First released in 2008, OMER Traditional Blond has transformed the fortunes of Brouwerij Omer Vander Ghinste. What was once a regional Lager producer is now a nationally recognised producer of “specialty beer”. The story of the creation of the beer is one of generational transition. It’s the story of family identity. And it’s the story of a prince hesitant to take on a crown made heavy by the weight of tradition.

Words by Breandán Kearney

Photography by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Oisín Kearney

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Game Changers” series of stories.

I.

Dillenger

When the other business students in the class of 1989 found out that 26-year-old Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste’s father owned a Belgian brewery, they decided that brewing would be the perfect commercial activity for their group project.

The prestigious Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Chicago, USA—ranked #1 business school in the world by The Economist—was well-known for pioneering projects in the education of business leaders. The students’ fictional brewery would be called “Dillenger” after the famous Chicago gangster, and the Belgian in the group, Omer-Jean—just like his father back in Belgium—would be the CEO of the brewery.

When Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste went to Chicago’s Northwestern University back in 1989, he left behind the family brewery in which he had grown up.

Omer-Jean’s father had owned only 50% of Brouwerij Bockor, the other half controlled by his father’s brother, Pierre Vander Ghinste. Uncle Pierre had three children of his own and there had been uncertainty about the future ownership of the business.“We were a family where we didn’t talk,” says Omer-Jean. “About the future, or money, or arrangements.”

In 1984, just as Omer-Jean was finishing a Bachelor of Law at the University of Antwerp and embarking on a Masters of Law at the University of Leuven, Pierre Vander Ghinste decided, for reasons unknown, to retire from the family brewery. Pierre sold all of his shares to his brother, Omer-Jean’s father.

“Law wasn’t the best preparation to run a brewery,” says Omer-Jean, sensing an opportunity. Using his father’s contacts in beer distributorships and global malting companies, he began securing traineeships in breweries in Belgium and around the world.

After a period working for the independent Artois brewery in Leuven in 1985, Omer-Jean embarked on a 7 week traineeship at the South African Olson’s Kay brewery in Apartheid-era Cape Town. He secured a 5 week internship in 1986 at the Panamese brewery, Cerverseria Nationale. When he returned to Belgium later that year, Omer-Jean worked at Jupille in the south of Belgium, the brewery responsible for what would become Belgium’s most ubiquitous lager, Jupiler.

In 1988 Omer-Jean served 12 months of obligatory military service in Belgium where he had been assigned to a relatively straightforward role at the Belgian Department of Transportation. During the service, he spent most of his time applying for business courses around the world. There was a lot of history associated with his father’s brewery, and there would be a lot of pressure on his shoulders should he come on board. So instead of joining his father in the family business after military service, he left immediately for the United States of America.

“I was the expert,” said Omer-Jean, recalling fondly the persuasions of his international classmates in the American school to commit to a brewery business project. Together the group visited American bars where they would order pitchers of American Lite Lager Budweiser and visit a small brewpub which had just opened in Chicago called Goose Island.

When the business plan for their fictional brewery was submitted, the group received praise for its originality and creativity. The Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste who had started the course had been unsure of his future. But the Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste who returned to Belgium in 1990, with his MBA at The Kellogg School of Management, was full of confidence.

Self-admittedly “bumped up by the MBA mentality,” Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste now set his sights on bigger targets. His father’s brewery was small, brewing a Lager and selling it regionally through a network of pubs the family had inherited over the years. Omer-Jean wanted to be part of something bigger.

In August of 1990, Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste started working as a sales and marketing executive in the Belgian offices of Coca Cola.

II.

