This year, Duvel Moortgat celebrates its 150th anniversary. The company owes much of its success to its Belgian Golden Strong Ale, but how exactly has Duvel become one of the most iconic beers in Belgium?

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney, Ciara Elizabeth Smyth, and Eoghan Walsh.

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “War Chest” series. Read more.

A man arrives in his car and buzzes into a warehouse in the dead of night. Leather-jacketed and with his guitar strung over his shoulder, we see it is well-known Belgian musician Jan Paternoster walking through a modern brewhouse. He nods to brewers on the night shift and a sample of golden beer is pulled from a tank as he passes. He uses a security pass with a red gothic “D” to swipe through a door—the instantly recognisable branding of Duvel Moortgat. Paternoster descends down a red-neon staircase into the rijpingskelder. This isn’t his first time here.

In the maturation cellar, he finds another popular Belgian musician, Daniël “Daan” Stuyven, playing music. The pair share a few words—“They’re almost ready,” says Daan. “Let’s try and shake them up,” replies Paternoster—before a changing of the guard. Paternoster plugs his electric guitar into speakers and blasts out a rock solo riff as the camera pans up to his audience: 90 back-lit display rows containing thousands of steinie bottles of Duvel, each rattling along to the music.

It’s not Duvel’s funniest advert. Nor is it their most dramatic or cinematic. But this promotional film from 2016 had a singularity of message that resonated deeply. It told viewers that Duvel is a beer that receives the utmost care and attention. And it told us that production of Duvel takes 90 days, longer than virtually all other top-fermented beers made in Belgium. Duvel Moortgat used a reworked version of one of Daan’s tracks—a song called “Icon”—to demonstrate that the beer is incited into being through a rousing creative process.

This year Duvel Moortgat celebrates its 150th anniversary and the occasion is being marked with the release of a new beer. Duvel 6.66% follows Duvel Green, Duvel Single, Duvel on Tap, Duvel Tripel Hop, and Duvel Barrel Aged. However, as these line extensions mount up, the original remains totemic of the brewery. What has been behind the success of the mother beer? Just how did Duvel become so iconic?

I. Genesis

Duvel was originally launched by Brouwerij Moortgat in 1923 under the name Victory Ale. Some stories suggest that its name derived from the initials of the brothers who ran the brewery: “V” for Victor and “A” for Albert. But its name was most likely influenced by the end of the First World War, as were a slew of other ales: Cabby’s Pale Ale, Cheerio Pale Ale, Navy’s Pale Ale, and from Brasserie Maurice Lannoy in Menin, Liberator Pale Ale. Chris Bauweraerts, Co-Founder of the Achouffe brewery which is now a part of the Duvel Moortgat group, frames this trend in the 1920s as a simple choice for Belgians after the First World War between a German Pilsner and an English Ale. Of the styles most associated with the two nations at the heart of the conflict, which would Belgians choose? “You drink the beer style of the Liberator,” says Bauweraerts.

