In the 1970s, the Belgian endive (also known as “Witloof’, “Chicory”, or “Chicon”) was the King of Belgian agriculture, accounting for a quarter of all vegetables grown in Belgium. Today, it has almost disappeared. Will those involved in its cultivation agree on how to preserve Belgian endive before it’s too late?

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Food Group” series. Read more.

On Thursday 11 January 2018, 25-year-old Yannah Cornelis, a recent graduate of bio-science engineering from Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, went for a job interview in the village of Herent at the Nationale Proeftuin Voor Witloof. Cornelis was originally from Herent but lived in the nearby University city of Leuven. She wanted to work in the village where her parents and her grandparents lived, and where she still organised weekly gymnastic training for local children between the ages of 3 and 18 years.

The Proeftuin—the National Testing Garden for Belgian Endive in Belgium—was the government funded research centre for Belgian endive. If the town of Herent was the vegetable’s blast zone of farms, then the Proeftuin—with its research projects and informational resources—was Belgian endive’s ground-zero.

Yannah Cornelis was interviewed by two people: the Director of the Proeftuin, Tim De Clercq; and Bram Van de Poel, a Professor at KU Leuven. She was interviewing for the position of research assistant on a joint project between the two institutions which sought to create a seedbank of special “heritage” Belgian endive seeds, those grown and selected over generations by traditional producers. The seedbank’s goal was to preserve the diversity of those heritage seeds at a time when Belgian endive farmers were disappearing at an alarming rate. Without the heritage seeds, Belgian endive would struggle to survive.

Belgian endive is also referred to in English as “Chicory” and translates into French as “Chicon”, but it’s best known in its native Flemish Brabant as “Witloof”: literally “White Leaf”. It’s a unique vegetable in its appearance, a torpedo head of tightly packed white leaves which have a slightly bitter taste and offer various culinary opportunities. Unlike most other vegetables, however, it has to be grown twice, once to extract the root from the seed, and the second time to “force” the root under cover of complete darkness to develop its distinctive pointed cigar shape.

Bram Van de Poel, a research Professor in the KU Leuven Biosystems department with expertise in plant physiology, had just inherited his lab from the retiring Professor Maurice De Proft, a well-known scientist who had been studying Belgian endive for years.

At the interview, Cornelis was nervous, but exuded a quiet confidence. Van de Poel asked her about her interests in agriculture and her experience with Belgian endive. Cornelis explained that her grandparents, Yvonne Heremans and Willy Perdius, had grown it there in Herent. She still has some old photographs of them planting roots in the garden and she remembered eating Belgian endive every time she visited. Van de Poel had picked up a passion for Belgian endive from his grandparents too. “My grandfather was into hobby gardening,” says Van de Poel. “He was the one that sparked my interest in nature and plants in general.” It turned out that both Cornelis and Van de Poel, as undergraduates, had been taught courses by Professor Maurice De Proft.

Top Right: a head of Belgian endive.

Bottom: A researcher at the Nationale Proeftuin voor Witloof in Herent carries out tests.

The day after her interview, on Friday 12 January 2018, Yannah Cornelis received a phone call from Tim De Clercq, the Director of the Proeftuin. De Clercq informed her that the job as researcher was hers if she wanted it. A few weeks later, in February 2018, Cornelis began to work on the Belgian endive seedbank which her team hoped would preserve what they called “growers’ selection lines”.

Cornelis would be working alongside Van de Poel, establishing storage options, and data archiving, and developing variety by securing ancient lines of seeds from other banks such as the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics in Germany. But crucially, she would be driving around the province of Flemish Brabant to speak with farmers to try to collect their seeds and establish as diverse a collection of witloof heritage seeds as possible.

Belgian endive farms were disappearing every year. The time and labour intensive nature of traditional ways of producing the vegetable and the plummeting prices in retail made it unattractive to younger farmers. Aging growers were retiring en masse. The capital costs associated with recent, more technologically advanced methods of growth were prohibitive.

