In one of the most complex border areas in the world—a village divided into a patchwork of enclaves where the borderline between Belgium and the Netherlands straddles farmland, roads, and houses—brewer Ronald Mengerink of Brouwerij De Dochter van de Korenaar strives to overcome imposed boundaries to create something unique.

Words by Oisín Kearney

Photography by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Breandán Kearney and Ciara Elizabeth-Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

I.

Wire of Death

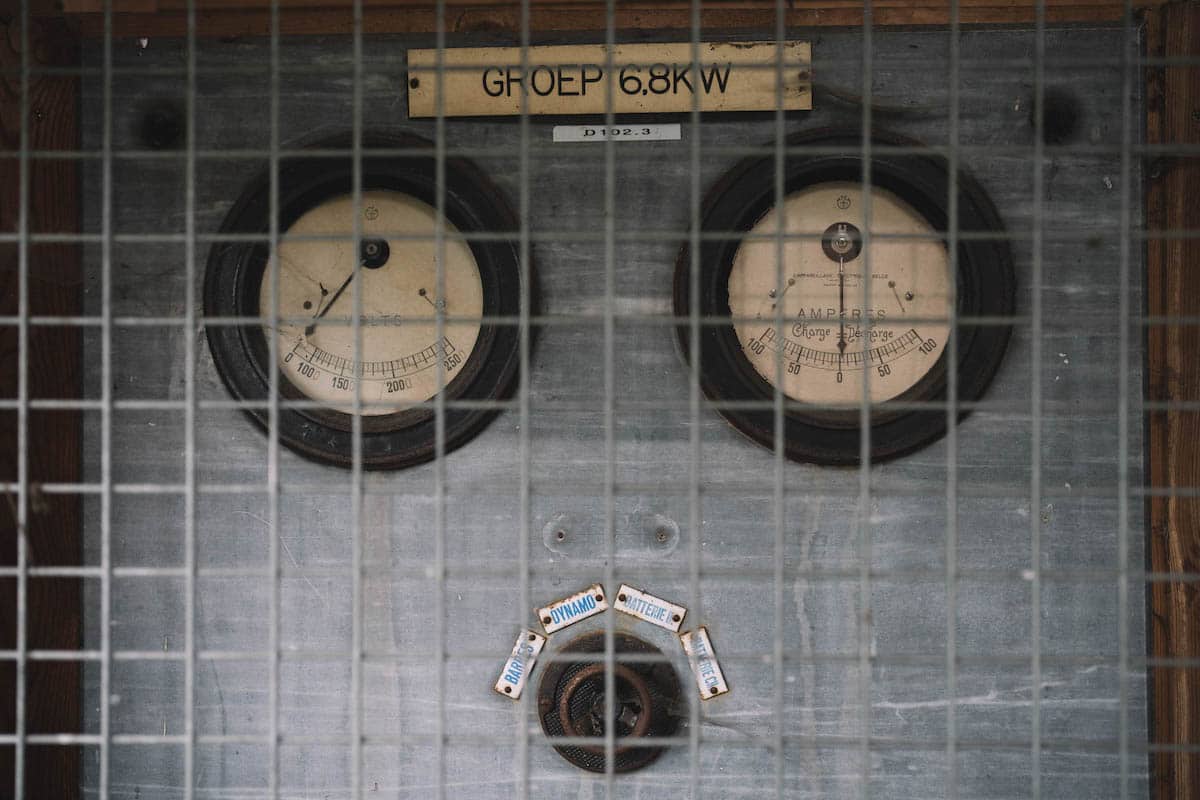

During World War One, the German Army erected an electric fence to control the Belgian-Dutch border, separating families, friends, and workers living in frontier towns. The 2000-volt Wire of Death (Dodendraad) was over 200 km long and in some places reached 5 metres tall. If they didn’t die from the shock, German guards shot anyone that came close to it. The total number of victims of the Wire of Death is estimated at 3,000 people.