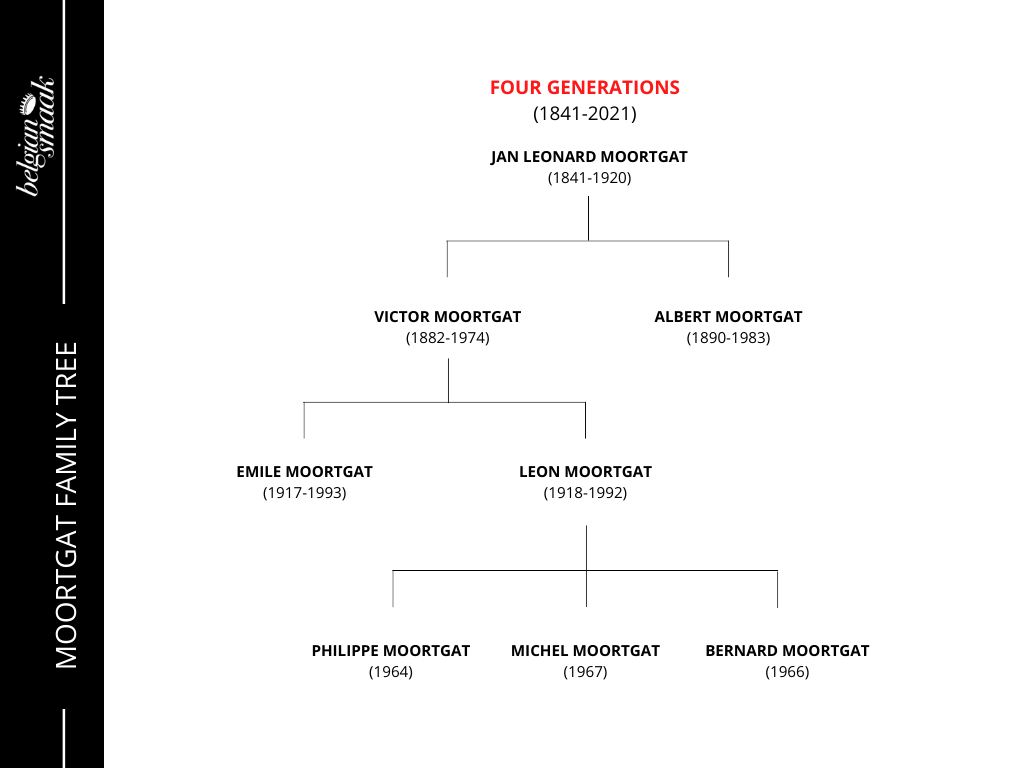

In 1914, the same year as World World One broke out, Albert and Victor’s brother Jozef, who had been running Brouwerij Moortgat, died suddenly. Albert’s father Jan Leonard Moortgat was getting too old to manage the brewery he had established in 1871, and the 43-year old family business was in danger of failing. So, at the age of 20, Albert Moortgat came on board to lead his family brewery and by 1919, his brother Victor Moortgat, living in Brussels up to that point, was back in the village of Breendonk to help. Their father officially handed over control of the family brewery to his two sons: Albert in production; and Victor running commercial affairs. They needed a new beer for their generation.

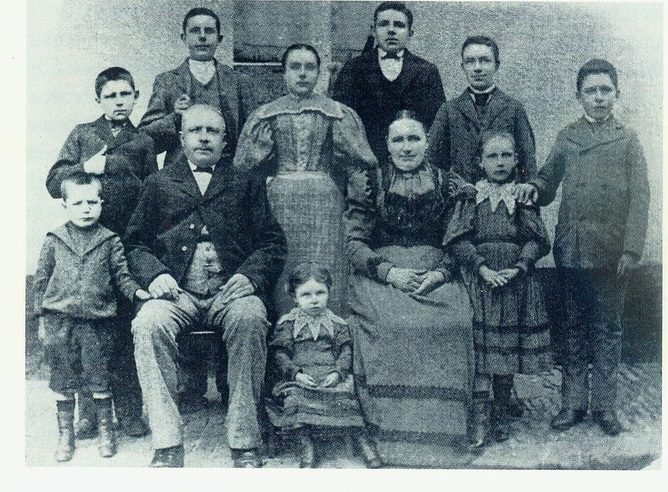

From left to right, first row: Albert, Jan Leonard, little Alice, Maria Hendrika, Louise;

Second row:: Edward, Karel, Leontien, Jozef, Gustaaf, Victor.

Photographer unknown. Copyright: Public Domain

The foundation for Duvel’s iconic status is the origin story of its yeast, one represented in Duvel Moortgat’s marketing literature as an odyssey, unique and epic. Unlike other family breweries who may have secured strains from yeast banks at Belgian universities, it’s claimed by Duvel Moortgat that Albert Moortgat travelled to Scotland to source a yeast for use in his Victory Ale that he believed to be special or particularly desirable. A comic strip published by Duvel Moortgat purports to tell the story of that journey. In the comic strip, Albert is seen travelling with an aluminium milk can in which the yeast was supposedly transported from William McEwan’s Fountain Brewery in Edinburgh.

However, there are some who believe Duvel’s origin story to be different. Chris Bauweraerts, the co-creator of Chouffe, is one such doubter. Bauweraerts believes that the yeast was secured not from William McEwan’s Brewery, but from William Younger’s Brewery. The confusion is understandable: In 1931 Younger’s merged with McEwan’s to form new entity Scottish Brewers, which in turn merged with Newcastle Breweries in 1960 to form Scottish & Newcastle.

The reason for Bauweraerts’ suspicion is that William Younger’s beers were being imported into Belgium at the time by John Martin, whose business was located 30 kilometres from Moortgat’s brewery in Breendonk. “Brewers come together,” says Bauweraerts. “I can imagine he asked John Martin, can you bring me in contact with the brewery that you import from Scotland, and that was William Younger’s.”

Belgian journalist Katrien Bruyland has suggested in her reporting that Albert Moortgat may not have gone to Edinburgh at all, but rather harvested yeast from bottles of William Younger’s beer at home, available through John Martin’s import business in Belgium.

“The strong ale being live beer, it makes no sense that a technically skilled, perfectionist brewer would choose a time-consuming journey to harvest yeast in Edinburgh instead of cultivating yeast from a bottle of imported ale,” wrote Bruyland in Issue 20 of Original Gravity magazine. “However, Moortgat worked with Professor P. Biourge, a world-renowned yeast expert, who is said to have combined several strains from the Edinburgh yeast to be used in Victory Ale.”

