A philosopher based in the city of Leuven became dissatisfied with how sterilised and controlled modern culture was becoming. So he moved to a farm in Belgium’s Hageland, and together with his brother, began producing beer, wine, and cider, fermenting everything with indigenous yeast and bacteria. What would happen when things went wild?

Words by Breandán Kearney

Photos by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

Tom Jacobs would not look out of place in the movie franchises of Indiana Jones, or Crocodile Dundee, or even The Broken Circle Breakdown.

Despite his short frame, he has presence. His soft-brimmed grey Fedora hat, creased with teardrop crown and decorated with a sweatband of pheasant feathers, covers a mop of long brown hair that reaches almost down to his shoulders. When Jacobs first began homebrewing, he hadn’t cut his hair for fifteen years.

Those who have had the pleasure of Tom’s company for at least the time it takes to drink a beer will have heard him tell the Old Testament story of Samson, a hero whose God-like power derived from his hair. “I will cut my hair some day,” said Jacobs. “But not just now.”

On the first floor of his small brewery building right beside his house in the village of Kortenaken is another reference to the story of Samson. Tom has built a roof over his coolship, a shallow cooling vessel which facilitates the inoculation of wort with the microbiology of the farm’s environment.

At the centre of the coolship roof—a wooden frame of untreated oak filled out by grape pruning—is the skull of one of the farm’s dead lambs, dug up by Tom from its grave behind his house. It is a symbol inspired by the story of Samson, who used the skull of a donkey to kill a thousand of his enemies. After the massacre, Samson used it as a receptacle for water to parch his thirst. “The skull is a symbol of both death and life,” says Tom.

Together with his brother Wim, Tom Jacobs produces beer, wine, and cider under the name Antidoot Wilde Fermenten. Brewing takes place in a building right beside the house in the village of Kortenaken where Tom lives with his wife Kristien Justaert, and his two daughters Juno and Danse.

In February 2019, just a few weeks after releasing their very first commercial beer, Antidoot were awarded the title of the Best Brewery in Belgium for that year by the organisers of Belgium’s Beer Awards Digital Festival. The following year, in February 2020, the same awards organisation crowned Tom Jacobs Belgium’s Beer Person of the Year. Last month, Ratebeer named Antidoot as one of the Best Breweries in the World in the category of “Sour or Wild-Flavoured beer”.

Much of Antidoot’s brand imagery is based on the philosophy of Alchemy, a practice which involves transformation based on finding a new and proper balance between things. Antidoot’s story has been rooted in the Jacobs brothers’ quest to find their own sense of balance: between control and nature; between openness and exclusivity; and between life and death.

In the late 2000s, Tom Jacobs was living in the centre of Leuven and teaching philosophy and ethics at the UCLL Hogeschool to groups of nurses, chemists, and biomedical lab scientists. His journey to and from work was dominated by concrete surfaces and by PVC advertising billboards. Air conditioning vents hummed and regulated and cleansed. Lunches in the city were often processed, mostly tasting insipid and bland. Work seemed to be assigned for no reason other than to ensure that there was work to be done, with immediate deadlines and stressful working environments.

The syllabus of modern philosophy he was teaching focused on thought experiments and existential questions, a virtual element outside the physical realm. René Descartes: “I think, therefore I am.” Tom was growing tired of what he describes as “a modern philosophy all about thought.” People talked in the city, but often they didn’t act. He longed for something tangible, something carnal, something real. “I was looking for embodiment,” he says.

During his classes, he would produce a copy of “The Pasteurization of France”, by Bruno Latour, a resource he used to discuss the concept of “purity”. The pasteurisation in the title of the book is a reference to the process in food production of killing certain living organisms with heat to give a more controlled, stable product. “As a society and modern culture,” he would ask his students, “Why are we so obsessed with blank slates and artificial design? Why do we want to control everything?” He wasn’t sure that his students truly considered those questions, nevermind tried to answer them.