It was a dream job for Cornelis who had grown up eating Belgian endive with her grandparents in Herent, where the Proeftuin was located. Perhaps in some small way, she could help to secure the future of the vegetable.

There are several stories about the “discovery” of Belgian endive. The most likely takes place in the winter of 1834 when Frans Brezier, the head gardener at the Brussels Botanique in Schaerbeek was said to have thrown unknown roots that the institution had received for scientific experiments on a pile of earth in the Botanique garden, covering it with a layer of loose soil so the garden looked tidy. It’s said that a few months later, he came across a small white point poking out from the ground and when he removed the soil, he saw that it had developed white leaves shaped into a point. Noticing that the special crop liked darkness, warmth, and humidity, Brezier took the other roots in the pile and put them in his cellar, covering them with a layer of soil so they wouldn’t dry out. After the winter, he dug up the roots again to discover that they all boasted a white foliage. He tasted them and the rest is history.

Top right: Bedding in of Belgian endive roots (dated 1935) / © Photo: Collectie Familie P. Cnops

Bottom: Cleaning and sorting of Belgian endive heads (dated between 1970 and 1980) / © Photo: Centrum Agrarische Geschiedenis (CAG)

Belgian endives are versatile in cuisine. When raw, they are crisp and bitter, making them a great addition to salads. Their long cupped leaves are often used as small serving platters for cheese and nuts, sprinkled with herbs and drizzled with vinaigrette. They provide the bitter backbone to sweeter salads containing plums, apple, and lemon-honey dressings. Very commonly, they are served with mayonnaise in accompaniment to steak. When cooked, the sharper flavours of Belgian endive soften into a mellow, nutty sweetness, most often seen in dishes such as braised Belgian endive, or rolled in ham and covered in a creamy sauce with gratin dauphinois. It’s also incredibly nutritious. Belgian endive is low in calories and sodium, and rich in vitamins, minerals, and fibre.

Belgians are proud of their witloof, perhaps because it mirrors the qualities embedded in their national character: from the soil, as the Belgians keep their feet on the ground; difficult to grow, as the Belgians are stubborn; and unlike any other vegetable, as the Belgians are unique.

The vegetable appears in dishes, not just in fancy restaurants, but in village corner brasseries and family homes. Belgian chefs such as Jeroen Meus and Peter Goossens wax lyrical about witloof in their books and TV shows. Its roots have traditionally been used to produce a chicory coffee in Belgium. There’s a witloof festival in the Belgian town of Haren, with exhibits on farms, the serving of dishes, and a “Chicon Run”. Between 1954 and 1977, there was an annual Miss Witloof competition in Belgium. There’s a beer company located in Brussels called Brasserie Witloof. Brouwerij Hof ten Dormaal use the root of the vegetable to enhance bitterness in one of their beers, a Belgian ale of 8% ABV called Witgoud, or “White Gold”. There’s even a Witloof museum in Kampenhout.

Top right: Miss Witloof 1970 (dated 1970) / © Photo: Collectie Witloofmuseum Kampenhout