It is not definitively clear how Albert Moortgat secured the yeast. But these conflicting stories only feed into the mythology around Duvel’s original strain compared with the more prosaic provenance of the house strains of other family breweries. What is clear is that Victory Ale would have tasted totally different to what beer drinkers now know as Duvel. Today’s Duvel is a clean, highly carbonated ale of 8.5% ABV with Saaz Saaz and Styrian Goldings hop aromas of white pepper and freshly cut grass, flavours of biscuit dough, honey, citrus peel, and dried herbs, and a dry, medium-bitter finish. Duvel Moortgat’s Quality Director Dimitri Staelens suggests the original Victory Ale may have been closer at that time to a Belgian Scotch Ale than to the beer style modern-day Duvel would come to define: Belgian Golden Strong Ale.

During a tasting at the brewery in the 1920s, a local shoemaker named Van De Wouwer is said by Duvel Moortgat to have exclaimed that the beer was “nen echten Duvel”: in the region’s dialect, “a real Devil”. Whether that is true or not, the Moortgats rechristened the beer with a new name endowing the product with a dangerous, naughty, and alluring brand that helped build its iconic reputation. The future was looking bright for Brouwerij Moortgat. But for the village of Breendonk where the brewery is located, things were about to get darker.

II. Allegiances

Less than 4 kilometres from Duvel Moortgat’s brewery lies Fort Breendonk, a former Nazi prison camp used in the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Today, it’s a symbol of the cruelty of the Nazi regime, a place where thousands of imprisoned members of Belgium’s Jewish community and resistance were starved, forced into meaningless labour, and subjected to frequent physical punishment beatings by officers of the Flemish SS. A section of Fort Breendonk was used as a transit camp for Jews being sent to death camps in Eastern Europe, such as the concentration camp at Auschwitz.

When the Second World War broke out, Albert Moortgat was a politician as well as a brewer. He had served as Mayor of Breendonk since 1921 (and would hold office until 1944). But he had changed parties since his initial election; he was no longer a member of the Catholic Party, but had joined the Vlaams National Verbond (the Flemish National Union). “[The Vlaams Nationaal Verbond] was an anti-Belgian authoritarian party,” says Patrick Nefor, the Head of Documentation at Belgium’s War Heritage Institute. “You can consider it as a fascist party. It was an openly collaborationist party and Moortgat was a member of the party.”

According to Nefor—who wrote the book Breendonk, 1940-1945: De geschiedenis (which includes a section about Albert Moortgat)—Belgian police had amassed evidence of Albert Moortgat’s changing political leanings: pictures taken during the war of some of Albert Moortgat’s daughters with German officers; a subscription to a weekly National Socialist newspaper; testimony from Albert Moortgat’s sister-in-law that he had a portrait of the Führer in his dining room; and relayed conversations from witnesses in Moorgat pubs in Breendonk in which Albert Moortgat supposedly expressed confidence in a German victory. The Moortgat brewery advertised its beers during WWII under the slogan “Eén volk, één Staat, één Bier” (“One people, One Nation, One Beer), strongly echoing Adolf Hitler’s slogan “Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer” (“One People, One Nation, One Leader”).

Albert Moortgat was arrested in September 1944 during the Allied liberation of Belgium. On 28 March 1946, he was sentenced by a military tribunal in Mechelen to four years imprisonment for collaboration with the Nazis (Nefor’s research suggests Albert Moortgat appealed, after which an extra year was added to his sentence). He continued to protest his innocence after the war, arguing that all Mayors would have had to form close relationships with the Germans to protect the inhabitants of their towns and villages. He was released from prison early at the end of August 1947. Albert Moortgat’s political career was finished, but he still had a brewery to run.

With its brewery a stone’s throw from Fort Breendonk and its original creator imprisoned for collaboration with the Nazis, Duvel’s past is a cautionary reminder of some of Belgium’s darkest days, history that remains contested today in certain sections of Flemish society.

Emerging from wartime privation, the third generation of the Moortgat family to run the brewery—Victor’s sons Emile and Leon (with some assistance later from Albert’s sons Marcel and Bert)—presided over growth and prosperity in the post-war years. To their existing Bel and Vedett lagers, they added the Maredsous brand of Abbey-style Ales after securing a licence from the Maredsous Abbey in 1963. And they landed a lucrative bottling and distribution contract with Danish beer giant Tuborg, allowing them to sell their beers into new markets where Tuborg already had a hold.

However, it was in the 1960s and early 1970s that saw the emergence of the beer that would become the iconic Duvel we know today. Emile Moortgat, a member of the third generation of the Moortgats, formed a strong allegiance with Professor Jean De Clerck, one of the brewing world’s most influential scientists and scholars. Brussels born De Clerck founded the European Brewing Convention, wrote a canonical two-volume work called Textbook for Brewing, and assisted the monks at the Abbey of Notre Dame de Scourmont to create the famous Belgian Dark Strong Trappist Ale, Chimay Blue. De Clerck was the best in his field. And that’s why the Moortgats hired him.