130 Years

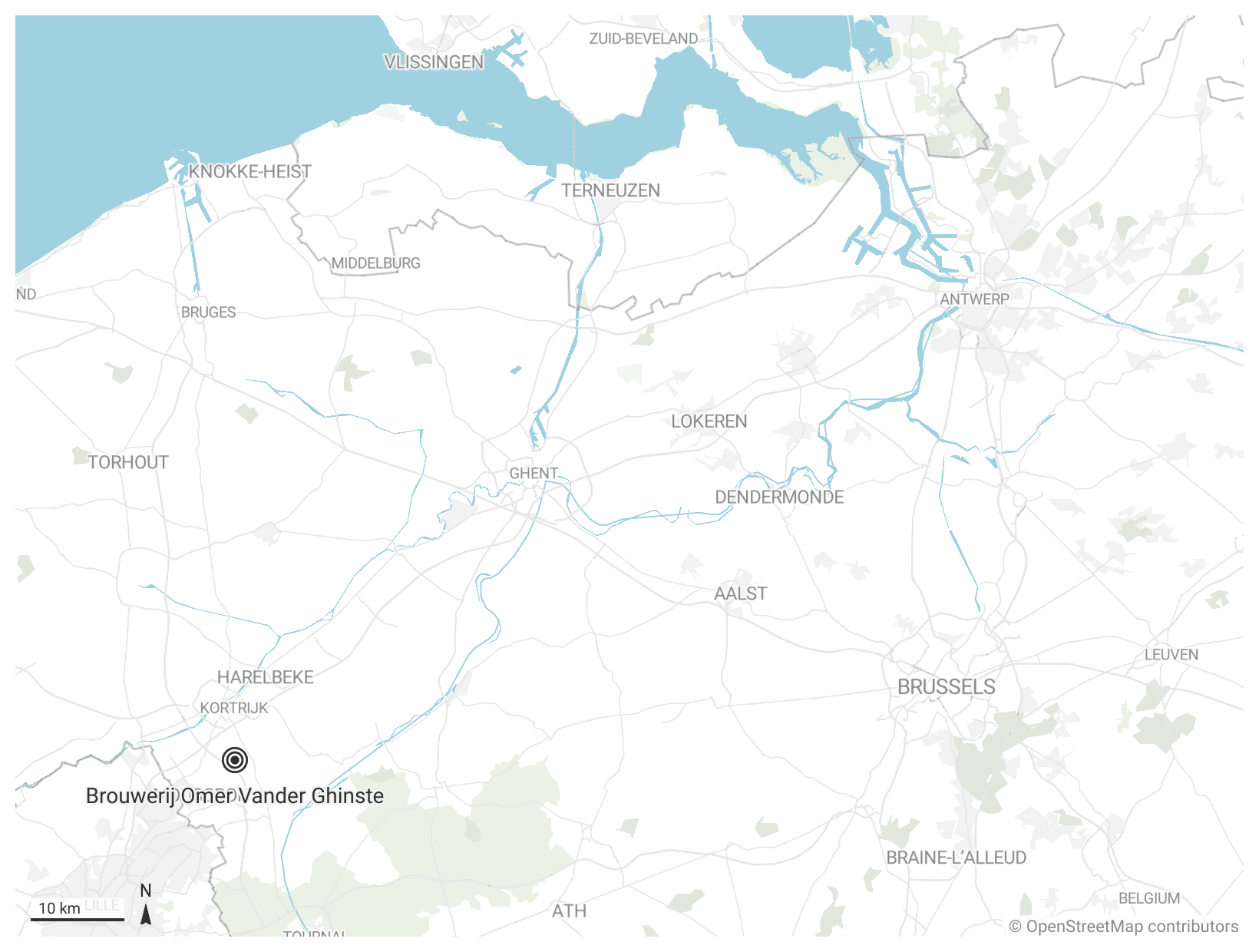

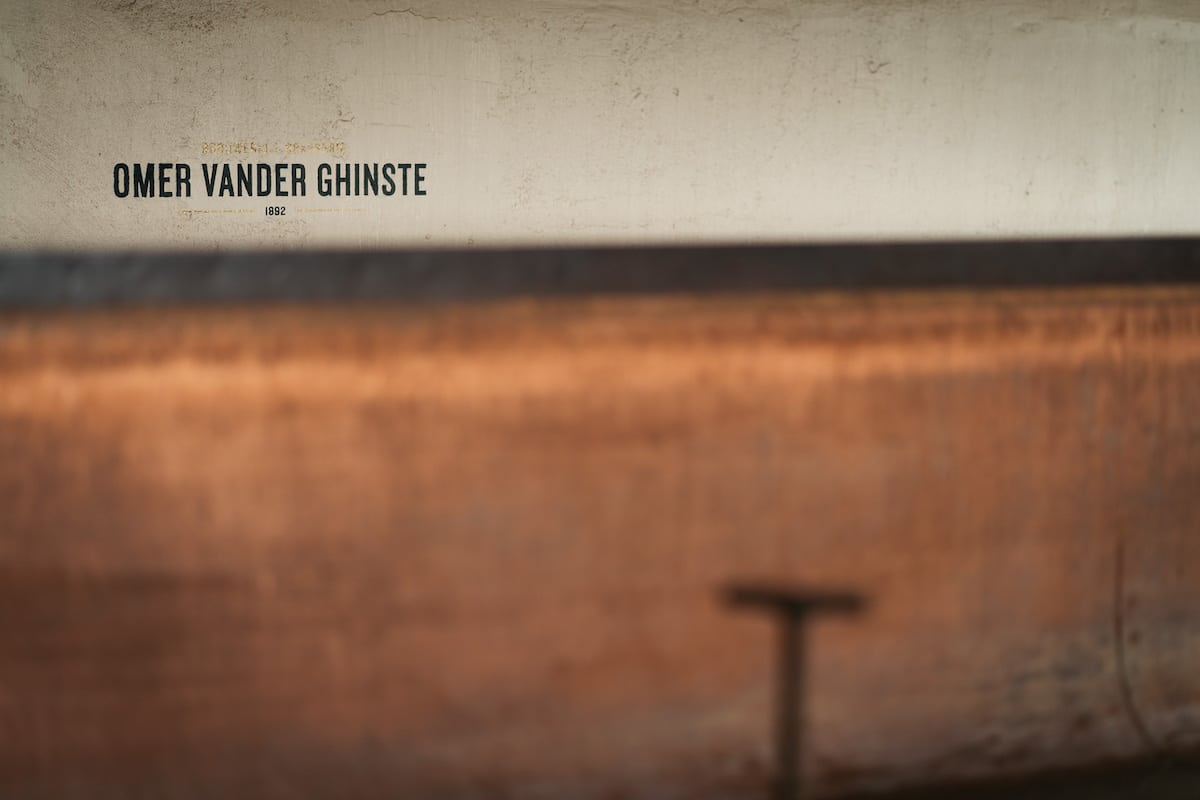

In September just past, in the small village of Bellegem in West Flanders, now 58 year-old Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste presided over the 130th anniversary of his family brewery, Brouwerij Omer Vander Ghinste, known as Brouwerij Bockor until 2014 when Omer-Jean changed its name back to the family’s name.

The story of the brewery is a good example of how regional family breweries in Belgium operate: their strong focus on local café properties as a reliable distribution network for their beers; their flexibility in switching from Lager to specialty ales as the market changed over generations; and their connection to the villages and families embedded in their very existence.

Brouwerij Omer Vander Ghinste’s beers include regional specialties such as the Vander Ghinste Roodbruin and the Cuvée des Jacobins mixed fermentation beers; European Lagers such as Bockor Pils and Blauw Export; and a range of classic Belgian ales, including Bellegems Wit, Lefort Tripel, and their latest brett-conditioned release, Brut Nature. But it’s a Strong Blonde Ale of 8% ABV that the brewery released in 2008—OMER Traditional Blond—which has transformed the fortunes of the brewery from a regional Lager producer to a nationally recognised producer of “specialty beer”.

OMER Traditional Blond is a highly carbonated, fruity, and relatively dry ale with a pleasant but subtle bitterness. The beer not only sheds light on Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste’s vision to double-down on the family heritage of the brewery, but communicates more generally the complex story of generational transition in Belgian family brewing. So just how do you go about creating a beer brand that reflects the legacy of your family?

III.