Bottom: The exterior of the Witloof Museum in Kampenhout

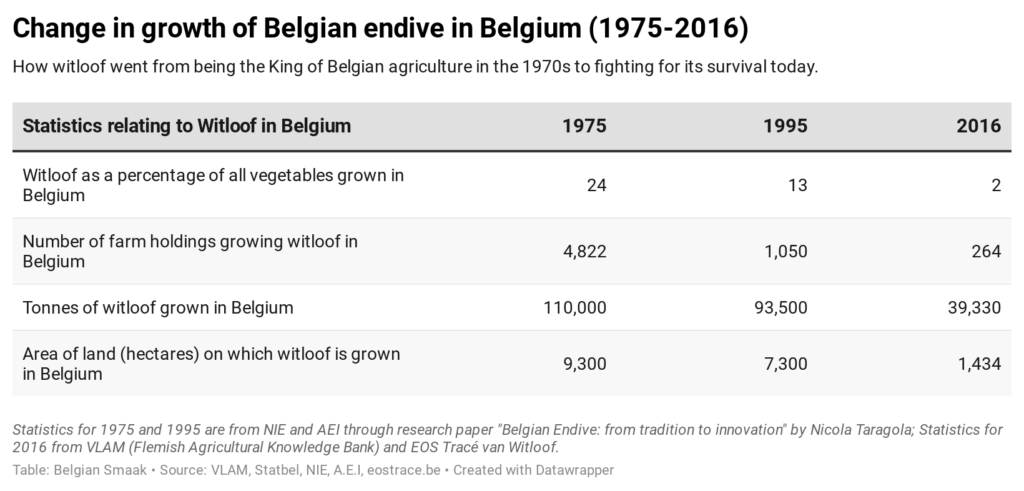

But the very existence of witloof is under serious threat. In 1975, it was the most grown vegetable in Belgium, making up 24.4% of all vegetables grown in the country. In that year, there were 4,822 farm holdings in Belgium producing a total of 110,000 tonnes of witloof across an area of 9,300 hectares. Fast forward to 2016, and there were estimated to be just 264 witloof farm holdings, producing only 39,330 tonnes of witloof across 1,434 hectares.

Last year Belgian endive made up less than 2% of the country’s total vegetable production. Growth of tomatoes, leek, mushrooms, and lettuce have all surpassed it.

Earlier this year, the Witloof Museum, operating since 2004 from its location on the Leuvensesteenweg in Kampenhout, closed its doors. Like the dark spaces Belgian endive needs to thrive, the lights were turned off indefinitely. It was once a bustling tourist destination where locals and international tourists came to learn how Belgian endive was grown and used in local cuisine, but now the outside of the building is dishevelled, its painted colours fading and in places peeling off, the inside an abandoned office with carpet edging up at the floor corners and walls bare of pictures.

Many farmers, scientists, and traders believe that in as little as 20 years, witloof will not exist at all. Jan Pasteels, a traditional grower of Belgian endive, makes his opinion perfectly clear: “There’s a better chance of it dying than surviving.”

Before Yannah Cornelis and Bram Van de Poel could start collecting the seeds, they would need a way to store them for as long as possible, so Cornelis split her time between the Proeftuin and KU Leuven, working with Bram Van de Poel to carry out testing on the best storage methods. They eventually decided that they would store whatever seeds they were able to collect in liquid nitrogen, at -196°C, in collaboration with a partner located on the KU Leuven campus, Bioversity International. “In that temperature, we can store them for eternity,” says Cornelis. She developed a system for data input and labelling which involved carrying out detailed questionnaires with farmer donors. But one of Cornelis’ main tasks would be to raise awareness of the collection among as many seed-selecting Belgian endive farmers as possible. To have a collection, you need seeds to collect.

Cornelis and Van de Poel, now forming a strong working relationship based on mutual respect and a shared passion, produced a short press release which they hoped would grab the attention of the growers and prompt them to get in touch. They targeted their agricultural connections, farmers newsletters, and scientific communities, but they also targeted mainstream media in a hopeful attempt to widen their pool.

They thought it was unlikely that the bigger networks would be interested in running stories of a niche scientific project about a Belgian vegetable nobody seemed to care about any more, one which was being grown less and less every year. But they hoped that the newsletter of a farmers union might pick it up, or maybe even a local newspaper. Anything to generate a few extra seed donations that might improve their collection. Cornelis was shy, but, for the good of the project, Van de Poel encouraged her to speak with any media that might get in touch.