One of the places most affected by the Wire of Death was Baarle, a village divided into a patchwork of Belgian and Dutch territories. The people of Baarle—whose lives were already made difficult by a chicken-wire fence erected around the village by the Dutch government as well as by the bizarre mapping of their home—were keen to subvert this new border by digging tunnels under it or pole-vaulting over it. Sometimes, they would squeeze an open beer barrel under the fence and crawl through without touching the wires. When the war ended in 1918, the locals on both sides of the border destroyed the much-hated fence.

There’s one brewery located in the village of Baarle today, an independent producer called De Dochter van de Korenaar, owned and operated by Ronald Mengerink and his family. Much like Baarle, Mengerink defies categorisation. He is a Dutchman. Who makes Belgian beers. With French names. And American yeast. He is a maverick who does not fit any mould, making both hoppy session beers and high ABV barrel-aged experiments in a village that defies cartographic sense. He’s been a chef, a seller of olives, a seller of sausages, a seller of cheese, and a builder of swimming pools. Today, he’s a brewer who merges disparate influences into something distinctly his own.

In 1982, when a 20-year-old Ronald Mengerink learned that he had failed a university Geography exam by one tenth of a point, he confronted his professor. Mengerink claimed he had answered the question correctly, but in his own way. His professor argued he should have used the exact wording he was given. Mengerink was furious. As he saw it, he had two options: accept the professor’s decision and repeat the year or drop out and forge a new future with different parameters. Preferring to make his own way rather than live by rules with which he profoundly disagreed, he chose the latter.

Ronald Mengerink and his brewery De Dochter van de Korenaar are living proof that in this life you don’t need to accept borders and boundaries and limitations imposed by others. You don’t need to stop at the fence. You can go under it, around it, through it. You can hop over it. You don’t need to make things in the traditional way. You can try things. You can fail. You can fail better. And in the process, you might create something beautiful.

II.

Sunrise and Sunset

In 2004, Ronald Mengerink made a short drive that would change his life. He helped his pregnant wife Monique de Baat and their two young children into the car and set off to their new home less than ten minutes away. Mengerink met de Baat years previously at a local market in Oosterhout, north of Breda, in the Netherlands. He was selling olives; she was selling fruit. She asked to buy some of his olives, and he asked her out on a date. It was his birthday, and although she initially said she wasn’t free, Mengerink won her over. They fell in love, got married, and would have three children together, setting up shop in the Belgian village of Weelde, in the municipality of Ravels.

They were uprooting the family now because Mengerink’s first brewery enterprise had failed miserably and they believed that a second brewery project—their final attempt and last hope—required a new start before their third child was born.

As a student during the 1980s in Groningen, a city in the north of the Netherlands, Mengerink had noticed an influx of specialty beers from Belgium and, confident that beer was a burgeoning industry, he had secured a loan from a bank to open a brewery. In 1984, with a loan of 50,000 Guilders—about €16,000 in today’s money—he opened Brouwerij De Noorderzon: The Northern Sun Brewery.

Mengerink always had a taste for beer. He was born in Eindhoven and grew up moving around the Netherlands. His parents worked as wedding planners and would host large wedding parties. As a three-year-old toddler, he would stumble around emptying all of the half glasses of beer whilst the wedding guests were dancing. “I remember that I liked beer just instantly,” reminisces Mengerink.

When he was nine, his family moved to Den Helder in the north, and then to Alkmaar. Mengerink began homebrewing at the age of 15, experimenting with oatmeal, baker’s yeast, and wild hops to make his beer. Despite the fact that his parents didn’t initially approve—“They declared me completely out of my mind when I told them the first time I quit my studies,” says Mengerink—he persisted, and even managed to persuade his parents to help him buy some oak barrels from a Geuze brewer.

Mengerink was only 22 years old when he opened De Noorderzon with the help of that loan from the bank. He was young and inexperienced in business. Interest rates were at 13%. He found it difficult to accumulate knowledge and build a network. “[The] Internet didn’t exist,” he says. “So you had to find everything for yourself.” He soon ran into financial troubles and started building swimming pools on the side to fund the brewery. But, after one and half years, he ran out of money. Mengerink returned to the bank to explain his predicament.