Stained Glass

Omer Vander Ghinste—Omer-Jean’s great-grandfather—started their family brewery in 1892, producing small quantities of several beers. To survive—as would have been common at the time—the first Omer travelled around the village with a horse and a small wooden cart delivering his beer to pubs and private customers. On the side of the cart was a sign that read “Bieren Omer Vander Ghinste”: “Beers of Omer Vander Ghinste.”

In order to gain a foothold in the village commercially, Omer Vander Ghinste purchased a small cafe on Bellegem’s Kwabrugstraat, investing in stained glass windows with blue, white, and black art deco lettering which spelled out the words “Bieren Omer Vander Ghinste”.

Omer Vander Ghinste was a country boy from the village of Bellegem but he fell in love and married a city girl, Marguerite Vandamme, whose grandfather Felix Verscheure owned Brasserie Le Fort in Kortrijk. When Verscheure died, Le Fort passed directly into the hands of his granddaughter Marguerite, and together, Omer Vander Ghinste and Marguerite Vandamme moved all production to Bellegem, using the portfolio of Le Fort cafés to grow volume. These cafés soon showcased their own windows of stained glass and art deco lettering, proudly claiming that the beers poured inside were those of Omer Vander Ghinste.

Designing and installing stained glass windows was an expensive enterprise, so when a son was born to Omer Vander Ghinste and Marguerite Vandamme in 1901, it was decided that rather than change the markings on all the windows of all the cafés, or constructing new ones to reflect the new name, the child on its way, should it be a boy, would be given the same name as his father. That way, when the child grew up and inevitably took over the business, the stained glass windows could be preserved.

Omer’s son, then, was named Omer-Remi Vander Ghinste, the double-barrel second name extension established to more easily differentiate between father and son.

IV.

Bockor

In the 1920s, a global financial crisis began to squeeze brewery activities across Belgium and local consumers began moving away from their regional specialties—Saison, Witbier, Oud Bruin, and Lambic—and opting for the influx of German-style Lagers.

Because he could see sales of his Oud Bruin struggling, Omer-Jean’s grandfather and the second Vander Ghinste to lead the brewery, Omer-Remi Vander Ghinste, considered changing career and started putting all his energies into his other great passion: motor cars.

Omer-Remi secured a license from the Ford Motor Company in the US to sell Ford cars in the region, purchasing a garage in the nearby city of Kortrijk as a base for his new activities. All he needed to do was to sell his brewery to raise funds for this car sales business. So on one day in 1929, he took a train to Leuven.

Omer-Remi Vander Ghinste was expecting a warm reception from Brouwerij Artois, perhaps from one of the Spoelberch family who were prominent shareholders of Belgium’s biggest and richest brewery, or maybe even from Albert Van Damme, the powerful and wealthy owner himself.

Instead, he was met by a low-level administrative staff member and given only a short period of time to present his proposal. Angered, Omer-Remi took the train from Leuven back to Bellegem feeling ignored and derided. He vowed to continue brewing and immediately on his return began developing the capacity of his brewery to produce bottom fermented beers at a considerable capital investment.

He did two things. The first was to invest in equipment for lagering beers, giving the brewery the opportunity to ferment beers at lower temperatures and cold condition them for longer periods. The second was to build a brewery tower, the highest part of the brewery, one which would house their coolship and stand as the tallest structure in the village of Bellegem.

Omer-Remi’s decisions saved the brewery. Over the following decades, the brewery flourished. Its first bottom fermented beer—a golden-coloured Lager originally called Ghinst Pils but renamed Bockor in 1937 (“Bock” for the German style and “Or” being the French for gold)—would become so popular that Omer-Jean’s father, Omer Vander Ghinste, invested most of the brewery’s resources into its continuous improvement and distribution when he took over in 1961.

Bockor morphed into a classic international Lager—brewed with small amounts of corn and a soft bitterness—and defined the brewery to such an extent, that in 1977, Omer-Jean’s father changed the name of the brewery from the family name (Brouwerij Omer Vander Ghinste) to one that would reflect its most important product: Brouwerij Bockor.

The naming conventions for first born sons in the Vander Ghinste family continued across the generations.

Omer-Remi’s son (Omer-Jean’s father) was called Omer. And then in 1964, along came Omer-Jean.