In the 1960s, De Clerck worked to isolate strains from Duvel’s original Scottish yeast to deliver a cleaner, purer beer. He is also thought to be responsible for lightening the colour so it became blonde, at a time when paler beers were becoming more and more in demand in Belgium. This was also the period that the brewery introduced the now-iconic Duvel glass. Its voluptuous ballon was one of the first tulips to appear in Belgium, sharing functional and aesthetic elements with the Burgundy wine sampling glass. It was also the era of Duvel’s first commercial forays outside of Belgium.

The beer’s fascinating evolution, and the subsequent success of this re-engineered Duvel, came to define a whole new style—Belgian Golden Strong Ale—marrying the fermentation flavours and malt character of a Belgian Tripel with the clean, dry, drinkability of a German Pilsner. Before Duvel, there was no such thing as Belgian Golden Strong Ale.

Duvel continued to grow in reputation throughout the 1970s and 1980s but it was a fourth generation of Moortgat family brewers that raised it to the elevated global status it enjoys today. Current CEO Michel Moortgat stepped into the business in September 1991, aged just 24 years old. A few months later, Michel’s father died after a battle with bone cancer (his mother had already passed away when he was just seven years old). Then the following year, his uncle Emile, then-CEO, passed away too.

Michel Moortgat and his brothers Bernard and Philippe inherited a large stake in the Moortgat brewery alongside other family shareholders, but most of their cousins did not share the vision of Michel and his brothers for the future of the brewery. The cousins secured an offer from Heineken to buy their shares. But the deal would only proceed if Michel, Bernard, and Philippe would sell theirs too.

Instead, Michel Moortgat and his brothers bought the shares of their cousins, taking on huge debt to finance the buy-out, with a large part of the value of the company being used as collateral. In 1998, Michel Moortgat became CEO, owning more than half the shares with his brothers. He was 31 years old. They had just saddled an otherwise financially healthy company—albeit one that was heavily reliant on just one beer, Duvel, in just one small market, Belgium—with billions of Belgian Francs worth of debt.

The experience of the Moortgat brothers is not unique in Belgium; it is representative of the difficult relationships that take place across generations of the same family in these types of breweries, often hampered by tensions around issues of ownership and ambition. In this way, Duvel, the beer, stands as an icon of the complex heritage of family brewing in Belgium. But Michel Moortgat was about to change the game. Not only would he consolidate Duvel’s reputation as an iconic beer, but under his watch, Duvel Moortgat the brewery, would become an iconic company.

III. Diversification

When the fourth generation of the Moortgat family—brothers Michel, Bernard, and Philippe—took over in the 1990s, business turnover of Duvel Moortgat was in the region of €30 million. Fast forward thirty years and the most recently available figures for the 2019 financial year show that Duvel Moortgat recorded a consolidated turnover of €501 million, employing over 2,000 people, and brewing 2.2 million hectolitres of beer in the process. Duvel is now exported to over 50 countries all around the world; its main export markets are the United States, the Netherlands, France, and the United Kingdom.

Much of this growth is based on the diversification of their beer portfolio, including the purchase of a clutch of other breweries—in Belgium, Europe, and the USA—and an ambitious international approach. Duvel Moortgat no longer relies on Duvel for their survival. Despite this growth, they’ve successfully maintained the short chain-of-command and open-door policies of a Belgian family brewery which allow for flexibility and fast decision-making in response to changing trends.

Michel Moortgat is an astute businessman. He floated Duvel Moortgat on the Brussels Euronext Stock Exchange in 1999 to raise funds for the fourth generation’s takeover and investments and then delisted it in 2012 when it was in a very healthy financial position to become a private family company again. It was a gamble that paid off big time.