Almost immediately after Cornelis sent out the press release, she began getting calls and emails from national newspapers, TV and radio stations, and news websites. The project was covered in national broadsheets and in publications in Dutch, French, and English: De Standaard, Het Nieuwsblad, Gazet van Antwerpen, Leuven Actueel, Flanders Today, Het Journaal, and Bruzz. For perhaps the first time, mainstream Belgian journalists wanted to talk about witloof seeds.

On 6 August 2018, a crew from national television broadcaster VRT came to interview Cornelis for the evening news. As part of the segment, during which she explained the purposes of the project in a short interview, she took them to the farm of Belgian endive growers Danny & Bieke Schoevaerts, and showed them the witloof roots growing in the fields of the Proeftuin. “I didn’t tell it to many people because I was a bit embarrassed to see myself on TV, but my family and friends were proud, and also really interested in the project,” says Cornelis. “People know witloof. But they don’t know how it’s produced. It’s really odd to see yourself on TV. And to hear yourself talk. but I’m glad we did it, because we got a lot of attention that way.”

The Belgian public were fascinated. Belgian endive was a part of their national heritage, but many Belgians had no idea that the vegetable was in danger of disappearing. Cornelis and Van de Poel’s project had tapped into a nerve in Belgian culture, and now they hoped that growers all over the vegetable’s home in the province of Flemish Brabant would get in touch. Perhaps their collection would be valuable. Maybe Belgian endive could be saved after all.

On Friday 29 June 2018, the Nationale Proeftuin voor Witloof in Herent hosted an “Open Field Day” at which Yannah Cornelis presented her project to farmers of Belgian endive in attendance. Cornelis was excited to talk to the farmers about how important the seedbank was and hoped that the farmers would agree to contribute their heritage seeds to the Proeftuin and KU Leuven.

Two of the farmers in attendance that day were Jan Pasteels and his wife, Ingrid Dockx of the Hof De Soete farm in Herent, located closeby to the Proeftuin. Cornelis had never met them before, but when she did, she learned that they were sceptical about handing over their seeds. Some of the other farmers seemed reluctant to contribute their heritage seeds too. Cornelis wanted to find out why.

Pasteels parents had been witloof growers in Boortmeerbeek, a village 8kms to the north where he had grown up. Dockx grew up in Sint-Katelijne-Waver, to the north east of Mechelen where her family traded vegetables.The couple started growing Belgian endive themselves in 1985.

Top middle: Belgian endive roots are collected from the field (© Photo by Jan Pasteels)

Top right: Ingrid Dockx beds in the Belgian endive roots for “forcing” (© Photo by Jan Pasteels)

Bottom: Jan Pasteels pictured in front of his Hof de Soete farm

Like many of the farmers in attendance at the Open Field Day at the Proeftuin, Pasteels and Dockx grew Belgian endive in the traditional way, using the best witloof roots they selected from the previous year’s crop to generate seeds for roots in the future. When these new “heritage” seeds gave them roots, they would harvest those new roots, and then replant them in a different section beneath the soil, essentially “forcing” the white leafed rocket heads to grow under cover of darkness. They avoided light not only by covering the witloof with soil but by placing large metal semi-circular plates over the areas of growth. Any light that might penetrate would encourage photosynthesis and turn the beautiful white leaves of the Belgian endive an undesired green, spoiling their crisp bitter taste and making them unsuitable for sale with supermarkets.

It’s because of the hand labour and special care at every stage of this process that traditional witloof producers in soil develop a high quality of witloof, and the natural selection year on year, stretching over generations, make these seeds genetically diverse and complex. It’s these heritage seeds—vanishing year on year as the farms which select them cease to grow witloof—that Cornelis and Van de Poel were hoping to preserve. This traditional method of production produces “soil Belgian endive” or as it’s known in its heartland, “grondwitloof”.