In 2009, Tom’s wife Kristien became pregnant just as a property in the village of Kortenaken became available to buy, a family house and patch of land in the traditional farming region of the Hageland in Flemish Brabant. It was more than just an opportunity to live an idealised life in the country. It was their chance for the embodiment he was looking, to find a new balance, to reject the pasteurisation of city existence. Just a few months after moving into their new farm home, Kristien gave birth to their daughter Juno. In Kortenaken, the young family grew their own vegetables, farmed much of the meat they would consume, and tried to live a more balanced life. As part of this, they started creating their own wine, cider, and beer.

Tom was becoming more and more passionate about fermentation. It was so different to pasteurisation. Rather than killing the wild with a view to making something safer, it meant letting bacteria and yeast break down a substance and create something new. For his fermentation projects, Tom enlisted the help of his brother Wim, a gastroenterologist based in the Jessa hospital in Hasselt. Wim Jacobs had two kids of his own—Roos and Wannes. Becoming parents had forced the brothers to think more about their futures and the things they wanted to do in their lives, and so in the summer of 2011, the Jacobs brothers started homebrewing together.

“Classical thought establishes a hierarchy where God stands above man, and man above woman and nature,” explains Tom. “Alchemy is about keeping two sides together. It’s about a natural balance. Light and darkness. The sun and the moon. Life and death.” The Jacobs brothers had no idea just how significant beer would become in the following years in their struggle to find that balance.

One element the Jacobs brothers were keen to embody in their fermentations was a sense of terroir, a unique environmental context for their beers. They experimented with natural fermentations, agreeing never to add genetically engineered “pure-culture” yeast strains. These commercial “pure” yeasts, controlled and stable, were used by thousands of brewers across Europe. Modern brewers seemed to sterilise everything, killing to limit the influence of terroir.

The attempts of the Jacobs brothers to harness the flavour profile of their environment in homebrew between 2011 and 2017 delivered what they described as “mixed results”. Due to the technical challenges of its production, there were few people in the wild beer scene in Belgium they could ask for advice and fewer that were open to advising. The world of Lambic is a political quagmire. The membership body created to protect the style and tradition of Lambic has been bogged down in disagreement in recent years, mostly on issues related to dispense, naming conventions, and new market entrants, resulting in the bleeding of members and a heightened tension between its producers. Lambic producers are not known for their openness.

Kortenaken is located in the Hageland, a region in the eastern part of the Province of Flemish Brabant between the cities of Aarschot, Leuven, Tienen, and Diest. The “Haag” in Hageland is often mistaken to be the Dutch word for “Hedge”, but the region is actually named after an old Dutch word meaning “dense forest or undergrowth”. Because of its fertile soil, the south of Hageland is known historically for its wheat cultivation. Just 23 kilometres south of Kortenaken lies Hoegaarden, a village associated with both saving Belgian wheat beer and spawning the style’s most famous commercial brand.

Tom and Wim did not ignore that legacy. In every single Antidoot brew, they use at least 35% of raw wheat from the region. Raw wheat contributes all the soft, crisp flavours that malted wheat is known for, but delivers none of its sweet, full bodied qualities. Raw wheat is also high in complex proteins, more advantageous as food for diverse microbiology during longer fermentations. The Jacobs brothers sourced the wheat directly from local farmers, stuffing as much raw wheat into their cars as would fit on each journey.

Tom secured aged hops for spontaneous fermentation from Poperinge organic hop grower Joris Cambie. He also bought hops from Benedikte Coutigny of the Hoppecruyt farm in Proven. One hop variety was Groene Bel, a classic Aalst bittering variety which was popular amongst Belgian brewers in the 19th century. Another was Record, a pleasant fruity aromatic variety originally from the Pajottenland. So that they could produce spontaneously fermented fruit beers, Jacobs cultivated fruit behind his house and beside the brewery space, establishing grape vines, blackberry plants, and blackcurrant prunes. He had also planted trees bearing apples, apricots, and mirabelle plums.