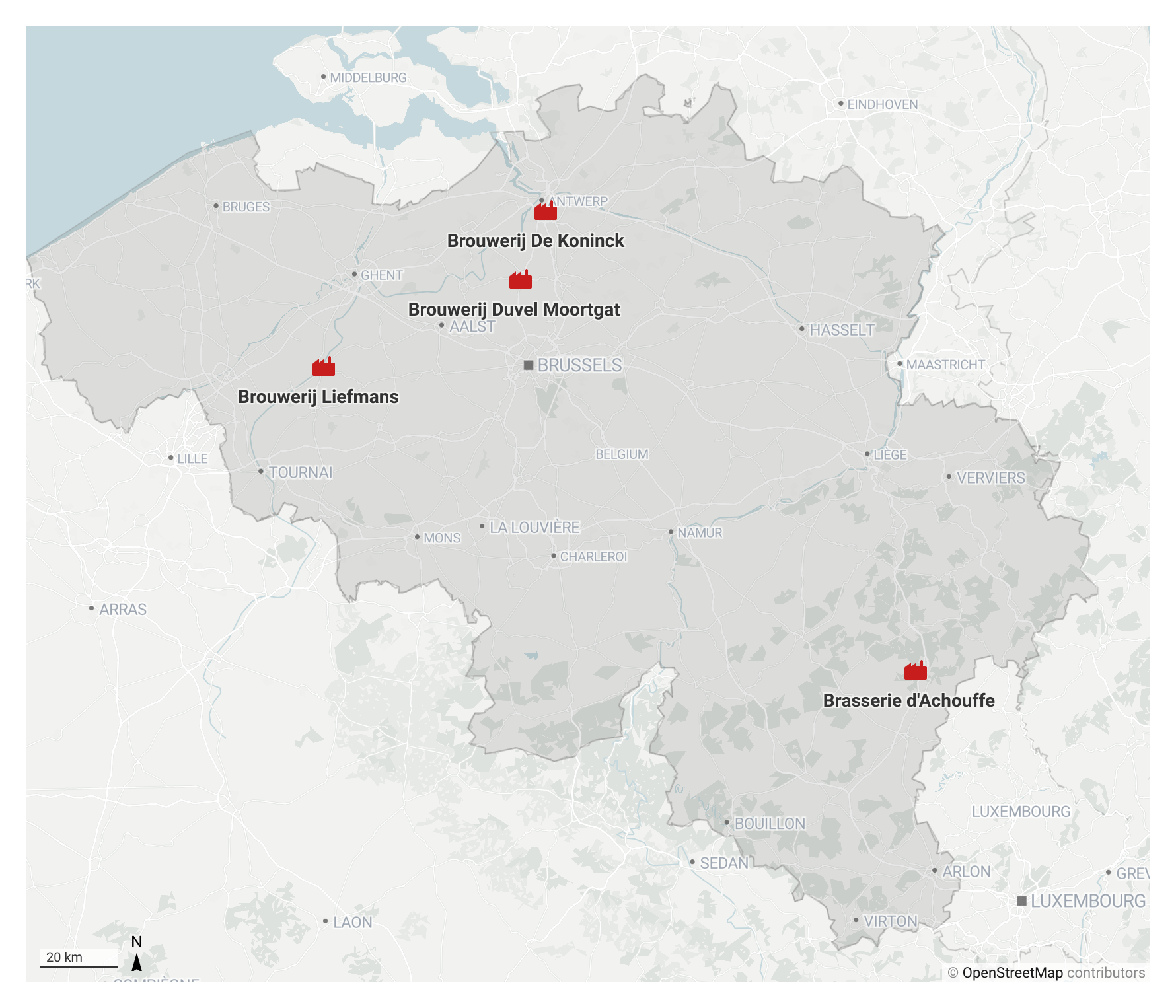

Duvel Moortgat’s purchases of other Belgian breweries—Achouffe with its quirky gnome branding and characterful ales in 2006; Liefmans in 2008, the brewery bankrupt but still respected for its mixed fermentation heritage; and De Koninck in 2010 as the producer of Antwerp’s undisputed city beer, the Bolleke—have not only added flavour profiles to their portfolio, but unlike other brewery buy-outs their purchases have largely been regarded as preserving, and in some cases, saving, the legacy of those breweries. It’s also made the company less susceptible to market changes.

Duvel Moortgat has also stretched out its arms internationally. In 2001, to secure a base for growth in Central Europe, Duvel Moortgat bought a 50% share of Czech brewery Bernard. In 2015, the brewery joined forces with Brouwerij ‘t Ij of Amsterdam in what both described as a “partnership”. In 2017, they purchased a 35% stake in Italian brewery Birrificio del Ducato, and in 2018 took a majority stake in east London-based fermented-tea brand, JARR Kombucha.

Most notable has been Duvel Moortgat’s purchase of three breweries in the United States, each with its own personality: Ommegang near Cooperstown, New York, with its Belgian ethos (January 2003); Boulevard in Kansas City, Missouri, with its “Heart of America” Midwestern values (January 2014); and Firestone Walker in California, with all of its West Coast cool (July 2015).

The company enjoys a growing popularity with a full spectrum of drinkers. Duvel, the beer, has won a plethora of awards throughout the years, including a Gold Medal in 2018 at the Brussels Beer Challenge in the category “Pale & Amber Ale: Strong Blonde / Golden Ale”. The company has also garnered the respect of the nation’s business leaders. In 2010, Michel Moortgat was named by Belgium’s Trends Magazine as Business Manager of the Year. In 2018, Duvel Moortgat finished in the Top 3 of an annual reputational survey of Belgian companies, behind national supermarket Colruyt and Lotus Bakeries, and ahead of Brussels Airlines, B-Post, Telenet, and the National Lottery. In 2019, Duvel Moortgat were awarded the prestigious Family Business Award of Excellence® by Ernst & Young, a multinational professional services network.

