family: the children of Karl’s brother Peter and his sister Mercedes.

During Karl’s furniture run, on the E40 motorway between Kortrijk and Ghent, a fast moving jeep darted for the exit at De Pinte, cutting off a large truck in its attempt to make the turn-off. The truck swerved instinctively to avoid the jeep and smashed into the side of Karl’s van, sending his vehicle into a violent spin and ejecting him from his seat. He was propelled through the glass windscreen and landed in the middle of the motorway facing oncoming high speed traffic, ribs broken, one of his back vertebrae smashed into pieces, and completely unconscious. “I needed to see him,” says Isabelle. “To see if he was still alive.”

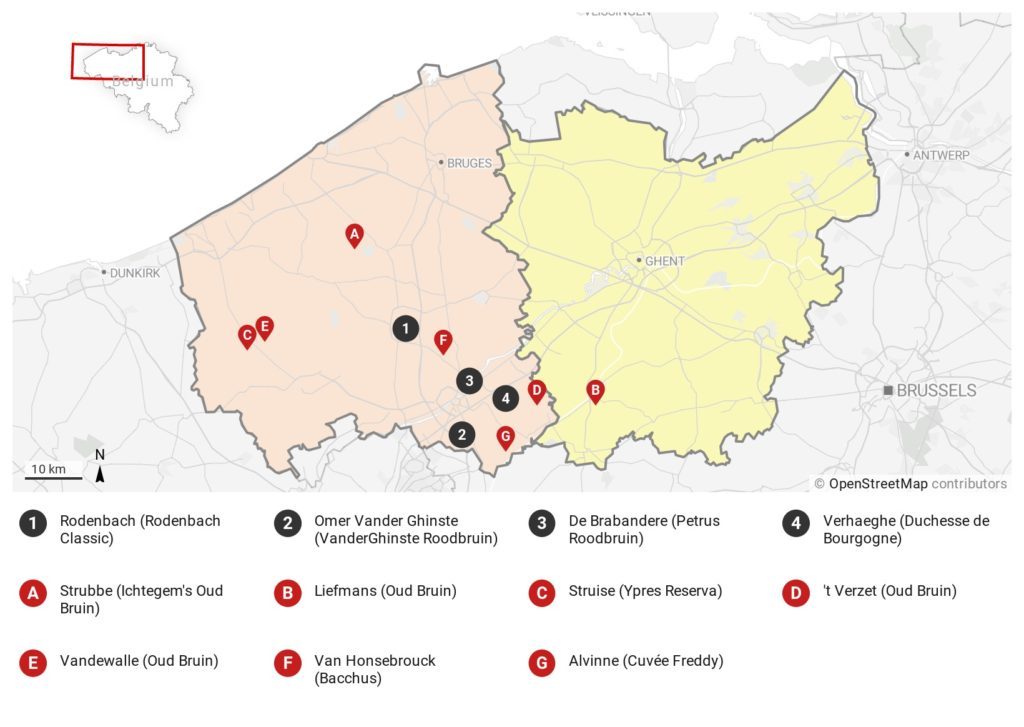

At the time of the accident in 2012, Karl Verhaeghe and his brother Peter Verhaehge were managing Brouwerij Verhaeghe, a small family brewery in South West Flanders. The region is regarded as the epicentre of one of Belgium’s indigenous styles, a beer of mixed fermentation with a sweet and sour flavour profile described—depending on who you ask—as “Flemish Red-Brown”, “Flanders Red”, or “Oud Bruin”.

Karl Verhaeghe’s serious road traffic accident left question marks about the future of Brouwerij Verhaeghe, now in its fourth generation of family ownership. Other producers of Flemish Red-Brown beer in the region were concerned not just for Karl’s health, but also for the future of the category, with only four remaining breweries producing the style in what was supposed to be the beer’s stronghold, each whose volumes of Flemish Red-Brown were decreasing year on year due to the changing beer market. Flemish Red-Brown was seen as a relic of the past, it’s sweet malt and sour fermentation flavours far removed from the clean, crisp Lagers which had gained traction with younger drinkers all over Europe. The focus was on the new and the next, not on those trying to live from tradition. Once things disappear into history, it’s often impossible to get them back.