But Mengerink had not fully repaid his previous loan. The bank no longer agreed that “special beer” was a solid investment. They declined his request. De Noorderzon closed down and Mengerink spent the next three years trying to restart it. But without support from the bank, it was impossible to get the capital together. “I was quite poor and didn’t have a dime” he remembers.

After the failure of De Noorderzon, he had continued brewing as a hobby, especially in the winter months when his swimming pool business was quieter. But when his first child was born in 1999, Mengerink found himself at a crossroads: He could give up on his dream of a brewery and take on a different job which would ensure he could meet the financial responsibilities of being a new father; or he could show his son, through his actions, that you should follow your passion, even if it means butting up against limitations others try to put on you.

Mengerink started brewing semi-professionally, taking batches of 500 litres from Weelde to sell in France every summer. The idea worked, and from the profit, Mengerink was able to renovate a ruin in a small French township of only six houses on a forested hillside in Brittany. Mengerink planned to use the money from selling this holiday house in France to fund the building of his second brewery.

Ronald had his eye on a possible location for this—an affordable storehouse property in a place not far from Weelde. Mengerink drove less than ten minutes and pulled his car into this strange village located 50km north east of Antwerp. It was not like any village he had lived in before. It had two town halls, two councils, two mayors, and at that time, two fire services. This village was in two countries. This village was called Baarle.

III.

Border Town

Like Ronald Mengerink, Baarle is an outlier. It is one of the most complex border areas in the world. It is divided into a patchwork of enclaves, with the borderline straddling farmland, roads, and even houses. Of the roughly 10,000 inhabitants of Baarle, 3,000 live in the Belgian territory, Baarle Hertog, and identify as Belgian, whereas 7,000 live in the Dutch territory, Baarle Nassau, and identify as Dutch.

“An enclave is a piece of independent country in another independent country, completely surrounded by that country,” explains Willem Van Gool, chairman of the local tourism office. There are only 64 enclaves in the world, and 30 of them are in the Baarle area—22 Belgian enclaves inside the Netherlands and 8 Dutch meta-enclaves inside those. Van Gool, himself a Dutch passport holder, even though his mother is Belgian, speaks of Baarle with pride: “Let’s name this world capital of enclaves”.

The reason for this unconventional arrangement dates back to the feudal land agreements of the Middle Ages, when there were no countries. The area became known as “Baarle”, denoting the topography: baar, a bare, flat, or uncultivated land; and -loo, meaning forest on sandy ground next to a settlement. The suffixes “Hertog” and “Nassau” were added to refer respectively to the Hertog (or “Duke”) of Brabant, and the House of Nassau which held the Lordship of Breda.

The borders have been softened and hardened many times, including being unified under Napoleon Bonaparte’s First French Empire, only for the enclaves to stubbornly appear again in 1830 with Belgium’s independence. During World War I, Baarle Hertog became one of the few parts of Belgium not invaded by Germany, as it was surrounded entirely by the neutral Netherlands. It became a place of refuge for Belgians fleeing occupation and a hotbed of resistance and British espionage missions. There have been 15 attempts to change the situation, but like Baarle’s brewer Ronald Mengerink, the enclaves are persistent and have resulted in a unique way of life in this border town: a culture of bending the rules.

Baarle has in the past attracted those who wish to evade the authorities, such as a border-hopping pirate radio station, a money-laundering bank, and even a murder case where a body was found strewn across the border. Its main criminal enterprise, however, has always been smuggling. Over the years, the town became known for the smuggling of butter, sugar, gin, beer, and cattle as goods were moved across the border to make a profit from the difference in prices and tariffs.

This smuggling spirit is still seen today on the Hertog Hendrik I Plein in Baarle-Hertog, where a stone statue depicts a man with a bag of smuggled goods on his back. He is a pauper, an ordinary man just trying to get by, to make some extra money on the side, being creative in how he does it, but sometimes bending and breaking rules.