In a way, Michel Moortgat’s diversification—in essence turning away from a reliance on Duvel as their most famous product—has led to Duvel becoming even more iconic. Because of Duvel Moortgat’s richer and more wide-reaching portfolio, Duvel is now known by more people around the world than ever, penetrating markets they couldn’t before. As the Duvel Moortgat stable of brands grows, the Duvel brewers have been able to take on board knowhow from highly qualified brewers in other countries and from different types of facilities. And the financial success of Duvel Moortgat’s other brands has allowed Michel Moortgat to invest more heavily in assuring Duvel’s technical quality, perpetuating its status as an icon of Belgian beer.

IV. Composition

While the production of the beer Duvel involves a whole range of complex processes, there are three differentiating characteristics in its construction which have most contributed to its iconic status. The first is the fact that it is extremely pale. The second is its fermentation profile, both in performance and in flavour. And the third is its very high carbonation.

First, its paleness. It’s often said that people drink with their eyes, and a very light, pale blonde colour has long attracted beer drinkers. Pale Lager is, for example, the most consumed beer style in the world. Part of Duvel’s iconic character, then, is that it is an ale with the enticing appearance of a Pale Lager. Duvel clocks in at a very pale 6 EBC (3 SRM) on beer’s colour scale, or “sometimes lower,” according to Dimitri Staelens.

Duvel is brewed with just one malt—pilsner malt. The other fermentable is liquid dextrose, a simple sugar that is virtually completely fermentable. The malt contributes the biscuity notes and the pale blonde colour, while the sugar boosts the ABV while keeping the body thin. While brewers at Duvel Moortgat do not reveal the exact ratio of sugar to malt, Staelens says that it can be easily discovered by anyone with good density measurement equipment. “In order to make a heavy bill, it’s not a small portion [of sugar],” says Staelens.

One of the most important ways the brewers at Duvel ensure the colour is very pale is by minimising what is called “thermal load”. Heat darkens beer. Keeping your wort at high temperatures for a second longer than required will result in a darker beer than you might otherwise obtain.