Karl was 48-years-old at the time of his accident, a medium-built, mild-mannered man with a rosy complexion, and eyes that sparkled. He had grown up in Vichte around the brewery and had attended Sint Barbara College in Ghent between 1976 and 1982, becoming close with Nicolas Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem: a friend who would play an important role in the story of Brouwerij Verhaeghe in later years. Karl loved working at Brouwerij Verhaeghe and had been outgoing and energetic, enjoying cycling trips around the countryside of the Leie Valley on days away from work. In his mind, the brewery and the Flemish Red-Brown style were inextricably linked to his father, and his grandfather, and his great grandfather. They were a part of his identity. “It’s not a question of money,” says Karl. “It’s a question of honour. You can’t sell honour. You can’t buy honour. It’s part of myself.”

Karl Verhaeghe and Peter Verhaeghe took over the running of the brewery in May 1991 from their father Jacques. Karl took responsibility for the commercial management of the brewery and Peter lead production. The brothers had never worked together before and at times, when they crossed into each other’s territory, there were heated exchanges: Peter had opinions about marketing and sales; Karl wanted to change things in the brewhouse. In addition, the brewery was in bad physical condition and in need of serious upgrade. Old equipment needed replacing. Investment to address structural issues in the buildings was required.

Brouwerij Verhaeghe was established in 1885 by Karl’s great grandfather Paul Verhaeghe, together with his half-brother, Adolf Verhaeghe. During the First World War, they were forced to deal with a widespread economic collapse and the westward advance of German soldiers who were summarily executing Belgian civilians and deliberately destroying towns in a series of punitive actions collectively known as “The Rape of Belgium”. Paul and Adolf survived, but the brewery was dismantled, its copper repurposed for German artillery.

At the time the brewery was being rebuilt after the First World War, a train line from Eecklo to Kortrijk—Belgian Rail Line L-05—was established. This train line facilitated the building of a new station in Vichte, just a few hundred metres from the recently rebuilt Brouwerij Verhaeghe. It connected the village to Brussels and other parts of Europe. Paul Verhaeghe’s sons married into other brewing families, accumulating a network of cafés for Brouwerij Verhaeghe. By the time Léon Verhaeghe and Victor Verhaeghe took over in 1937, the brewery had become a strong regional player.

3

While it began producing Lagers like many other breweries in Belgium post World War II, Brouwerij Verhaeghe held on to its heritage, winning several awards in the 1950s for its mixed fermentation oak-aged beers. Karl and Peter’s father Jacques took control of the brewery in 1973 with his cousin, Pierre Verhaeghe, and together they continued building both their Lager and Flemish Red-Brown brands. Young Karl and Peter grew up amongst the tanks and the foeders, learning to ride their bikes on the grounds of the brewery, and listening to their father and uncle venerate the family name.

In the 1980s, at a time when Flemish Red-Brown beer was beginning to struggle commercially due to Lager’s meteoric rise, Karl’s uncle Pierre Verhaeghe—thinking of his retirement and lack of succession—wanted to sell Brouwerij Verhaeghe to Brouwerij Riva, based in Dentergem. But Karl’s father Jacques wanted to continue the business to ensure the Verhaeghe Flemish Red-Brown beers lived on, in part to honour the legacy of his own father. It was agreed that Jacques would buy Pierre’s shares in the brewery business and that Pierre could sell the rights to Riva to distribute beer in the Verhaeghe cafés owned by Pierre. Karl watched as the brewery lost an important chunk of its distribution network. It would hurt the brewery’s ability to grow volumes and build their name. But Karl also saw his father’s determination to give the next generation of Verhaeghes the chance to take the reins.

Despite the serious investment in infrastructure required, Karl and Peter Verhaeghe’s main concerns when they took over in 1991 were what they should brew. The advice Karl received from people in the region and from breweries in other parts of Belgium was to brew a “Witbier” or “Blanche”, a hazy blonde Belgian wheat ale produced with malted wheat, typically made with additions of coriander and Curaçao orange peel.

The advice was predicated on the incredible success of Hoegaarden, a Witbier which had been created by a Belgian milkman called Pierre Celis in the 1980s. In 1989, Interbrew, now Anheuser Busch Inbev, bought the brewery from Celis and the Hoegaarden Witbier started to appear in almost every café in Belgium, desired at that time for its citrus and spice flavours and a light refreshing drinkability which contrasted starkly with the darker colour and sharper acidic flavours of the Flemish Red-Brown. Hoegaarden’s commercial success prompted almost every brewery in Belgium to brew their own Witbier.