“You sometimes need to add one,” says Omer-Jean of the hyphenated part of his name. “Otherwise, there are three Omers coming when you call one.

V.

A New Beer

Since he had started working there in 1990, Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste had enjoyed considerable success at Coca Cola, starting out adapting the company’s American marketing campaigns for European audiences—sometimes simply by dubbing American TV spots directly into Dutch and French—and working on the launch of Coke Light in Belgium.

Soon, he was promoted to sales and marketing, and was given the responsibility of leading a sales team of 7 people in the region of Limburg in the North East of Belgium.

But the inside of a huge company was different from what Omer-Jean had expected of big business. Coca Cola didn’t belong to him. It wasn’t his. No matter how much he gave to it, it would never be a part of him.

More and more, he was thinking about a family business; about building something of his own. And more and more, he was thinking about his father. Perhaps Omer-Jean could help his father grow the reach of their flagship beer Bockor, and maybe even introduce a new beer of his own.

In the summer of 1992, Omer-Jean left Coca-Cola and started working at the brewery in Bellegem. Brouwerij Bockor had a second family member on the payroll. Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste would grow to love working with his father. They respected each other’s skill sets; Omer was an experienced brewer who had ensured Bockor always met high quality standards, and Omer-Jean came with commercial nous and new business ideas.

One year later, in 1993, Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste had a son.

He named him Omer-Géry Vander Ghinste.

VI.

The Delvauxs

For years, Bockor’s success powered the brewery, but by the mid-2000s, it was clear that the beer market in Belgium was changing. Sales of Bockor were slowing in the face of a rise in Belgian specialty beers.

Omer-Jean’s father had released a beer in 2002 called Kriek Max, a cherry beer which, despite an initially strong commercial showing, had not garnered the respect of beer enthusiasts due to its high levels of residual sweetness and its loud marketing. It was clear that the Vander Ghinste’s needed something new. The ambition was a strong beer which was highly drinkable, to meet market demand, but with an expressive yeast character that did not lean too phenolic, so that it would differentiate itself from other products in the style.

This was the backdrop for a meeting in 2007 at the brewing lab of KU Leuven between the Bockor team and the Delvauxs.

Freddy and Filip Delvaux were a father and son team of brewing specialists and consultants who had worked with a range of well-known breweries—including St Bernardus, De Koninck, La Chouffe, Westvleteren, and Westmalle—on fermentation issues, recipe formulation, and quality control issues.

Around the table opposite the Delvauxs were: the Head of Production at Bockor, Carl Alsberghe; the Quality Manager Sam Quartier; and two Vander Ghinstes, father Omer and son Omer-Jean. Work on the new beer had been ongoing for more than two years.

Keen to establish a link with the brewery’s family heritage, it was suggested that the brewery use the Bockor yeast, a lager strain of which the family brewery had grown immensely proud.

The initial samples presented by the Delvauxs had involved fermenting a higher gravity wort with the Bockor yeast at higher temperatures normally seen with Lager strains. The feeling was that this might create more pronounced esters and equip the beer with a more fruity fermentation profile. However, after tasting the results, everyone around the table decided to change approach. “The beer was not good,” says Filip Delvaux. “We decided it was not a good idea.”

Freddy Delvaux had been working for 30 years in brewing consultancy and had collected a large number of yeast strains from different breweries, isolating cultures from various bottles and other commercial sources.

The Delvauxs and the Bockor team decided to ferment the same wort from the previous tests with selected strains from the Delvaux yeast bank.

It soon became clear that there was one yeast better than the others.

At the final taste test, Omer-Jean saw that the beer in his glass was bright and golden, an ice-cream head of white foam pillowing on the top of the glass. It was bready and grainy without being heavy, a biscuit quality deriving from Loire valley malted barley. There was an underlying bitterness there, with an earthy, floral aromatic hop character deriving from the German, Czech, and Slovene varieties deployed. The carbonation was high, almost champagne-esque.