At her Open Field Day in June 2018, Cornelis showed growers around the Proeftuin, including the darkened rooms where they did tests using the less traditional method of production of witloof which had been developed by engineers in the 1970s. In this “other” method, the seeds still needed to be planted in the soil to develop the roots, but once you had the roots, you did not need the field anymore. The roots were planted in trays filled with water dosed with nutrient solution and stacked tray on tray on top of each other, often eight or nine high in large dark warehouses. In this way, you could produce a lot more witloof than in the traditional way and because of nutrient solutions, it could be forced much quicker, meaning more witloof more often. Because of the use of water, this method is described as hydroponic cultivation and the produce known as “hydrowitloof”.

The farmers in attendance looked into the rooms at the Proeftuin containing hundreds of trays of hydrowitloof. The quicker time in hydro production than in soil production affected how the witloof developed in size and shape, as opposed to the slower and cooler growth of grondwitloof. In addition, hydro growers used seeds from commercial seed companies which had been crossbred and genetically engineered to be homogenous, carrying certain positive characteristics in terms of yield. But because of their simpler genetic make-up than those selected year on year by the grondwitloof growers, the hybrid seeds became almost useless after a few generations. And if there was a problem with one crop from a hybrid seed, there was a problem with your whole crop. “Hydro is a factory,” says Pasteels.

Bottom: Yannah Cornelis in a “forcing” room at the Nationale Proeftuin voor Witloof carrying out tests on hydroponically produced Belgian endive.

Tension had started building between the grondwitloof farmers and the hydrowitloof farmers. The grondwitloof growers were working seasonally as they always had done, whereas the hydrowitloof growers could produce witloof all year round in their dark warehouses and hydroponic trays. Suddenly, retailers and supermarkets were buying only from hydro growers because of the stability of year round production. Consumers often preferred traditional grondwitloof to hydrowitloof for its quality and for its story, but they were often not made aware of what they were buying. In supermarkets, the prices of witloof fell dramatically as hydrowitloof could be offered at much lower prices given it’s larger scale production, quicker cultivation, and less demanding labour requirements.

After five years, the pressure on Jan Pasteels and Ingrid Dockx had became too much. “We stopped because we couldn’t make a living out of it,” says Pasteels. In 1990, they ended their grondwitloof business and tried to making a living in the business of transportation.

Such was the demise of grondwitloof at the hands of hydrowitloof that a group of 250 grondwitloof farmers got together to try to do something. They felt that if they could convey to the consumer how different production of grondwitloof was to hydro cultivated witloof, that they could ask for higher prices and thus save their livelihoods and the heritage of grondwitloof. They successfully created a brand—”Brussels Grondwitloof”—for which they secured a European Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), a label which is awarded by the European Union to protect the names of special agricultural products that are linked to a specific territory or authentic production method.

Another label, Belgian rather than European—”Brabants Grondwitloof”—was created for those growing in the soil but using hybrid seeds instead of their own heritage seeds, and whose farms did not meet the geographical requirements. The labels meant that grondwitloof growers could legally differentiate themselves from hydro. With consumers now able to see what they were buying, traders and retail were willing to offer growers of grondwitloof more money than hydrowitloof growers for their product. In 2010, Pasteels and Dockx became Brussels grondwitloof producers again.

The most important criteria to produce Brussels grondwitloof according to this label was that it should be grown in the soil, the witloof heads completely covered by earth. It also needed to be grown in its traditional heartland, a specified geographical region in the Brussels-Mechelen-Leuven triangle. Further, the seeds used to generate the roots for forcing needed to be selected and grown up from previous yields by the farmer, essentially creating a natural selection which promoted biodiversity, genetic strength, and heritage varieties of grondwitloof. It is these Brussels grondwitloof seeds that Van de Poel and Cornelis hoped to collect and protect.

The truth is that hydrowitloof is fighting for its survival today as much as grondwitloof. Because of aging equipment which needs replaced, equipment that is expensive and high maintenance, and because of the much smaller profit margins they are able to secure from supermarkets, the existence of hydroponically cultivated witloof is under threat too.