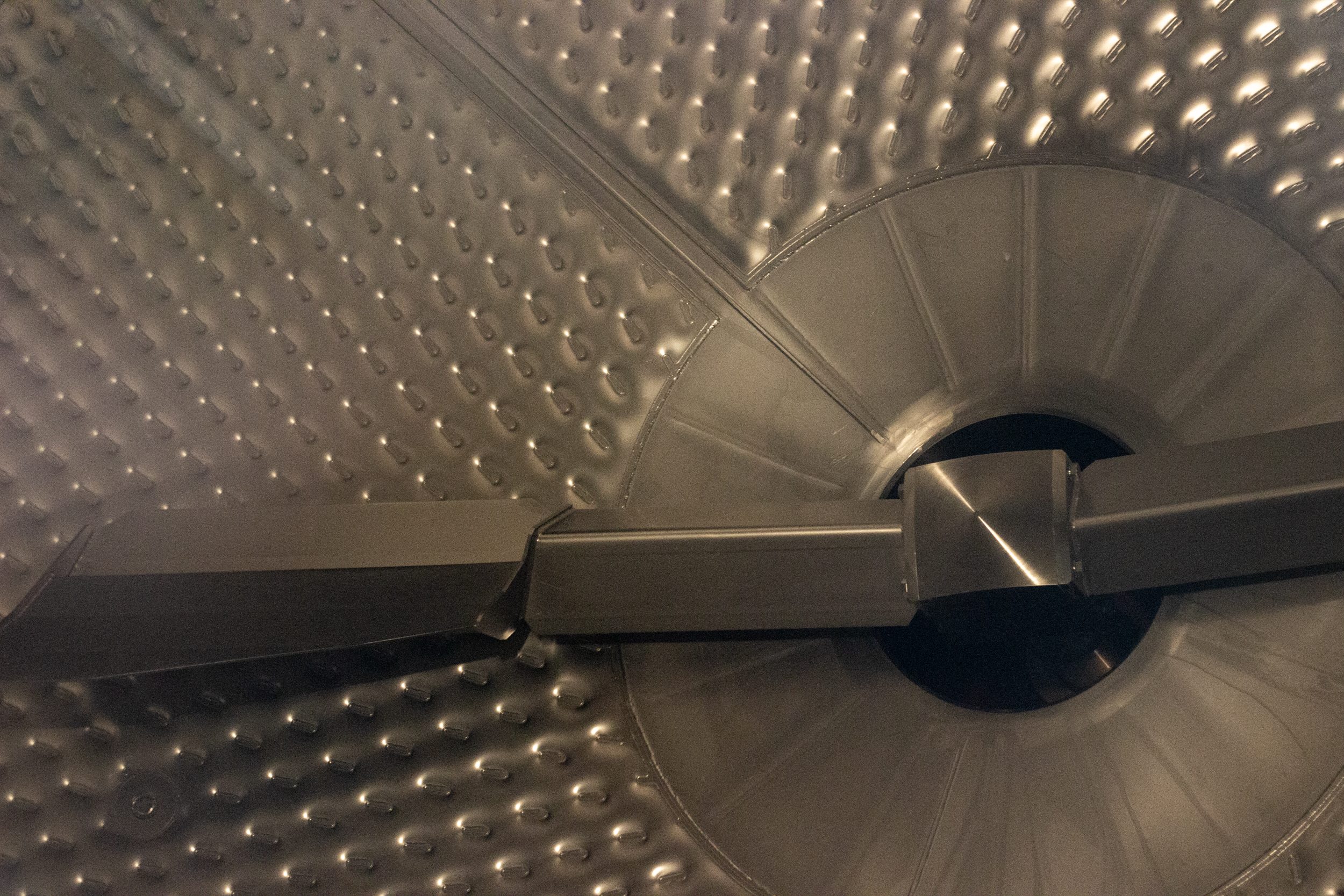

There are several examples of Duvel’s obsession with minimising thermal load. Their mash tuns have been manufactured with Steinecker’s “Shakesbeer” technology, with “pillow plates” and “vibration units”. These help distribute steam powered heat to wort much faster, reducing the time it takes to reach target temperatures, and they deliver homogenous mixing during mashing, preventing maillard reactions such as caramelisation which darken the wort. In addition, Duvel Moortgat do not need a mixing arm in their mash tuns, further minimising the risk of another cause of darkened beer: dissolved oxygen.

Notable is their use throughout production of multiple centrifuges, devices which separate solids from liquid by centrifugal force. Duvel Moortgat does not have a whirlpool, a common vessel in breweries in which wort is spun at rapid velocity to separate hop pellets and trub from the wort. Instead, they pull wort through two centrifuges—“the biggest wort centrifuges in the world,” according to Staelens—dramatically shortening the cooling time of the wort. This greatly cuts the time it sits at higher temperatures and further reduces the thermal load.

There are, of course, other techniques to ensure a very pale beer. Dimitri Staelens says that one of his most important regular quality meetings is with the three or four companies who supply pilsner malt to Duvel’s tight specifications. In addition, the brewers don’t add liquid sugar to the boil, a process which would also darken beer, but rather it is dosed inline post-boil.

The second iconic characteristic of Duvel is its fermentation profile. Outside of stronger Geuzes and Saisons, Duvel is one of the driest beers in its alcohol range in Belgium. The original gravity target is around 16.9°P and it generally finishes in the region of 1.2°P (“°P” or “Degrees Plato” quantifies the concentration of sugars in wort as a percentage by weight). The yeast eats deep. This dryness is a major part of what makes the beer so drinkable and so unique.

The flavours created by this deep fermentation are perhaps not as pronounced as you might expect from a Belgian ale, often known for their marked fruitiness and spiciness. In his time as Sommelier at Duvel Moortgat, Nicolas Soenen would often describe Duvel’s yeast profile as “neutral” or “pure”. In his recent discussions with Doug Piper on a Gourmet Brewing webinar, Duvel Moortgat brewing engineer Sven De Kleermaeker also described it as “pure”. Sam De Belder, the Site Manager for Duvel Moortgat in Breendonk uses the word “clean”. Dimitri Staelens describes it as “simple but complex.”

Yeast flavours are kept in check through a rigorous set of fermentation specifications. The Duvel yeast is pitched into wort of 20°C and allowed to rise to 26°C during a four day primary fermentation. It’s at this temperature that the brewers of Duvel have found what they consider to be the optimum ester and phenol compound production. Unlike other breweries who maintain fermentation temperatures by cooling their tanks with glycol or water of one low temperature, Duvel Moortgat employs a “Delta T” approach where the coolant is never more than 10°C different to the fermentation temperature. “[W]e control stress level on the yeast and do not let it ferment in a too rapid time because it will give a different flavour and aroma profile,” says Site Manager at the Breendonk facility Sam De Belder.

Once fermentation is completed, usually after four days, the beer is cooled to -2°C for a maturation or cold conditioning of 20 days, before running a gambit of three centrifuges which remove particles and haze of various sizes. After priming, it referments in the bottle for two weeks in one of Duvel’s four large warm chambers, each 50 metres long, and then undergoes a 6 week cold conditioning in the bottle before being released for sale. The whole process from mash-in to sale takes around 90 days, a timeframe very few top-fermented beers in Belgium enjoy, and one eulogised in that marketing campaign video with Belgian musicians Paternoster and Daan. It would be possible to produce Duvel in a shorter time-frame, perhaps by shortening the cold conditioning times in the lagering tank or after refermentation in the bottle, but such short-cuts would likely be detrimental to the beer’s quality as well as to its reputation.