When Karl would meet with the wholesalers who distributed his beer, they would ask why he wasn’t brewing a Witbier. When he would visit Verhaeghe cafés, the tenant publicans and visiting patrons would ask when a Verhaeghe Witbier was coming. The other breweries in South West Flanders were starting to produce less Flemish Red-Brown and develop their own Witbier products.

But Karl wasn’t comfortable choosing Witbier. “It’s not a very popular beer,” he says of Flemish Red-Brown. “But it’s a beer with a lot of authenticity.” Karl Verhaeghe uses the word “authenticity” a lot. On one hand, it’s a romantic reference to traditional ways of working. On the other hand, it’s a stubborn refusal to be associated with anything of disputed origin. “To be a copy of a famous wheat beer, you can never be the best,” says Karl. “Will we brew something that’s popular but we don’t have any identity?”

The Verhaeghes invested everything into the production of a new Flemish Red-Brown beer, starting with a sweet red-brown coloured wort, which was fermented with a low attenuating ale yeast for about a week, before being transferred for further fermentation and acidification to large wooden vats known in Belgium as “foeders”.

All Flemish Red-Brown beers involve a balance of malt sweetness and flavour compounds which derive predominantly from lactic acid bacteria, although different versions can express the personality of other bacteria and wild yeast. Blending younger and older beer ensures the breweries maintain control over the levels of acidity, sweetness, and flavour intensity. Almost all are pasteurised so flavour is locked in as the blender intends and so that beers are shelf stable.

The four family brewers producing Flemish Red-Brown beer in South West Flanders—Rodenbach, Vander Ghinste, De Brabandere, and Verhaeghe—were not known for their spirit of collaboration or friendly relations. All four were producing the same type of beer in a small geographical area, often with their cafés side by side in the various towns and villages of the region. Familiarity breeds contempt.

An example in recent years was when a group of media were attending a press conference at Brouwerij Bavik in Bavikhove, who were about to announce that they would change the brewery name to their family name of De Brabandere. Just as the announcement began, the phones of the attending journalists started beeping and, checking their messages, they read that the neighbouring brewery in Bellegem who also produced Flemish Red-Brown were announcing a similar change from Bockor to Vander Ghinste. De Brabandere accused Vander Ghinste of hijacking their press conference. Vander Ghinste said it was a coincidence.

Despite all four producing the same style, each brewery produces their Flemish Red-Brown beer in different ways. The Rodenbach brewery combine older foeder beer with young top-fermented beer that has not seen wood, blending to different proportions for different products. De Brabandere create a blonde beer which is aged in foeders and then blended back with a young brown beer to the desired colour and flavour. Vander Ghinste pump a red-brown wort to a coolship where it is subjected to microbiological inoculation and spontaneous fermentation before being transferred to foeder and then blended back with young brown beer.

Verhaeghe’s differentiator was that their Flemish Red-Brown beer was the only one among the traditional producers which consisted of 100% foeder aged beer. All the others were using a young top-fermented beer to blend, but Verhaeghe’s beer would be the result of older foeder beer blended with younger foeder beer. The Verhaeghes believed this would deliver a fuller flavour than simply blending back with younger beer and that the process was a more “authentic” method—traditional and original—of conveying the personalities of their foeders. “We let the beers live their own lives in those oaken casks,” says Karl. “With the best we get at certain moments, we make a blend and present it to our customers.”

Aspiring to what he perceived as the splendour of the period of Burgundian rule in Belgium which stretched across the 15th and 16th centuries—“It was a very rich period when the Dukes of Burgundy were ruling our regions,” says Karl—the Verhaeghes decided to name their new beer after a prominent figure from that era. Mary of Burgundy was born in Brussels in 1457 and ruled over France and the Low Countries. What they didn’t know at the time they were naming the beer was that like Karl Verhaeghe, Mary of Burgundy was involved in a serious accident which affected her spine. During a falcon hunt in the woods near Wijnendale Castle—an historic residence just 45 kilometres north of where Brouwerij Verhaeghe lies today—her horse tripped, threw her in a ditch, and then landed on top of her, breaking her back. She died several weeks later from her injuries and was buried in Bruges, aged just 25.

