It’s a brisk October afternoon outside a Manchester Travelodge and Pierre Tilquin opens up another bottle of ‘Mariana Trench’ in the back of his parked van. It’s a Transpacific Pale Ale of 5.3% ABV from a West London brewery called Weird Beard Brewing Company. Bryan Spooner and Natasha Wolf from Weird Beard are sitting beside Pierre in the van, pouring the beer for him and getting to know the Belgian blender.

They’re all taking a short break from the 2015 Independent Manchester Beer Convention (Indy Man Beer Con), one of the UK’s most respected beer festivals at which Tilquin has been invited to host tastings of his Oude Mure Tilquin a l’Ancienne, a spontaneously fermented fruit beer produced by fermenting 350g of blackberries on each litre of lambic. He’s the only Belgian of the 46 breweries in attendance and the only Geuze producer at the festival.

Fast forward to May 2016 and Weird Beard are in Belgium pouring at Tilquin’s own event. It’s the second edition of his English beer festival for which 13 of England’s most high profile breweries have travelled to the small village of Bierghes to pour their most interesting beers. In total, 1,100 people attend over the course of the weekend and the Belgians and English mix with visitors from as far away as Scandanavia and the United States.

WARM AND FLAT

Despite now showcasing beers from England at his blending facility in Belgium, Tilquin’s initial encounters with beer from England were far from enthusiastic. “When I was 18 I was really into music and I would go to the UK with some friends to buy records,” he says. “We would buy rare records in London and then taste some English beers in the afternoon. A lot of them were warm and flat. Many had less taste than Jupiler. It was not nice. I was afraid people in Belgium would think the same and stay away from this festival.”

Even if culturally misunderstood or perhaps poorly served to a young Tilquin, it’s clear that these English beers drew out an initial impression on his part which was negative. That perception about English beer is still widely held in Belgium today. It’s precisely for that reason the festival is important.

“I’m a fan of English beers now,” says Pierre. “They are more interesting, more subtle and more delicate than what the U.S. breweries are doing. In the U.S. they go for the most bitter, the most sour, the most extreme. The English craft beer scene has become very interesting in the last 5 years, completely renewing since the arrival of the Kernel. You can really see the British spirit in the balance of their beers. But there’s craziness too. Look at ‘Bearded Lady’, an imperial stout from Magic Rock.”

The shared brewing history and geographical proximity of the two countries are also important considerations for Tilquin in exploring the relationship between Belgium and England at this festival. “We are so close,” he says. “We can have fresh beers from England. Many of the U.S. beers are too old. I always have to make sure that I look at the date on the bottles of U.S. beer in the shop.”

ORIGINS: TOER DE GEUZE

If Tilquin has respect for the breweries he has invited from England, there’s a kind of fan-boy admiration in the opposite direction.

“I came to visit the blendery 5 years ago with some friends,” says Dominic Driscoll, the Production Manager at Thornbridge. “He was too busy at the time to meet with us so we asked if we could just buy some of his beer. He asked us to wait for 10 minutes and when he came back he gave us a two hour tour. We left some Thornbridge beers when we were leaving and he ran out after us to tell us how much he loved our brewery.”

Tilquin met several of these English breweries for the first time two years ago at De Molen’s Borefts beer festival in the Netherlands and again on a subsequent weekend trip to London. While Tilquin was preparing for the bi-annual Toer de Geuze – an open day for the lambic and geuze producers of the Pajottenland and Senne Valley – the brewers from Thornbridge and the Kernel he had met at Borefts got in touch and offered to come along and help him at the event. “Pierre took us up on our offer,” says Dominic. “He told us we should bring some kegs if we were coming.”

For Tilquin, it made perfect sense. “I thought that it would be a good idea to let them pour when they came over for the Toer de Geuze in 2015,” he says. “My open door events hadn’t been very well attended and it’s not easy to drink lambic and geuze all day. Here we could do something new.”

THE ONLY WALLOON

In the same way that bringing breweries from England to Belgium offers something different, so too is Tilquin’s blending operation unique.

Originally from Namur and now basing production in Bierghes, he’s the only blender of lambic beers in the French speaking southern part of Belgium. It’s central to his identity. The first thing you’ll find on a Google search of his gueuzerie is the statement: “The only Walloon Gueuze.” The name ‘Gueuzerie’ itself is his own invention. His Flemish colleagues use the historical moniker ‘Geuzestekerij’.

Tilquin’s journey to blending began in bio-engineering and animal breeding and continued with a PhD in statistical genetics. Fed up with the years of study involved, he yearned for something more practical. He worked for over a year at the Huyghe brewery in Melle, famous for their Delirium Tremens beer, and then six month periods of work experience at each of Drie Fonteinen and Cantillon equipped him with the experience and contacts to dream. High rents in Brussels, together with some support from the Walloon region resulted in him setting up shop in the village of Bierghes (Rebecq).