One major advantage of the heritage seeds and the traditional way of growing in the soil over hydro production relates to the “heart” of the witloof, a hard section through its centre. The smaller the heart, the softer the vegetable will be, and the more desirable it is for culinary purposes. Because of the heritage selection, slower growth, fewer available nutrients, cooler temperatures, and manual attention, Brussels grondwitloof is well known for having much smaller and softer hearts than witloof produced through hydro cultivation, more in demand from chefs. Sometimes the heart is so big in hydro, that it protrudes from the point, giving crossed leaves on the top. Such a witloof is considered poor quality. Much of the work of the Proeftuin, Cornelis soon learned, was in studying characteristics such as the size of the heart.

After her presentation to the grondwitloof growers, several growers told Cornelis that they would not be contributing their seeds. Confused, Cornelis enquired as to the reason. Jan Pasteels and Ingrid Dockx told Cornelis that forty years previously, a similar project organised by KU Leuven had attempted to create a seedbank of heritage seeds. The project had been led by Professor Maurice De Proft, the lecturer from whom Cornelis had received classes and the same Professor who had passed on his witloof lab to Bram Van de Poel. Pasteels and Dockx told Cornelis that those seeds had then been given to a large Dutch seed breeding company called Enza, and that Enza had used those seeds to produce hybrid seeds for commercial gain. It was the first time that Cornelis had heard of this.

“I don’t think she saw what was going on,” said Jan Pasteels of Yannah Cornelis. “But of course, we know about what happened 40 years ago. And it’s the same story all over again.”

It explained why Brussels grondwitloof growers had been reluctant to donate their seeds to the collection. They had trusted KU Leuven. And they felt betrayed.

In the mid-1980s, Maurice de Proft had undertaken a similar project based on very low level funding from KU Leuven to establish a seed bank of growers’ selection lines from Brussels grondwitloof farmers. De Proft was every bit the science professor: flowing silver locks and a white Santa Claus beard, balding head, and a curious disposition fitting of an ambitious academic. At the time of his project, the numbers of grondwitloof growers in Belgium were much greater than now and there was the possibility of collecting a larger genetic diversity of seeds. His goal was the same as Van de Poel and Cornelis: to safeguard heritage seeds before they became lost forever.

De Proft was not only a Professor at KU Leuven, but he became the President of the Technical Committee of the Proeftuin in Herent, and as such, had access to grondwitloof farmers. It was a role he held for 10 years, and one which he believed would establish a good connection with the growers: “To listen to the growers and what they want,” he says of his objectives. “What their problems are. How we can deal with it.”

During his project, he collected a substantial amount of seeds, in the range of 300 growers’ selection lines. But the funds from the University quickly ran out. De Proft contacted the Ministry of Agriculture, who declined to continue with funding. “I stopped doing it,” he says. “But I had the collection.”

After De Proft had collected the seeds, he felt the seedbank was too valuable a resource not to use for research. In particular, he wanted to undertake characterisation work on the Belgian endive, essentially developing a map which would link DNA present in the growers’ selection lines to certain characteristics: sensitivity to mould or browning, shape and size, drought resistance, tightness of torpedo etc. If he could identify characteristics, he could show the farmers how their methods were impacting on the development of these characteristics and down the line, he might be able to crossbreed to attain Belgian endive with all the positive characteristics farmers desired.

De Proft began having conversations with the growers about the possibility of characterisation work, research that would involve crossbreeding. But while the growers were generally interested in learning more about the genetic characteristics of their growers’ selection lines, they were not so willing to crossbreed their heritage seeds with that of a fellow grower. De Proft’s frustration was great.

One of the commercial Belgian endive seed breeding companies, Enza, based in the Netherlands, heard about De Proft’s seedbank and expressed an interest in using the collection. Enza wanted to grow them to see whether there was material they could use in some breeding work. “Those collections were sitting there for years and years and somebody was willing to help us out,” says De Proft, aware of Enza’s commercial intentions but also confident that they might give him the opportunity to carry out important work which he believed would benefit growers of Belgian endive. “I offered them. Otherwise, they will stand here for years and nothing will happen.”