“The Duchesse de Bourgogne” would be a beer of 6.2% ABV with a deep reddish colour, red-fruit character, a rich, full body and an intense, almost balsamic acidity, immediately drawing comparisons to the wines of Burgundy.

Karl decided to use the French version of her name rather than the Flemish “Maria van Bourgondië”, with the hope that as many people as possible might be able to pronounce it. With fewer and fewer people drinking Flemish Red-Brown beer, Karl and Peter Verhaeghe risked the brewery’s commercial viability on a niche style they felt reflected who they were. They might have been a small family brewery from a West Flemish village, but they aspired to creating a beer fit for Royal consumption.

In November of 1992, Karl and Peter Verhaeghe released the first new beer of their brewery ownership. The Duchesse de Bourgogne became known as simply, “The Duchesse”.

The village of Vichte in which Brouwerij Verhaeghe is located lies in the “Leiestreek”, a region named for the river Leie which flows from Pas-de-Calais in France into the river Scheldt at Ghent.

The river defines the region, cutting through rich agricultural land which neo-impressionist luminist painters like Émile Claus and Albijn Van den Abeele depicted in the first half of the 20th century and where walking trails and cycling routes continue to attract visitors. The river promoted the spinning and weaving of flax, creating prosperous but densely urbanised cities which are now home to large industrial parks, especially around Kortrijk, Kuurne, Harelbeke, and Waregem, where small and medium-sized companies mix with worldwide market-leaders.

The duality of the Leiestreek—understated beauty and dominating industry—extends to everything Verhaeghe. Karl is gentle and softly spoken, but rooted in the hard-edged technical business of brewing. The brewery itself is in part an historic building of protected national heritage, but in newer sections bears the grey, faceless facade of modern Belgian functionality. Brouwerij Verhaeghe was established 500 metres from the commercially astute French-speaking bourgeoisie of the Castle of Vichte but was erected through gritty Flemish work ethic. The Duchesse exhibits all the romance and heritage of slow maturation in wood, but is marketed and distributed efficiently in export markets all over the world.

When Karl was 16 years old, his uncle Josef Verhaeghe took him on a trip from the Leiestreek, 35 kilometres south west across the border to the French city of Roubaix. Josef was not an employee of the brewery, but helped out at events and cafés. “What else had he to do at the weekends but to drink a beer in pubs,” says Karl. In Roubaix, Josef and Karl participated in a beer trade fair, trying to sell some of Verhaeghe’s beer to the French café owners in attendance.

At the fair, Karl and Josef hung out with members of another Belgian family: “Mahieu” on their father’s side and “Vanuxeem” on their mother’s. The Vanuxeems were from Ploegsteert, right on the Belgium-France border and had started a brewery and wholesale beer business called Brasserie Vanuxeem, buying five local cafés and selling beer to individuals by driving from home to home in a truck they bought for deliveries. Their location gave them a strong presence in Flanders, Wallonia, and France, and Karl watched as they convinced café owners visiting the fair in Roubaix to work with Brasserie Vanuxeem.

“I was always referring myself to their success,” says Karl. “I learned a lot by seeing how they are doing it. They were one of the pioneers of exporting Belgian beers from smaller breweries to France. If they can do it, then I could also develop an export division for my brewery.” The 16 year-old Karl Verhaeghe was an energetic, confident, and ambitious young man with a flair for the commercial and the ability to learn quickly from others.

Brouwerij Verhaeghe, like many family breweries, owned several properties in the region, accumulating eight cafés over their 135-year history. As was commonplace in brewery-café relationships, they were rented out to tenants on the condition that in return for the freedom to manage the bar as they wished, the tenants could only pour Verhaeghe beers. In this way, Verhaeghe would have an automatic distribution network for the beers that they brewed. But they didn’t have the same amount of properties in the region that Brouwerij Vander Ghinste or Brouwerij De Brabandere had. Karl knew that if he could somehow improve distribution in cafés, then even in the face of Lager’s displacement of traditional styles, the Duchesse might have a better chance of survival.

Between the time when Karl Verhaeghe had visited the Roubaix trade fair with his Uncle Josef to the time he was managing Brouwerij Verhaeghe, Vanuxeem had grown their small brewery and beer delivery service into one of Belgium’s biggest beer wholesaler businesses. They now worked distributing beer from hundreds of breweries to cafés all over Belgium, and exporting large quantities of Belgian beer, particularly to France.