The third iconic element of Duvel is its extremely high carbonation. It is saturated to 8.5 grams per litre of carbon dioxide (4.3 volumes CO2). That’s more than twice the level of many English Ales. Such a high carbonation level accentuates carbonic bite, delivers the visual spectacle of huge foam, and ensures the beer is refreshing and champagne-esque. In most of its adverts, including the 90 days film, there are close-up shots of Duvel’s swirling bubbles. Duvel is force-carbonated to around 5 g/l CO2 (2.55 volumes) before fresh yeast and sugar is added to exacting lab measurements for refermentation in the bottle. The result is a beer that has influenced Belgian brewing profoundly.

V. Cost

Icons inspire others. Pretenders to Duvel’s iconic status abound. But few have been able to replicate Duvel’s incredible commercial success.

Some Belgian Golden Strong Ales have been around for decades, such as Delirium Tremens from Brouwerij Huyghe (1988), Sloeber from Brouwerij Roman (1983), Satan Gold from Brouwerij De Block (1986), and Hapkin, originally brewed by Brouwerij Louwaege, but produced by Alken-Maes since 2002.

More recent competitors include Omer Traditional Blond from Brouwerij Omer Vander Ghinste (2008) and Keizer Karel Ommegang from Brouwerij Haacht (2012). In 2020, AB Inbev released a Belgian Golden Strong Ale called Victoria (8.5% ABV), the name reminiscent of Duvel’s original name, Victory Ale. The label of AB Inbev’s Victoria shows an angel holding the devil to the ground, an unsubtle visual AB Inbev says comes from the story of Archangel Saint Michael’s triumph over the devil. Those that attempt to take Duvel’s place as the most successful Belgian Golden Strong Ale on the market are sometimes referred to by Belgian beer enthusiasts as “Duvel Killers”. Many have tried. None have succeeded.

But Duvel Moortgat’s commercial prowess and critical acclaim, as well as its growing international ambition, have sparked tensions with other Belgian breweries.

In 2015, just after Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck released Filou, their new Belgian Golden Strong Ale of 8.5% ABV—packaged in the same steinie bottles used by Duvel Moorgat and with similar red lettering on a white label—Duvel Moortgat introduced a claim against Van Honsebrouck in the Commercial Court of Brussels. They argued that Filou was freeriding on the look and feel of Duvel and demanded that production and advertising of Filou should cease. The Court eventually rejected all of Duvel Moortgat’s claims, concluding that the average consumer would be able to easily tell the two beers apart. Perhaps the Court felt Duvel was too iconic to be confused with another beer.

International expansion has also brought with it its own controversies. Earlier this year, one of Duvel Moortgat’s American breweries—Boulevard Brewing Company of Kansas City, Missouri—was the subject of allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination. A number of Boulevard’s senior staff have resigned. Feedback on social media has been vitriolic. Employees are thought to be considering a mass walkout to protest. Duvel’s rapid growth and phenomenal success has meant they are now accountable for a lot of people. Ambition and diversification can present as many challenges as it does opportunities.

An icon is a representative symbol of something, a person or thing worthy of veneration. It’s a term often overused, but not in the case of Duvel.

The beer has been responsible for spawning a whole new style of beer—the Belgian Golden Strong Ale—and is revered for its extremely pale colour, its fermentation flavours and its dryness, its carbonation, its balance, and its drinkability. It’s also iconic because its origin story symbolises Belgium’s rich brewing heritage and hints at the beer culture Belgium has shared for decades with other countries like the UK and Germany. The characters of the beer’s past and the place of its production provide a reminder of the horrors inflicted on Belgium by war, but also celebrate the advanced technical ability of the country’s brewers and scientists. It’s an example of the internal tensions that a family dynamic can place on Belgian breweries, as well as the strengths of such longevity. Its commercial success has allowed its producer to grow and diversify, in turn ensuring continued investment in its quality. And it has inspired a wave of new beers in its mould, both at home and around the world, in some cases leading to conflict with others, as well as, in some instances, undesirable human consequences.

But those trying to replicate Duvel’s impact should heed the words of their brewers. “If it’s just a simple trial to copy and paste, I would say that sometimes they are worse off,” says Quality Director Dimitri Staelens. “I think there are some versions on the market which give a little twist, and for me, these are the most interesting ones.”

It’s all there in the first lines of the Daan song featured in Duvel Moortgat’s 90 days promotional video: “If you try to be an icon / Then the icon becomes you / If you try to be a model / It’ll catwalk over you / If you try to walk in straight shoes / Then these shoes will bend you too / If you try to be a kid again / The kid will kidnap you.”

*