In return, Enza supported De Proft’s research project to develop DNA maps of the Belgian endive. Maurice De Proft did not sell the seeds, but the exchange resulted in Enza partially funding KU Leuven’s DNA characterisation work in witloof, including funding for several PhD results related to the research. Enza would use this characterisation model to breed lines and obtain hybrid seeds which boasted the genetic characteristics that they wanted, seeds that would have been sold to growers for use in the production of hydrowitloof and Brabants grondwitloof.

Given his close proximity to the grondwitloof farmers in his role as President of the Technical Committee of the Proeftuin in Herent, De Proft had already seen in the 1980s that the only way for Belgian endive to survive was if growers put an end to the political infighting and began sharing everything with everyone. “That’s basically the philosophy of science,” he says. “I wanted to get them involved as much as I could and to explain to them all the results, and explain to them in detail what we did and how they can profit from it. But to understand this clearly, you must have a certain education in science. In the 80s, I’m sorry, but that was not possible.”

For De Proft, the growers, through what he describes as “protectionism”, were perpetuating their own demise and consequently, the death of grondwitloof. He believed that the donation of seeds was an investment on their part in research which would improve the cultivation of witloof for their benefit. For many of the Brussels grondwitloof farmers, they had been betrayed, their precious heritage seeds given away to the enemy. Growers like Jan Pasteels and Ingrid Dockx felt that their livelihoods had been jeopardised and their heritage disrespected.

At the beginning of 2019, before they set out on the project, neither Bram Van den Poel nor Yannah Cornelis were aware of De Proft’s previous collection. But many of the farmers had not forgotten that the heritage seeds they had given to KU Leuven for De Proft’s seedbank had been transferred to Enza.

Van de Poel contacted Enza, who informed him that they didn’t have any documentation about the collection anymore. “It’s sitting there but nobody knows what tube is which lines,” says Van de Poel. “So then the collection becomes, let’s say, it’s not very valuable anymore.”

Unless Van de Poel could convince the farmers that KU Leuven and the Proeftuin would never give away their heritage seeds to a third party, it would be very difficult to convince grondwitloof growers to contribute and the project might be dead in the water. Much worse, the last few hundred growers’ selection lines in existence amongst Brussels grondwitloof farmers, decreasing in number dramatically year on year, would be lost forever. Not only would a huge part of Belgian agricultural and culinary heritage be lost, but there would be no growers’ selection lines available to start off again, even if there was someone to do it.

Bram Van de Poel went back and spoke to some of the farmers, as well as to a legal team at the University. “This time we’ll have to make sure it does not happen,” he says. What they came up with was a contract that KU Leuven and the Proeftuin would enter into with the farmers. In essence, the contract did two things. Firstly, it stated that Brussels grondwitloof farmers who donated their growers’ selection lines to the seedbank would be able at any time, in case they were experiencing difficulties on their farm, to ask for samples of their seeds. Secondly, it stated that the seedbank was specifically for the purposes of preservation and prohibited KU Leuven and the Proeftuin from giving away the seed collection to any third party.

After putting the contract in place, growers of Brussels grondwitloof were more open to a discussion about giving their heritage seeds to the project. Donations started coming in and Cornelis began processing. At the end of the project, Yannah Cornelis and Bram Van de Poel had managed to collect 504 different growers’ selection lines. Despite the funding coming to an end, Cornelis is still collecting today, as growers continue to participate and bring in their seeds. “I was very happy with that result,” says Van de Poel. “Because there aren’t that many farmers anymore that use their growers’ selection lines.”