Vanuxeem had their own portfolio of beers, asking other Belgian breweries to produce their “Queue de Charrue” range. When the Verhaeghes were asked to produce their Flemish Red-Brown beer, Karl and Peter said yes. Karl was delighted to see how well the Queue de Charrue Oud Bruin was received in Vanuxeem’s client cafés, numbering in their hundreds across Belgium and France. If only he could engineer the same opportunities for the Duchesse.

Then, at the end of the 1990s, as the Duchesse was gaining traction, Karl Verhaeghe’s decision to persist with Flemish Red-Brown beer led to him being approached by a representative of Interbrew, now Anheuseur Busch Inbev. With the ambition of one day becoming the biggest brewer in the world, Interbrew planned on offering a portfolio of beers which covered a range of flavours to cafés everywhere. They began an initiative they called the “Belgian Beer Café” project, essentially setting up a chain of concept café-restaurants specialising in Belgian-inspired food and Belgian beers. The beer menu would consist of brands they had purchased: Hoegaarden would be their Witbier. Leffe would be their Abbey-style ale. Stella Artois would be their pilsner. But AB Inbev didn’t have a beer with the sweet and sour flavour profile of the Flemish Red-Brown.

The Duchesse de Bourgogne, a niche beer from a small brewery which wouldn’t disturb the status quo or compete with Interbrew’s beers, was invited to become a part of their portfolio for the project. It became featured in the menu of Belgian Beer Cafés in 50 cities spread out over 19 countries. Brouwerij Verhaeghe were soon signing deals with new importers around the world.

One of the countries that became aware of Brouwerij Verhaeghe’s beers through the Belgian Beer Café project was Denmark. In 2004, Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark married Mary Donaldson, an Australian marketing consultant. Their wedding took place at Copenhagen Cathedral, followed by a reception in the Fredensborg Palace on the eastern shore of Lake Esrum at which the Danish Royals served a range of Danish brewed beers. There was one non-Danish beer poured, chosen by the monarchs for its deep, rich flavours: the Duchesse de Bourgogne.

The two Marys chosen by the Danish were at the centre of attention: Mary Donaldson of Hobart, Tasmania, who had met Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark while he was attending the Sydney Olympics and whose relationship with Frederik was portrayed by the media as a modern “fairytale” romance between a prince and a commoner; and Mary of Burgundy, the Flemish Red-Brown Duchesse de Bourgogne, produced in the small Belgian village of Vichte, now in the hands of Europe’s most high-profile celebrities and Royal families. Perhaps one day, the Royals in Belgium might even take notice.

In the same year as the Danish Royal wedding, a post appeared on the Burgundian Babbel Belt, a forum for Belgian beer enthusiasts on the internet before other beer rating sites and social media platforms became ubiquitous.

Some users of the forum—international beer enthusiasts seeking authentic Belgian beer experiences—accused certain Belgian brewers of using aspartame and saccharin in their beer, artificial sweeteners which can be more than 200 times sweeter than sucrose. The discussion was led by a user with the handle “Loren”: “No one said yes/no about this in the Duchesse, so I’ll assume it’s in there. Since it nearly made me vomit.”

The forum post came to the attention of Karl Verhaeghe. He was angry and began typing: “Quite astonished by the content of the messages out of your hand,” he wrote. He explained the heritage of Brouwerij Verhaeghe and stated categorically that the brewery did not use, and had no intention of using aspartame or saccharin or any such related products in the Duchesse de Bourgogne or any of their other beers. “I was deeply hurt by reading that critic,” says Karl. “High standards are the best warranty for the next generations. We don’t spoil that because it’s easy or cheaper.”

Back in Belgium, the four family breweries in the region who produced Flemish Red-Brown beer began talking to each other behind the scenes. In order to counter the fall in the domestic interest in Flemish Red-Brown and to protect the beer from incorrect assumptions such as the ones Karl had encountered in the Burgundian Babble Belt forum, they were preparing an application to the European Union for recognition of their beer as a regional beer style under the Protected Designation of Origin rules. They agreed they needed to work together. “You can’t claim a beer style with only one brewery,” says Karl Verhaeghe.