But it was the yeast that stood out most. At first it was clean but as the beer warmed, there were subtle esters ranging from pear to apricot and then to citrus. Only on the very back end was there a hint of pepper, but none of the 4vg phenolic spice that Alsberghe, Quartier, and the two Omers had been so keen to avoid.

It attenuated highly, drying the beer out and adding to drinkability. It fell outside of—or perhaps somewhere between—existing styles, boasting the light-bodied crispness of a Pilsner, the high alcohol and effervescence of a Belgian Golden Strong Ale, and a hint of a Belgian Tripel’s fermentation profile.

“This is it,” said Omer-Jean of this strong but highly drinkable ale with an expressive yeast character that he believed would bring more people to the Vander Ghinste story. “This is what we’re going to make.”

VII.

The Name

The new beer became Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste’s obsession at work at a time that his father Omer Vander Ghinste was feeling increasingly unwell, taking more of a back seat in the operational business of the brewery. Omer-Jean would make his father proud by managing a successful launch of the beer.

It was important that the name of the new beer reflected the values of the brewery as an independent family owned enterprise based for generations in the village of Bellegem.

When Omer-Jean asked what they should name the beer, his father replied that there was only one name: Omer.

While there were several beers in Belgium exhibiting the surname of the brewing family—Maes Pils, Spécial De Ryck, Stout LeRoy, Oude Geuze Boon—no major commercial beer in Belgium at that time had been branded using a first name.

While “Omer” is widely considered among Belgians to be a name of French origin, it has roots in French Flanders, part of the historical County of Flanders in present-day France. In the arrondissements of Lille, Douai, and Dunkirk, Flemings were traditionally the dominant ethnic group and a dialect of Dutch was, and in some areas still is, traditionally spoken. Less than 100 kms directly west of the village of Bellegem lies one of the most important communes in this region of Hauts-de-France, the city of Saint-Omer.

Omer-Jean took his father’s idea—that of naming the beer “Omer”—to several external marketing agencies, most of whom felt it would convey an antiquated image and lose appeal in the youth market. “The people there found it so old-fashioned,” he says. “It wasn’t well received.”

Despite the uncertainty about the name, it was agreed for commercial reasons that the new beer would have to be launched in September 2008, the date of the biggest hotel, restaurant, and café trade show in Belgium—the “Horeca Expo” in Ghent. Omer-Jean’s father Omer Vander Ghinste, if he was feeling up to it, would make a short speech there, introducing it to clients and the media, as well as attending several other events to promote the beer. Omer-Jean would be on hand to assist his father with the launch.

As 2007 progressed, however, Omer’s illness became more serious and he was diagnosed with cancer. “It was very difficult,” says Omer-Jean of seeing his father suffer. “He was in a lot of pain. A lot of physical pain.” On 5 October 2007, Omer Vander Ghinste passed away. He would never see the new beer launch to market.

With very little time to grieve, Omer-Jean was forced into a leadership role, the fourth-generation owner and manager of his family brewery. On top of the management of personnel and the supervision of all production issues, Omer-Jean was required to oversee the launch of a new beer at the brewery for the first time in 6 years. Much had been invested in the new beer. The other family breweries across Belgium were watching closely. The brewery’s future—and his father’s legacy—would depend on the success of OMER Traditional Blond.

VIII.

Tournée Générale

All of the Belgian family brewers were in attendance at Horeca Expo in Ghent during September of 2008. As the biggest hospitality event in Belgium, breweries could establish contracts for the year with distributors and café owners from all over the country and generate hundreds of potential new clients.

Brouwerij Bockor’s booth included an image of the stained glass windows of the brewery’s past, with the new release, OMER Traditional Blond, centre stage. It was the first time that anyone not involved in its development could try the beer. Omer-Jean was nervous. His name was on the bottle. His name was on the glass. His name was on the line.

Despite a strong critical reception, the new beer’s launch was overshadowed by the launch of other beers at the Expo, including Hopus from Brasserie Lefebvre. Omer-Jean realised that it wasn’t just his own name front and centre. It was his father’s name; his grandfather’s name; his great-grandfather’s name. Perhaps most importantly, it was the name he had given his son. What would he be passing on to Omer-Géry Vander Ghinste?