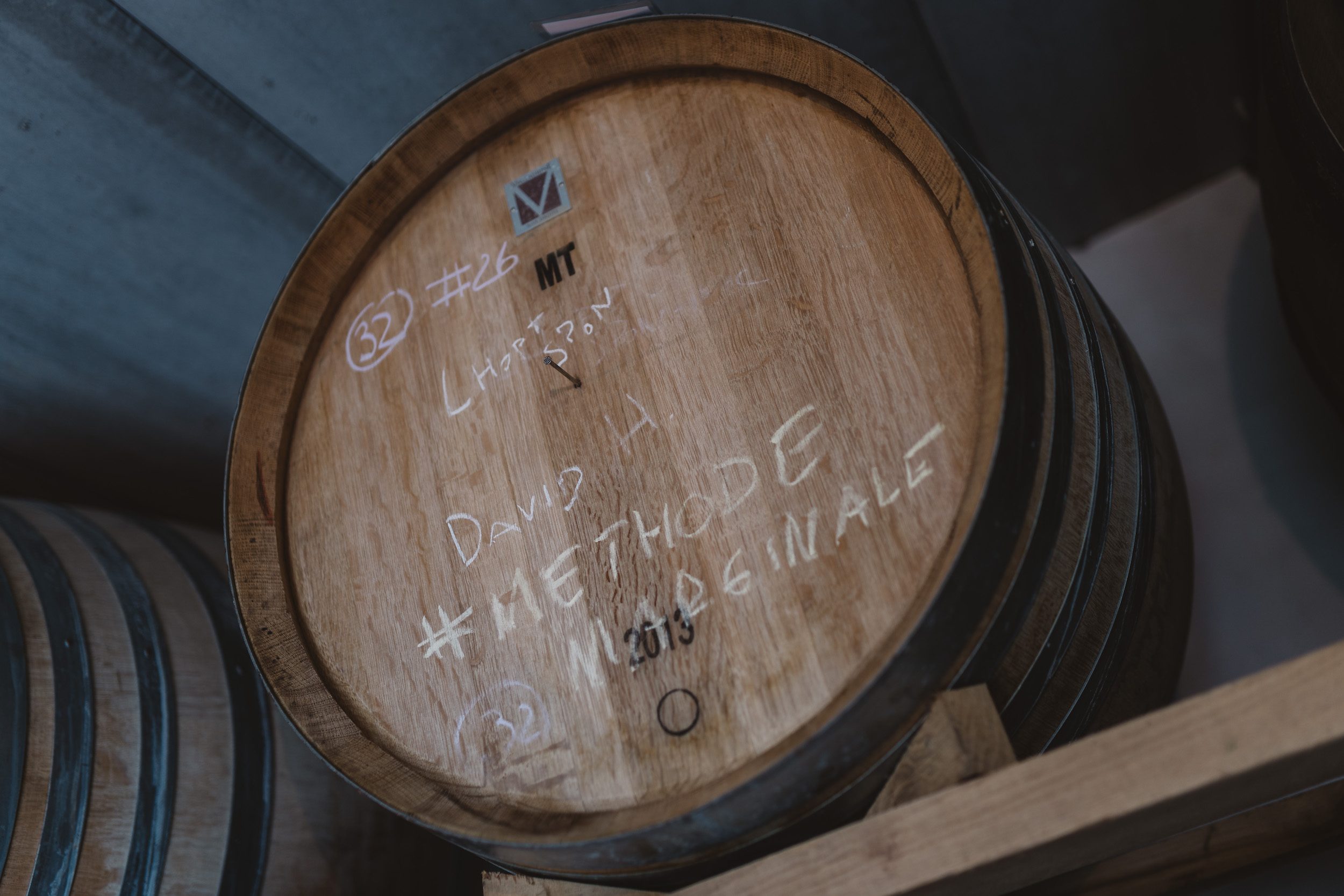

The Jacobs brothers hooked up a trailer to their car and drove 600 kilometres to Poligny, a town in the Jura department of eastern France. They visited the vineyards of natural winemaker Valentin Morel and asked if he had any barrels they could buy. A few days later, they returned to Belgium with an oak foeder, 3,000 litres in capacity, a huge wooden vat for the slow acidification of beer. The plan was to continuously feed the foeder fresh wort—“Solera style”.