The heritage grondwitloof seeds of the Hof De Soete farm will never be a part of that collection. Jan Pasteels and Ingrid Dockx, among other growers, never signed that contract. Their growers’ selection lines will die with the farm, when they both retire in a few years. Their two daughters, aged 37 and 38, have pursued other careers unrelated to the growing of grondwitloof—“Which I can understand,” says Pasteels. “Witloof is something of the past. It’s gone.”

Pasteels was sceptical about the contract option. “Who’s gonna control it?” he asks. “We don’t see what’s happening at the university or anywhere else. We don’t know what’s happening with the seed.”

Pasteels also believes that because of climate change, the heritage seeds they intended to bank would be worthless in just a few years. “If they keep it for 20 years, the seeds of then won’t be usable in those years,” says Pasteels. “The plant won’t feed for the climate that is happening at that time.”

In his eyes, the only parties set to benefit from the project are large seed companies who could use the rich genetic material of the heritage seed collection to produce products for hydroponic cultivated witloof and Brabants grondwitloof, both of whose growers use hybrid seeds, and both of whom are his competitors. “I don’t think Yannah and Bram are to blame,” says Pasteels. “I think they have been used. Why should we help our concurrents? Our goal should be that the Brabants grondwitloof farmers are changing and going back to Brussels grondwitloof. But they’re not gonna do that because it’s a damn lot of work. We’re not gonna help them to survive. We have to survive ourselves.”

De Proft takes a logical, unromantic approach to the survival chances of grondwitloof befitting of his scientific disposition. “If Belgian endive disappears, who cares?” asks De Proft. “People of 50 and older. The younger people don’t care. In the 1920s and 1930s, we had a car company in Belgium called Minerva. They were competing with Rolls Royce at that time. Do you see any Minerva around now? Yes, you see some in a museum. There you see a Minerva. It’s the same thing.”

The scientists understand Pasteels’ cynicism, but argue that it is precisely for the reasons he mentions that farmers should share their seeds. Yannah Cornelis plans to sow a selection of the seeds in the fields of the Proeftuin every year, and later force them in the soil so these heritage seeds can adapt to the changing climate. In this way, she can try to ensure the collection remains valuable. “It’s just an extra argument to give the seeds to make sure the scientists have a better background population,” says Van de Poel. “Having a lot of biological diversity gives you a much stronger chance of finding or creating new lines in the future that will be able to tolerate climate change.”

Earlier this year, the Nationale Proeftuin Voor Witloof changed its name. No longer is there a reference to Belgian endive in its title. It’s now the Praktijkpunt Landbouw Vlaams-Brabant: the Practical Centre for Agriculture in Flemish Brabant. Yannah Cornelis is still employed there, working hard on witloof projects, currently on one to study maximising quality parameters of Belgian endive at different phases: in the field; storage of the root; and during forcing. Cornelis is in contact with a group of people planning to revive the defunct Witloof museum, with a possible reopening at a different location, a potential new shrine to the heritage of Belgian endive. Van de Poel is working with her on some of her projects, more optimistic about Belgian endive than most people after meeting some young and ambitious farmers, as well as younger researchers like Yannah Cornelis.

It seems likely, however, that there will be no growers of Brussels grondwitloof within twenty years from now. If some still do exist, their grondwitloof will be available to buy in tiny quantities and only at very high prices, perhaps served exclusively as rare delicacies in expensive Belgian restaurants. Perhaps some growers of hydroponic cultivated witloof will still be around, although dramatically less than now, those that can afford to renew their aging hydroponic equipment and maybe consolidate with other farms to streamline efficiencies in the face of plummeting prices and an ever-increasing array of vegetable alternatives in supermarkets.

If Brussels grondwitloof does completely disappear in the next few years, at least there are grondwitloof heritage seeds, sitting in liquid nitrogen at temperatures of -196°C in chambers owned by Bioversity International at the KU Leuven, 504 diverse growers’ selection lines in total. For future agriculturalists, scientists, farmers, and traders, they will represent a time capsule into Belgian’s past. Perhaps one day, those involved might agree on how those seeds should be used.

*