But in the months that followed, there was some indication that this new beer was special. In 2008, it won Gold at the European Beer Star Awards in Germany in the Belgian Style Strong Ale category. And then in 2010, it won Gold at the World Beer Cup in the USA in the same category. OMER Traditional Blond was a beer of which Omer-Jean was proud. If only more people could know about it, the beer might go from respected ale in its West Flemish homeland to a household name in Belgian beer.

Around the same time, Belgian guitarist Jean Blaute and English television presenter Ray Cokes, were shooting their discovery series, Tournée Générale, about Belgian beer for national channel Eén when they drove into Bellegem with their blue and white Volkswagen campervan. It was the second series they were shooting after a successful debut in 2009 with Sputnik media, the idea being that Cokes would play the intrigued and hapless tourist, with Blaute as the proud Belgian showing off the hidden gems of his brewing culture. The show enjoyed huge viewing figures across Belgium and would go on to gain a third season.

When Blaute and Cokes meet Omer-Jean Vander Ghinste at Café De Sportwereld, the camera follows the three men—with background shots of the café’s stained glass windows and art deco lettering: “Bieren van Omer Vander Ghinste”—as they walk down Kwabrugstraat towards the entrance to the brewery. The camera pans to the brewery tower, built at the end of the 1920s to facilitate the production of pilsners, and then hones in on the group of three men in the bar and terrace inside the brewery tower. Omer-Jean pours bottles of OMER Traditional Blond.

“Did you develop this in-house,” asks Blaute. Omer-Jean talks about the assistance they had received from the father and son team, Freddy and Filip Delvaux, who had themselves been guests of Tournée Generale in its first series.

Tasting the beer, Cokes licks his lips. “Oh that’s good,” he says. “There’s a very subtle bitterness to this beer.”

“We use three different hops which give the typical soft bitterness,” says Omer-Jean.

The last line of the conversation in the programme comes from Ray Cokes. “That’s one of the loveliest blondes I’ve ever tasted,” he says.

The Brouwerij Bockor episode of Tournée Generale—episode 3 of series 2—aired on 2 February 2011. Within two weeks of it airing, Omer-Jean’s sales teams had informed him that OMER Traditional Blond was flying out the door. Within two months, all OMER Traditional Blond in stock was completely sold out. They would have to brew more and they would have to brew it immediately. The programme had not only raised the profile of the beer, but it had also disseminated the story of the brewery all over Belgium in a way that had connected with people.

IX.

Brouwtorenstraat

In recent years, OMER Traditional Blond has gone from strength to strength, powering the brewery forward and facilitating the building of a brand new brewhouse on the Kwabrugstraat in Bellegem. The Vander Ghinste’s family brewery has become so important to the village that part of the Kwabrugstraat was renamed in 2019 to “Brouwtorenstraat”—”Brew Tower Street”.

The new fully automated Steinecker brewery allows Brouwerij Vander Ghinste to brew 5 times in the space of 18 hours, increasing their annual capacity from the 90,000 hectolitres of their old 1947 brewhouse to a possible 180,000 hectolitres today. (They brewed 110,000 hectolitres in 2021, 20% of which was exported, mostly to neighbouring countries France and the Netherlands). There’s now 90 people working for Brouwerij Vander Ghinste, a far cry from Omer Vander Ghinste’s one-man horse-and-cart show of 1892. Their annual revenue in 2021 was somewhere in the region of 30 million euro. They’re expecting 15,000 visitors to the brewery in the next year.

In a press release to mark the 130th anniversary of the brewery in September 2022, Omer-Jean was quoted as saying that he had received a fantastic brewery from previous generations and that he wants to pass it on even better to the next. There are also quotes from his son, 29-year old Omer-Géry Vander Ghinste, about preserving the heritage. Omer-Géry started at the brewery in 2019 as the fifth generation of his family to work there; most likely the next Omer to lead it.

When your surname is the name of the brewery and your first name is on its most important beer, there’s a little bit of pressure on your shoulders to ensure it works, and maybe even to launch a successful new beer under your watch.

*