Another instance is beer shop and distributor De Biergrens (The Beer Border) who contract a beer called Smokkelaar (The Smuggler). It’s a Belgian Triple of 8% ABV, the label of which displays both Belgian and Dutch flags. The shop has the border running through the loading dock and right through the middle of the store, marked by a stripe where the Belgian and Dutch flags cross. The building was constructed here deliberately in the late 1990s to avail of the benefits of selling beer on the border. Today, Belgian beer is almost one third cheaper than in the Netherlands, so hordes of Dutch customers come here to purchase their alcohol and “smuggle” it back across the border.

Elsewhere in Baarle, Belgian restaurants have been known to move tables across the border to take advantage of the more lax closing times in the Netherlands. Dutch teenagers can be refused service in a Dutch bar, where the legal drinking age is 18, and simply walk across the road and drink in Belgium, where the legal drinking age is 16. They can also pop into a shop to buy fireworks, where it is much more lenient than in the Netherlands.

The two villages have to talk a lot to get things done together. The two councils cooperate on roads, waste disposal, and utilities. The two police forces come together to collaborate in one room. The two fire brigades amalgamated into one station. More recently, they are working together to plan the construction of a new centralised cultural centre straddling the borderline itself, to include a music academy, the library, and several social, cultural, and youth organisations. Frans du Bont, the Belgian Mayor of Baarle Hertog, compares it to a marriage, but one in which there’s no possibility of divorce. “We are condemned to each other,” says du Bont. “We want to be condemned.”

Decision-making may be unconventional and long-winded, but the results serve the local people well. Du Bont argues the overarching spirit of Baarle is not in evasion, but in being flexible. His wife is Dutch. Two of their four children are Belgian and two are Dutch. In Baarle, you choose the national identity you want. You choose who you want to be.

When Ronald Mengerink pulled into Baarle with his family, the village didn’t have a physical brewery. This bizarre place was perfect for a new start. He was attracted by its fluidity of identity and its mould-breaking spirit. And so he set up in the border town. He just had to make sure that it didn’t fail as De Noorderzon had. It was time to get to work.

IV.

The Front Door Rule

Ronald Mengerink found a place on Pastoor de Katerstraat—a street of about 500 metres in length where the international border cuts through on three separate occasions. The small house number plaque showed a Belgian flag, indicating that his address was in Belgium, not the Netherlands. In Baarle, a “front door rule” (voordeurregel) determines in which country a house is located by where its front door lies. Several buildings are split in two by the border. One particular Dutch house has only its toilet in Belgium.

The national boundaries were only finalised on maps in 1995, being named H1, H2, H3 etc for Belgian enclaves and N1, N2, N3 etc for those in the Netherlands. Famously, an 84-year-old Belgian woman woke up and discovered that the border had moved a few feet to the south, and that her front door was now in the Netherlands. A proud Belgian, her solution was to swap the door with the window on its left, effectively moving the house back into Belgium.

Mengerink’s new abode had a little storehouse of about 120 square metres and he began brewing 10 hectolitre batches of beer in his second brewery—De Dochter van de Korenaar.

“It means beer,” Mengerink says of the name. He came across a story about Emperor Charles V preferring the juice of “the daughter of the ear of barleycorn” more than the blood of the grapes.

Mengerink agonises over the names of his beers, the process involving what he says are “sleepless nights”. He planned to name his first beer, a Belgian Blonde of 5.5% ABV, “Goesting” (meaning “desire” or ”appetite” in Flemish), but he thought international markets in the UK and France wouldn’t understand it, never mind be able to pronounce it. So he changed it to “Noblesse”. The next beer was “Braveur”. The French names honoured how the finance for De Dochter van de Korenaar came from selling the family’s French house. Just as his brewery sits on the international boundary, De Dochter Van de Korenaar defies national borders: “So now we have a Belgian brewery, but a Dutch brewer,” says Mengerink. “And French names.”

In 2014, Mengerink moved the brewery to Baarle’s Gierlestraat, doubling its capacity. Then, in 2017, he bought a farmhouse in Oordeeldedstraat, enabling him to brew up to 50 hectolitres at a time. The new property has a large brewing space, a bottling plant, a conditioning room, a warehouse, and even a cellar for the maturation of the special “wood finishes”. It sits just inside H8, the second largest Belgian exclave in Baarle. It’s the only building on his road that is on a Belgian plot. All the neighbouring properties are on Dutch territory.