In 2012, Brouwerij Rodenbach, Brouwerij Verhaeghe, Brouwerij De Brabandere, and Brouwerij Vander Ghinste decided to come together to organise a showcase of Flemish Red-Brown beers, teaming up with the local tourist board who were hoping to bring people to a region becoming more and more industrial and promote the culinary specialties of the Leie valley, some of which were being lost. The event, which they called “Rondje Roodbruin”, or “Red-Brown Tour” in English, would see the four breweries opening their doors on the same day, providing entertainment, arranging tours, and offering free samples of their Flemish Red-Brown beers.

The first year of the Rondje Roodbruin was also the year of Karl’s road traffic accident, when he was thrown through the front windscreen of his van onto the oncoming traffic of the E40 motorway. The emergency services who arrived shortly thereafter rushed him to the University Hospital in the nearby city of Ghent. Because of the expert medical attention he received, Karl survived, undergoing a series of operations over the course of months, including having an artificial back bone inserted into his spine.

So central was the brewery to Karl’s identity that there was never a question in his mind that he would not return to work. Isabelle, Peter, and Mercedes understood that Karl could not live without Brouwerij Verhaeghe and made arrangements for him to get back to his desk. But on the first day he came back to the office since leaving the hospital, he struggled to maneuver his wheelchair. He couldn’t manage to take documents out of the filing cabinet. He became exhausted at the slightest of physical tasks. “I can’t hide it,” he says. “The frustration was great. To be dependent for even the slightest thing in life is not so easy.”

Then the Verhaeghes buried their mother, Marie-Thérèse de Romsée, aged 73 when she passed away. The family became closer, working around the clock to make sure the brewery survived after Karl’s accident. Peter had already been joined in the brewery by their sister Mercedes Verhaeghe. “It’s a great strength to see the relationship between my sister and my brother and know who can you rely on,” says Karl. “You know in those moments what you mean to each other.”

Karl’s wife Isabelle decided to stop working full-time at her job as a Project Manager for a large Belgian Bank and began working part-time for a year at Brouwerij Verhaeghe to help Peter and Mercedes. “We knew quite well that we had to work together as a team,” says Isabelle. “To get through it.” Isabelle took on some of Karl’s responsibilities, managing relationships with importers, distributors, and hospitality clients, and focusing on the commercial affairs of the brewery. “My wife was coming here every day,” says Karl. “That was the happiest moment during the day for me.”

Karl changed his routine. He began waking up at 4.30am every morning for appointments with a physical therapist before undertaking an extra gym session at 8am. He arrived into the brewery most mornings around 10am, working until 7pm. When he went home, he was exhausted, and went to bed early. He did this 6 days a week, and on Sundays, he worked in the mornings on brewery affairs from his home computer. Soon, he could move his legs a little, and after a few years, was walking short distances on his own with the aid of a walking stick. The progress gave him some of his independence back, but he struggled with his energy levels and his pace in dealing with important export clients.

The Rondje Roodbruin events had continued every two years as the four family breweries persisted in their dialogue for the sake of their individual Flemish Red-Brown brands. But while the events were well attended, the brewers were unable to prove through point of sale material or press articles that the generic name “Vlaams Rood Bruin” was known for a sufficiently long time and were forced to withdraw their application for protection of the name. “The style exists for many centuries, but doesn’t have as unique a name as Geuze,” says Karl. “We have still to work to create a unique name for that beer style.”

Because there was no motivation to work together after the name protection application had been rejected, and because the local tourist board were keen to financially support other projects, the fourth edition of the Rondje Roodbruin was to be the last.

In Brouwerij Verhaeghe, Peter was taking care of production and Mercedes led accounting and administration tasks. But Isabelle was soon to return to her job at the bank full-time, meaning Karl would be left with all the commercial duties on his own: keeping the Duchesse on the shelves of shops, in the fridges of cafés, and in people’s minds. Without this constant, exhausting push, all of the family’s work would be in vain. Unless Karl could find someone to help with the export business he had been responsible for before his accident, the Duchesse—and the legacy of this generation of Verhaeghes—would be destined to fail.

The accident drove Karl to thinking more not only of his family—his brother Peter, his sister Mercedes, and his wife Isabelle—but about the people he had been close to in his life, and he decided to reconnect with friends he had not seen in years. In 2013, he called Nicolas Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem who had gone to school with him in the early 80s. “They’ve been connected for a long time,” says Isabelle. “It’s not because you are good friends that you need to see each other every month.” They arranged to meet to catch up, and when Karl visited their house in Wavre Limal, he met Nicolas’s son for the first time.