The brothers believed botanicals from the farm would also help to instil a sense of place in their beer, so they began growing herbs. They opted not for classical kitchen varieties such as thyme or basil, or those commonly used in Belgian ales such as ginger or coriander, but those which Tom describes as “playful and aromatic, or esoterically bitter”: yarrow, mugwort, wormwood, and archangelica. The combination of herbal bitterness and lactic sourness would become a trademark of all of Antidoot’s beers. “The more aged, the less bitter it becomes,” says Tom, who prefers his herbal beers young. “My favourite, wormwood, is about the most bitter herb there is. But I think it works in combination with a moderate acidity. It makes it refreshing.”

These herbal experiments involved the addition of fewer hops and presented several challenges. The lack of the preservative qualities provided by hops allowed lactic acid bacteria to flourish to undesirable levels, especially in the heat of the summer. Worse, acetic acid bacteria started to become more present, leaving some experiments tasting like vinegar, the beers completely undrinkable. On several occasions, Jacobs took beers on which he had worked for six months, sometimes a year, and poured them down the drain.

A few weeks after construction work on the brewery building had begun in 2017, a Japanese vinegar fly variety called Drosophila Suzukii—the Spotted Wing Drosophila—began attacking the soft fruit in Tom Jacobs’ Kortenaken fruit field. The fly punctured some of the berries of Tom’s trees and laid its eggs in the fruit, causing them to rot and produce vinegar. Tom’s blackberries were heavily infected, along with some of the grapes. “We had already suffered after infection by a fungal disease called Botrytis the previous year,” says Tom. “Organic fruit-growing in Flanders is not the easiest endeavour.”

Tom and Wim began wrapping nets around the vines and branches of the plants to protect the fruit, particularly the grapes, from the attention of the vinegar flies. The nets—small meshed cloths—would have to be carefully placed, one by one, over individual vines. The manual labour involved was so intense that Tom decided he had time to cover only the bigger bunches. “Because of the nets, we managed to save around 75% of the grapes,” he says.

Another major issue was the changing climate, which meant the growing season for his fruit crops started earlier each year. But late frosts were killing the early buds. Tom’s grapes, mirabelles, peaches, and apricots were all frozen. “We didn’t get any last two years,” he says. “Spring starts way too early.”

The warmer temperatures during winter were also wreaking havoc with his coolship schedule, attracting unwanted bacteria that was spoiling his beer with what he describes as “rubbery, dirty phenolics which don’t go away with time”, as well as infections of biogenic amines which can be detrimental to human health. Eventually, he decided not to brew at all if the temperatures were above 5°C. While this ensured unwanted bacteria would not be present, it created another problem: he now had fewer days in his brewing season to produce the beer he needed.

In his online research, Tom came across a facebook forum called Milk the Funk which played host to fermentation enthusiasts from around the world. There, he learned about various techniques to more effectively collect “wild captures”, the indigenous strains from his farm which he would first use to produce his barrel conditioned farmhouse Saison. Over the course of 2017, several “homebrew” bottles of the Antidoot Saison made their way into the hands of members of the Milk the Funk group. It was a dry, fruity beer with a soft lactic acidity, some spice, a herbal earthiness, and a slow-developing brettanomyces note. The unofficial release generated excitement about the two Belgian brothers and their wild fermentation project in Kortenaken.

More and more bottles of mature Antidoot homebrew made their way out of Kortenaken to a community of beer geeks around Belgium. The Jacobs brothers were invited to deliver a tasting at Carnivale Brettanomyces in the summer of 2017, an acclaimed beer festival in Amsterdam featuring Europe’s most prominent producers of wild beer, natural wine, and low intervention cider. Tom was surprised by the increased interest in Antidoot before they had officially released any beer, and with the skull of a dead lamb sitting on the table beside him, the same one which would become the centrepiece of their coolship roof in Kortenaken, he announced the plans for construction of a ten-hectolitre brewery. “We had to follow through after announcing at the festival,” says Tom. “There was no going back after that.”