Even within the small confines of its own street, De Dochter van de Korenaar stands out as different.

V.

“The Treasure Room”

Ronald Mengerink’s cellar—what he calls “the treasure room”—can store up to 700 barrels. The air is a cool 13 degrees Celsius all-year round, with jenever barrels, whisky barrels, and Brunello di Montalcino barrels.

“Many other brewers that do barrel ageing, they keep it at room temperature or even increasing temperature,” says Mengerink. “So the beer is forced into the wood in summertime and squeezed out in wintertime”. The lower cellar temperatures ensure Mengerink can age beer for long periods without risk of acetobacter infection or rapid oxidation.

He claims to be the first Belgian brewery to start barrel-ageing beers to attain the flavours of what was previously in the wood, and one of the few brewers that uses new oak barrels to experiment with varieties of oak, duration of ageing, and toasting levels. Each barrel has a different toasting that is ascribed to ageing different types of beer. The lighter the toast, the lighter the beer. The heavier the toast, the darker the beer.

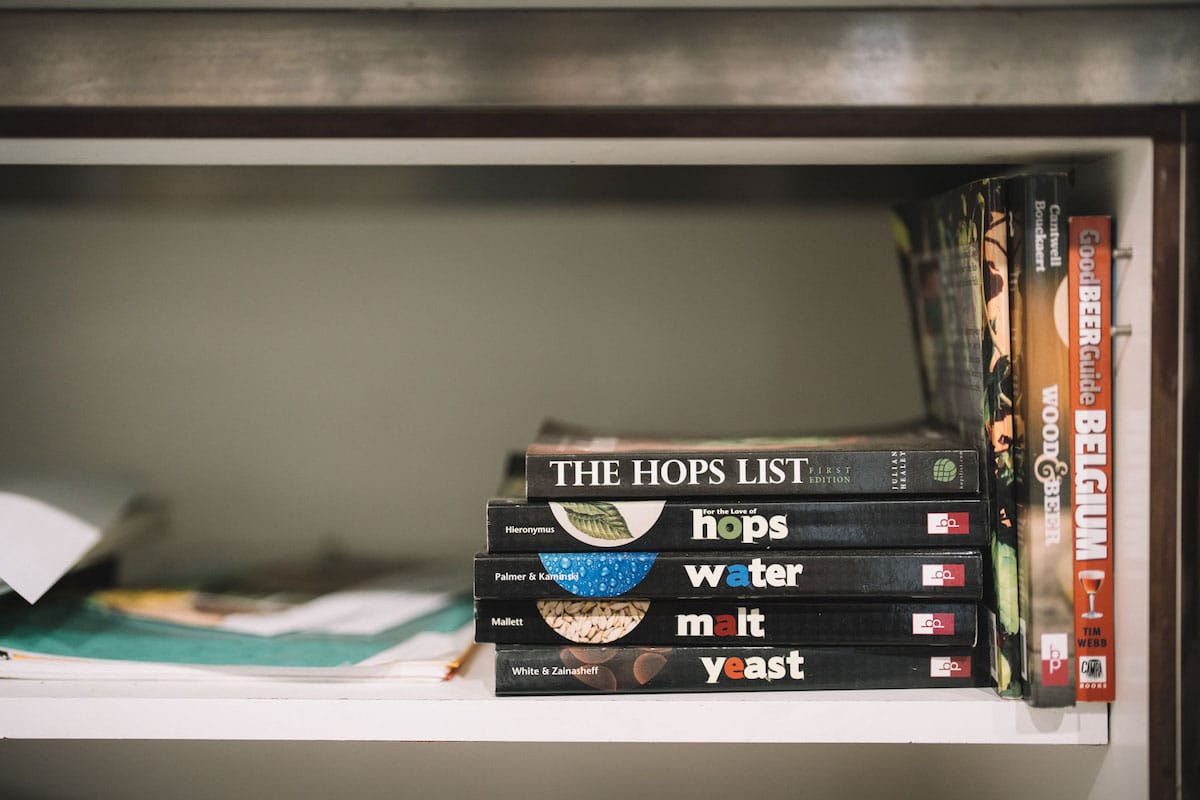

Mengerink sees his beers not as exclusively “Belgian” but as “international”. In 2008, he visited the United States and drank a Bell’s Two Hearted IPA. He was stopped in his tracks by the Centennial hops that give it a piney, bitter flavour, and as he continued his journey into American IPAs he was continually surprised by the bold fruity flavours they offered.