Amaury Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem was dark-haired, handsome, and smooth-talking, studying Marketing at the L’École Pratique Des Hautes Études Commerciales, a University College in Brussels specialising in commercial studies. During his conversations with Amaury, Karl saw in him an appetite to learn and a passion for commercial risk-taking similar to his own, as well as an innate energy which Karl had lost after the accident. Karl invited Amaury to take a part-time student job at Brouwerij Verhaeghe as “Community Manager”, a role Amaury could combine with his studies which would involve managing social media campaigns.

Amaury Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem’s final degree assessment involved organising a major event. He planned a Gala Party in Brussels to promote “Wheeling around the World”, an organisation founded by paraplegic globetrotter Alexandre Bodart Pinto which aims to improve travel for people with disabilities.

The day before the scheduled event, however, on Tuesday 22 March 2016, twin bomb blasts struck the main terminal of Brussels Airport. Another explosion hit the Maelbeek metro station in the city centre, close to several European Union institutions. Thirty-two people died in the three explosions, and more than 300 were injured. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) claimed responsibility for the attacks. The city was shut down while authorities hunted for the terrorists. Amaury’s event was cancelled.

Shortly after the terrorist attacks, Amaury was informed by his college that, because he hadn’t organised an event and submitted his dissertation, he would not be awarded his degree. Pleading for some extra time based on the exceptional circumstances, Amaury asked if he could undergo a different project and submit another dissertation. The college gave him three weeks.

Amaury was still assisting Brouwerij Verhaeghe as “Community Manager” and he mentioned his predicament to Karl Verhaeghe. Karl suggested that he build his dissertation around a marketing plan for the Duchesse de Bourgogne. The pair worked together on Amaury’s project for the following three weeks. In his plan, Amaury examined the history of Brouwerij Verhaeghe, undertaking business assessments and market analyses. The document centred around plans to create new branding across point of sale items such as glasses and beer mats, and to launch what Amaury describes as a “Duchesse Gamma”, a range of beers based on their most famous product.

Around that time, a Ukranian importer organised a beer festival of imported brands to Kyiv. Brouwerij Verhaeghe were invited. Because Isabelle was no longer working at the brewery and his own mobility issues made it difficult, Karl asked Amaury to represent the Verhaeghe beers in the Ukraine. Amaury travelled to Kiev with a long list of experienced industry figures from other Belgian breweries, including Marco Passarella, the Sales and Export Manager from Brouwerij St Bernardus, one of the most prominent and successful family breweries in West Flanders. Karl had known Passarella for years and hearing he was also attending in Ukraine, asked him to look out for Amaury on the trip. When they returned to Belgium, Passarella called Karl Verhaeghe to tell him that if Brouwerij Verhaeghe didn’t hire Amaury for export sales, then St Bernardus would.

It was agreed that if Amaury passed his degree, that he would start working at Brouwerij Verhaeghe and Karl would buy him a car for sales calls and export meetings. He would find out his results on the day that he was working the bar at Brouwerij Verhaeghe’s booth for the Belgian beer weekend festival in Brussels’ Grand Place. He kept his eye on the clock the whole way through his shift, his friend eventually calling him at seven o’clock in the evening to tell him he had passed. Amaury was delighted and immediately told Karl about his results. “That’s good,” said Karl. “Because I’ve already bought you the car.”

Amaury was now the Export and Marketing Manager at Brouwerij Verhaeghe and threw himself into his job, travelling all around the world to evangelise about the Duchesse. In 2017, he became a member of the Marketing Committee of the Belgian Family Brewers, a non-profit association of 21 Belgian family breweries which have been brewing beer in Belgium for at least 50 years non-stop.

Karl, Peter and Mercedes worked closely with Amaury, using his university project plan as a foundation to develop a new “Duchesse Gamma”, effectively rebranding the “Echt Kriekenbier”—their unpronounceable mixed fermentation fruit beer produced using real cherries—as the Duchesse Cherry, and rounding out the range with a new beer called the Chocolate Duchesse Cherry, which featured the addition of natural cocoa distillate. The marketing copy on their website for each of the three brands reads: “The one and only”; “The famous Duchesse with a touch of cherry”; and “When a touch of cherry just isn’t enough”.