In the Spring of 2019, Tom and Wim released a version of their Saison as Antidoot’s first official commercial beer. L’Or du Pré was brewed with the addition of Dandelion flowers for a floral, earthy touch. The name of the beer translates as “Gold of the Field”, a poetic nickname for the Dandelion flower in French. To mark the launch, they decided to open the brewery up to visitors during an event on Saturday 27 April 2019 which they billed as a Spring Release where they would sell bottles at a makeshift shop. They planned to open up Tom’s compost toilets in his garden and set up a small bar so visitors could share drinks and explore the brewery and farm. It was a moment for them to share their passion and hear what others thought of their beers.

The Jacobs brothers thought 100 people might show up, maybe 200 if they were lucky. They were a tiny brewery producing esoteric beers. But word had travelled fast about Antidoot, from the Milk the Funk group and other Belgian beer circles into international online beer forums. New producers of wild beer often generate hype. But based on their homebrew experiments, expectations of Antidoot’s beer were high, and the rare nature of its limited production had only exacerbated the hype. That hype crashed down upon the Jacobs brothers at their Spring Release, and it crashed down hard.

From early in the morning, people started queuing outside Tom Jacobs’ home to get to the brewery. Tom could see that some people waiting in the line to buy beers were already trading bottles of Antidoot beer in private groups online, selling them for extortionate prices on the black market. When Tom confronted them, they shouted abuse at him about having to queue. After only an hour, all of Antidoot’s beer had been sold.

But the people kept coming. Cars, many with registration plates from outside Belgium, were parked in every bit of space on every street around Tom’s house, blocking neighbours from getting in or out of their homes. After receiving complaints, the police showed up to help deal with traffic. The queues grew, stretching back out onto the road. Some grew hostile because of the lack of beer, many having travelled long distances. The compost toilet was disrespected. People started to shout angrily at Tom’s wife Kristien, upset that everything had been sold out and demanding that she bring them bottles. “That’s not a fun atmosphere,” says Tom.

On the evening of the Spring Release, Tom was concerned that his family might be subjected to continued abuse because of his project. He was worried that the beers he had worked so hard to make would never get to those who might enjoy them the most. He feared that he was contributing to the sickness of a modern capitalist society, where the virtual—speculation and hype—often destroyed real experiences. And despite spending his every waking minute trying to contribute to the integrity of the food and drink culture of the Hageland, Tom feared that the Belgian beer world might look negatively on the storm of attention, potentially perceived by others in the industry as manufactured, or even arrogant.

A few months after the unpleasant Spring Release, Tom Jacobs read an article in Belgian newspaper De Standaard about a French winery in Bordeaux called Château Pétrus. Pétrus wines were highly coveted, partly for their quality (they are produced on an exceptional slope with blue clay soil) and partly for their scarcity (the vineyard covers only 11 hectares). A limited amount of Pétrus wine is released each year (the whole of Australia, for example, receives only 36 bottles). As a result, bottles of Pétrus were being purchased by speculators who resold them on the black market at huge markups, used as investments which would grow in value with each passing year the wines aged.

It was a practice which sickened the family owners of Pétrus as much as it sickened Tom Jacobs. In his view, these drinks were produced by passionate creators who had worked hard so that people could enjoy them, not to speculate and turn a buck. Pétrus was dealing with the same tensions as Antidoot. To combat the issue, Pétrus had introduced a customer questionnaire at the point of sale. Those found reselling the wine would be added to a black list.

Tom reached out to those online he found selling Antidoot beers on the black market and told them he would blacklist them. But those people moved the sales conversations from private facebook groups into private whatsapp groups and then deeper into the dark web. Tom began receiving emails from random people threatening to sue him. They argued that blacklists were illegal, that data protection laws prohibited it, and that when somebody buys something, it becomes property they own that they are legally entitled to sell. “I think they were especially afraid that I would share a list with others like Cantillon or Bokke, because some people make a living out of that,” says Tom.

Tom wanted to establish a more intimate relationship with the people buying his beers so that he could prevent Antidoot bottles being sold as investments for ten times their price. He had never wanted his beers to be exclusive. But he now believed a membership system might be the fairest way to ensure people could enjoy Antidoot bottles. “We had to do something,” he says.