Back home, he started experimenting, using European hops as a base and adding a variety of American hops as “the cream on the pudding”. Eventually, he created the Belle-fleur—a thirst-quenching IPA of 6% ABV with bright citrus flavours.

Mengerink’s experimentation continued. After a visit to Porto, Mengerink had the idea to use the same method to produce a sweet Port from beer. He began brewing an American barleywine, and after a few days, he stopped fermentation by adding grain alcohol. He then aged it in Port barrels, sometimes for as long as 6 years. The result was a 19% ABV beer called Rien Ne Va Plus (Nothing Goes Anymore), perhaps inferring that as far as brewing was concerned, the rulebook was out the window. “It’s something really new,” he says. “I believe I’m the only brewery in the world making something like that.”

La Renaissance Grand Cru is the product of another experiment. It’s a 7% ABV classic English IPA with a dry, fruity, and bitter flavour profile and notes of wood, spice, and vanilla. It’s brewed using Maris Otter malt and East Kent Goldings hops, then matured for 2.5 years in Puligny-Montrachet white Burgundy barrels. Just before bottling, the beer is dry hopped with Nelson Sauvin. “You can really taste it,” says Mengerink of the white wine notes of both the barrels and the Sauvin hops. “And then the smooth bitterness of the beer.”

Once a year, Mengerink brews L’Ensemble, a full malt barleywine of 13% ABV which also plays on the boundaries of wine and beer. L’Ensemble is fermented with both beer and wine yeast.

There’s a picture hanging in Mengerink’s brewery; a staged photograph of the Last Supper. Instead of Jesus and the apostles, it depicts Ronald Mengerink and his friends, son, and brother-in-law enjoying their L’Ensemble di Montalcino, a concoction he’s matured in Brunello di Montalcino barrels sourced in Castello Banfi in Italy, when he visited the cantina of the owner of chocolate and confectionary companies Nutella and Ferrero Rocher. It’s a full malt barrel-aged barleywine of 13% ABV, which he and his apostles often enjoy with grilled red meat, old cheese, and dark, dark chocolate.

VI.

“Coming To Beer”

Willem Van Gool is an old friend of Mengerink’s as well as a tourist office official, and Van Gool’s son has even worked at the brewery. “He was always sure about his ideas” says Willem Van Gool of Mengerink’s brewing. “What is in his head, he makes.”

Van Gool testifies to the difficulties Mengerink faced when creating such experimental beers. It was tough for Mengerink to break into the Baarle community because his beers were often complex in character and sold at a higher price point. “Not everyone was loving this taste,” Van Gool admits. Furthermore, it was difficult for Mengerink to win over the Belgian beer community. “All the Belgians thought ‘that’s that Dutchman’,” says Van Gool. “‘Dutchmen can’t come to beer’.”

Mengerink admits that his beer is more bitter and less sweet than the majority of commercial Belgian beer. But for him, most commercial Belgian beers are too sweet and not bitter enough. He didn’t feel the need to seek approval. “I don’t want to push people to drink my beer,” says Mengerink. “You don’t have to drink it. If you don’t fancy it, then go on drinking Duvel.”

Since De Dochter van de Korenaar was conceived 15 years ago, the beer market has exploded. When Mengerink began, there were about 130 breweries operating in Belgium. Now, there are over 400. There’s also been a rise in the number of what Mengerink calls “beer firms”—businesses who contract breweries to make their beer—from around 40 when Mengerink started in Belgium to over 300 today. “There’s too many sharks in one pond,” he says of the market.