Karl and Amaury are currently working on another Duchesse product for export markets, a lower ABV version called the Duchesse Petite which they plan to package in cans at somewhere between 4 and 5% ABV (as opposed to the Duchesse’s 6.2% ABV). Through changes after the accident, and by being open to Amaury’s suggestions, Karl learned that he could maintain the authenticity of the Duchesse—and indeed make it more relevant—by changing how it was offered to drinkers to suit modern demand. In these new beers, the duality of the Leiestreek was on show once again, as traditional methods underscored the addition of different flavours.

At a time when most Belgian breweries were experiencing a retraction in their export to the United States, Verhaeghe’s Duchesse de Bourgogne—with the assistance of their US importers, D&V International—were experiencing growth.

In 1991, when Karl and Peter Verhaeghe took over their family brewery, it was producing around 1,000 HL of beer in a year. In 2020, despite the coronavirus pandemic, Brouwerij Verhaeghe will produce around 13,000 HL. The Duchesse de Bourgogne makes up 80% of this production, with 85% of all their beer being exported outside of Belgium. Changes to the 130 year old building are planned for the future, limited by the property’s status as protected heritage and the demanding space requirements of its foeders, the old brewing room destined to become a space to host cultural events.

Karl Verhaeghe continues to attend his physical therapy sessions and work with Peter, Mercedes, Isabelle, Amaury, and the 15 staff at Brouwerij Verhaeghe on production, marketing, and sales. There’s no indication yet as to who might take responsibility for the Duchesse in the next generation. While Karl and Isabelle decided not to have children because of their age when they met, Peter Verhaeghe and his wife Hilde Cauchie are parents to 21 year old Arthur and 15 year old Jozefin, and Mercedes Verhaeghe and Olivier Vanden Borre have a 22 year old daughter, Morgane and an 18 year old son, Casimir. “It’s a bit too early to say,” says Isabelle. “But, of course, we hope that some of the children from Mercedes and Peter will be interested.”

The Verhaeghes continue to run the business together and while there are risks inherent in export market dependence and economic reliance on one product, the decision to persist with regional heritage in modern times seems to have paid off. “Tradition does not mean you cannot evolve with modern techniques,” says Isabelle. “It’s a mental tradition. A state of mind. If you look to the past, you are with your back to the future.”

In 2018, Karl Verhaeghe received a message from the Belgian Royal Palace inviting him and Isabelle to represent Brouwerij Verhaeghe on an economic mission to Canada. Neither had any idea how or why they had been invited. “It was a mystery,” says Isabelle. “My reaction was if you have the chance, take it.” On the morning of 16 March 2018, with temperatures below freezing at -5°C, Karl Verhaeghe signed an exclusive distribution deal with McClelland Premium Imports on behalf of Brouwerij Verhaeghe which would see sales of Duchesse grow in Canada. The official signing ceremony took place at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal and was witnessed by King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium.

The Royal visits continued, recognition of Brouwerij Verhaeghe’s role in preserving one of Belgium’s regional beer styles and an acknowledgement of the brewery’s growing international reputation. Last year, Karl travelled with Isabelle and Amaury on another Royal Mission with the Belgian King and Queen, this time to South Korea. Amaury then represented Brouwerij Verhaeghe on Belgian Royal Missions to Mexico and China, visits which improved export collaborations.

Brouwerij Verhaeghe recently installed a brand new modern brewing system, an automatic GEA Huppmann brewhouse which enables several 100 HL brews per day. The high specification kit delivers wort to the older part of the brewery, 44 oak foeders, each between 63 HL and 185 HL in size. The new stainless steel feeding the old wood is another example of the dual identity of the Leiestreek, an illustration of the “mental tradition” described by Isabelle.

On the hatch of this new brewing kettle, the manufacturers have printed Brouwerij Verhaeghe’s logo, a coat of arms linked to both the crest of the Castle in Vichte and that of the German town of Ommersheim with which Vichte is twinned. The coat of arms features a lion on either side and a crown on top, similar to the lions and crown that appear on the coat of arms of Belgium. From a distance, it looks as if the brewery logo is an emblem of Belgian Royalty, existing solely to honour a King or a Queen, or maybe even a Duchess.

*