On Tuesday 12 November 2019 at 13:23, Antidoot opened up registrations on their new membership scheme. Tom was hoping to fill 50 lifetime memberships at €200 each, and 250 one year subscriptions at €120 each. Each member would receive a welcome pack of 6 different bottles, as well as first priority on buying 6 large bottles for each of Antidoot’s planned seasonal releases in the following year. Half of Antidoot’s annual production would go to members. The other half would be reserved for bars and restaurants all over Europe to ensure non-members also had reasonable access to their beers.

Within 5 minutes of the link going live on Antidoot’s Facebook and Instagram pages, they received 800 registrations. A few minutes later, when the registrations were at more than 2,000, Tom Jacobs removed the registration links. Members were selected from the registrations at random, and each of the 300 successful applicants was asked to sign a contract, confirming the purchases were for personal consumption and agreeing never to sell the bottles they received. Any breach of contract would be enforceable in court. It wasn’t a watertight solution, but it would minimise black market activity and it sent a message from Antidoot to those in the beer world about its values as a brewery: their beers were not a commodity to be traded, but rather a creation which embraced local traditions and expressed the flavours of their terroir.

The following month, in December 2019, Antidoot hosted its first release day since the unpleasantness of their 2019 Spring Release. Only members were permitted to attend to collect their bottles and drink from the small bar. “It was really relaxed,” says Tom. “You could talk to everybody and it was kind of a community feeling with people sharing stuff.”

During the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Belgium beginning in March 2020, Wim Jacobs was moved to the COVID department of the hospital in which he worked. As a result, he wasn’t able to brew or bottle any more with Tom, who recruited the help of his wife Kristien for brewery work. While Tom wasn’t able to welcome people to the brewery, Antidoot members could pick up bottles at his house and the beer that had been reserved for hospitality in Belgium was welcomed as extra stock by importers. They’ve since opened up new membership spots. Antidoot now have around 400 members.

Tom Jacobs gave up his job as a philosophy teacher because he was growing uneasy with what he describes as the modern ethos of “working more and more for obscure ends”. But by his own admission, Tom Jacobs has never worked so hard as in the last three years of the Antidoot project. “But it feels different,” he wrote in a recent Instagram post. “It feels like the work is real, and the ends self-chosen.”

Like the increased workload of his new life, other elements of Tom’s transformation have been equally unexpected, whether that’s the uneasy acceptance of a farm life which includes the Spotted Wing Drosophila and severe climate change, or his pivot to what some may argue is an exclusive beer club that belies his democratic values. But Tom Jacobs was seeking embodiment, a tangible way to find balance between control and nature, and between mankind and the life around us. That struggle for balance is embodied in every bottle of Antidoot beer, each a symbol of Tom’s own personal journey and transformation.

Throughout the second Lockdown that began in October 2020, whilst restaurants and bars have been closed, Tom Jacobs has been brewing and farming in Kortenaken. He collects vegetable waste in a compost heap at the bottom of his fruit field, dead organic material, nutrient rich, decomposing over time. “In a way, compost is the perfect example of Alchemy,” he says. When the pile of rotted compost is large enough, he uses it to fertilise his other plants—the herbs in the garden and the fruit on his trees.

The compost is alive with organic material, coloured by the greens of leaves and grass and the browns of food scraps and wood chips. Fungi and earthworms move freely through it, the smell of earth another aromatic note in the fragrance of the Hageland countryside. Nothing is sterile here. There is no control. Every organism is working towards a decomposition on its own time and in its own way.

The resulting dead matter ends up feeding the organisms Tom Jacobs needs for fermentation—the wild yeast and bacteria on the farm—giving life to these indigenous cultures. “Death and life provide each other with balance,” he says.

Tom Jacobs is a philosopher as well as a brewer, and the life and livelihood he has built has its roots in a pile of compost at the back of his house, near to the grave of a dead lamb whose skull looks over the wild fermentation of every batch of Antidoot beer.

*