In 2009, only two years after he set up De Dochter van de Korenaar, Mengerink snatched the Goudse bierprijs—the Gold beer prize from Belgian beer consumer group Zythos—for his first beer Noblesse. This was followed in 2011 by him picking up the European Beer Star award with L’Enfant Terrible, a 7% ABV Amber Sour. “After that, it started booming,” says Mengerink.

De Dochter van de Korenaar won several Zythos consumer trophies and Brussels Beer Challenge awards and in 2019, L’Ensemble was listed by Ratebeer as one of the Best Beers in the World. The Belgian brewing community took note of the international awards. Dutchmen could come to beer. The international attention also pricked the interest of locals in Baarle. “Everybody was thinking, dammit!,” says Willem van Gool. “That beer has to be good.”

VII.

Shutdown

The brewery was now growing at more than 100% a year. Monique de Baat quit her job as a teacher to help run the brewery, agreeing to manage the book-keeping. But recent years have seen the emergence of new limitations forced on De Dochter van de Korenaar by difficult external circumstances.

In 2020, restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic differed between Belgium and the Netherlands, as both countries took very different approaches to handling the coronavirus. Baarle now had two sets of restrictions to manoeuvre. Baarle-Hertog Mayor Frans du Bont explains how the Belgian side of the village closed the border with breeze-blocks and containers—a strict lockdown.

Whilst Dutch people could continue going about their business, Belgians were told to stay inside. Whilst Belgian bars were closed, Dutch bars remained open. Baarle’s Zeeman’s outlet, a chain known in both countries for cheap clothing, is physically cut in half by one of the enclaves’ borders. The side of the store in Belgium was blocked off with tape, meaning customers couldn’t cross the store to pick up underwear. As Belgium and the Netherlands altered their restrictions and COVID policies, the people of Baarle had to bend around them. “It was changing from week to week,” DuBont remembers.

De Dochter van de Korenaar was forced to shut down its operations. And then, in the summer of 2020, Ronald Mengerink lay seriously ill in a hospital bed with COVID-19, the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7) of the first wave. He suffered not only from COVID-19, but contracted pneumonia and a kidney infection.

After he was released from hospital, he felt very sick for four weeks. It took five months of being isolated in his bedroom, with his family shoving food under the door, before he was back on his feet. He suffered rapid weight loss from not eating. “In 15 years I gained 15 kilograms, every year 1 kilogram from the beer,” he says. “And then in three weeks I lost it.”

The business pivoted, selling beers online. But then the outbreak of the Ukraine War, and the resultant energy crisis.

Mengerink says malt prices have almost doubled and that the price of glass and carton have gone up substantially. He says the price of gas is now five times higher than it was before, rendering the whole brewing process much more expensive. Mengerink has tried to reflect this in the cost, but it is a constant challenge to increase prices of speciality beer product without it having an impact on the growth of the business. “We increased our prices by 4%, but it was based on the prices of January,” says Mengerink. “And now we have to do a second raise, maybe even close to 10%”.

VIII.

L’Ensemble

In the midst of all these challenges, the two villages of Baarle came together on a sunny day in September past to celebrate the “Hop over de Grens” (Hop over the Border) Beer festival, a local initiative that sees brewers from both sides of the border set up stalls on the borderline and sell their beer to raise money for charity. The beer of De Dochter van de Korenaar was sold out.

Belgian and Dutch people mixed together, enjoying each other’s company, sharing conversation and ideas. It was the fifth instalment of the festival, another example of how the people of Baarle continue to work together under difficult circumstances to ensure these boundaries don’t impact their lives and their friendships.

On the exact spot where the festival takes place along the international border, the two villages of Baarle-Nassau and Baarle-Hertog are working together to plan the construction of their new cultural centre. There will even be a swing, so children can swing across the border from Belgium to the Netherlands and back. Willem Van Gool muses that the idea is to celebrate their situation and create “a real border area, but not with trenches.”

When locals from Baarle tried to cross the Wire of Death during the First World War, they would use wooden beer barrels to hold up the electric fencing so they could climb underneath.

Today, through initiatives such as “Hop over de Grens”, the beer barrel is still being used to evade borders. At the centre of it all is a man who failed his university Geography exam, but still doesn’t accept that he got it wrong.

*