TILQUIN BLENDING

At the heart of Tilquin’s work is the purchasing of wort from lambic producers in the region which he then ferments and ages as lambic in his facility and blends to his own preference. “There are a lot of myths about blending,” says Pierre. “In reality, I take my lambic at the ages I think are best from each producer and put them together in the way I want.”

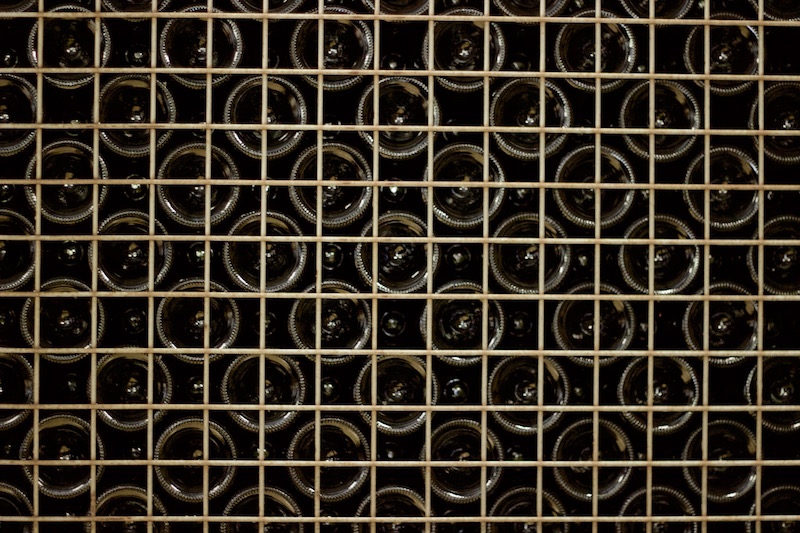

“I use 50% of 1 year old, 30% of 2 years old, and 20% of 3 years old,” he says. “I use Boon and Lindemans as 1 year old, then Lindemans and Girardin as 2 years old, and Girardin and Cantillon as 3 years old. That’s my blend.”

BELGIAN INSPIRED

The festival is by no means a big money spinner for the English breweries but so influenced by Belgian beer culture and so respectful of Tilquin are they that confirmations were quick. “This year I invited 13 breweries hoping that 10 would accept,” says Pierre. “All 13 said yes.”

One of those 13 was Buxton Brewery based in Derbyshire who Tilquin also met for the first time in Manchester last year. “Pierre visited our brewery during the weekend of Indy Man Beer Con,” says Head Brewer, Colin Stronge. “We hung out together for most of that festival. I consider myself very Belgian inspired as a brewer.”

Wild Beer Company are based in Somerset and specialise in using wood to produce wild beers. “When we decided to start up the brewery, we came to Belgium,” says Founder Brett Ellis, who worked in the wine regions of California before moving to England. “We were drinking Orval in Brussels café Poechenellekelder and they were charging 50 cents extra for every 6 months it had aged. That blew my mind. We were discovering Rodenbach, Cantillon and even back in England, the Gale’s Prize Old Ale. Now we focus on flavours which evolve and which go really well with food.”

Chris Heaney of London’s Partizan Brewing pours an IPA Brett Apricot at the festival, a fusion of styles combining their love of American hops, their fascination with highly attenuating yeast strains, the wild characteristics of Brettanomyces and the complexity of working with fruit. “We wanted the Brett to fully ferment one of our earlier incarnations of this beer but it stopped fermenting half way through,” he says. “So we pitched a Saison yeast to finish it and then propagated that mixed culture. It’s an incredible strain. We call it the Chuck Norris of yeast.”

LAMBIC POLITICS

The idiosyncratic and multi-layered nature of Belgium’s linguistic, geographical and historical make-up meant Tilquin had to overcome several barriers when first starting out. Aside from the difficulty of having to finance a business for 3 years without any income until his lambic had aged sufficiently to blend, he was forced to navigate through the added political quagmire that is the Belgian beer world and in particular, the close-knit community of lambic brewers and blenders.

“I encountered quite a lot of resistance,” says Pierre. “At the beginning Girardin didn’t want me. De Cam and 3 Fonteinen were concerned about how our location would affect the perception of lambic. Now we’re all good friends and we’re members of HORAL together.” HORAL is the ‘High Council for Artisanal Lambic Beers’, a non-profit membership organisation whose goal is to promote lambic beers.

He may be situated in Wallonia but Tilquin is in no doubt that the microflora and activity of wild yeast is similar to that being produced by the other lambic breweries in Brussels and Flanders. “We’re 200 metres from the language border in Belgium and we’re at the edge of the Senne Valley,” says Pierre. “I have always said that Brettanomyces can speak both languages.”