For the last forty years, Leroy Breweries’ ale “Poperings Hommelbier” has symbolised the link between brewing and agriculture in Belgium’s main hop growing region of the Westhoek. Why has it resonated so much with people in the region? And is it really the one and only beer that best represents the Westhoek?

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

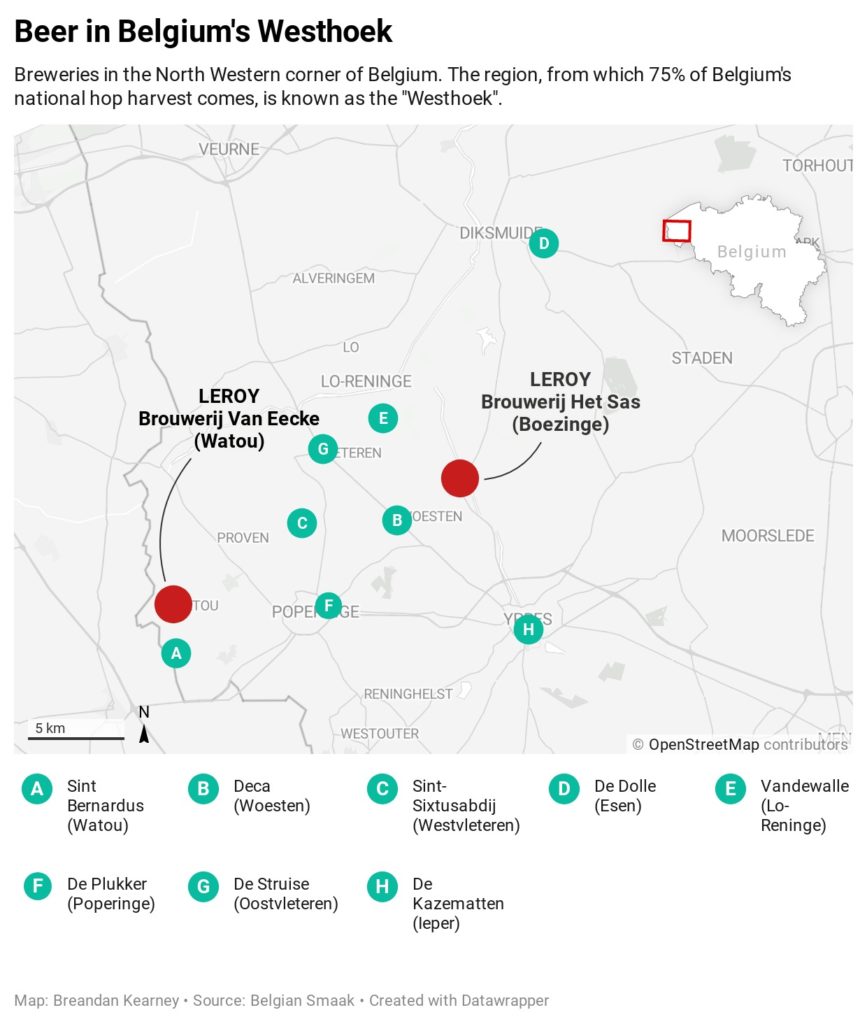

The cities of Poperinge and Ieper are located in the north western reaches of Belgium in a region known as the Westhoek (“hoek” means “corner”). It’s a place with a diverse range of breweries: think, among others, Trappist Westvleteren, De Struise, Kazematten, Deca, St. Bernardus, Vandewalle, and De Plukker. The two cities enjoy a friendly rivalry dating back to the 14th century when politics forced a division of commercial activities. Ieper were exclusively permitted by authorities to work in the lucrative industry of linen production. Looking for alternatives, the inhabitants of Poperinge took to hop farming, even though it offered less opportunity for wealth. Neither city has forgotten the story.

During one civic reception at the newly opened Hop Museum in Poperinge in 1979, it was pointed out by an attendee that the beer being served to visiting dignitaries—an ale called Ypra from Brouwerij Vermeulen—was from Ieper and not from Poperinge.

In their most sacred institution—the Hop Museum—Poperingers were serving beer made by the enemy. The city authorities vowed to create a Poperinge beer.

There was no brewery in Poperinge. The closest was the Trappist brewery at the Sint-Sixtus Abbey in Westvleteren, but the monks would not entertain a commercial collaboration. The next closest brewery was Brouwerij Van Eecke in the village of Watou, less than 10 kilometres from Poperinge. When asked if they would create a beer with the city, the Leroy family who owned Van Eecke immediately said yes. In order to plan and launch the new Poperinge beer, a small committee was formed in 1980 which included city officials, restaurant owners, and the Leroy brewery engineers and brewers from Van Eecke. The instructions from the committee were clear: a blond, easy drinking beer, higher in alcohol than a regular pilsner, and one showcasing the hop culture of the region. The committee tasted the Van Eecke trials across several sessions, eventually arriving at consensus.

The beer would be launched at the Poperinge Hop and Beer Festival in 1981, a huge festival in the region, held once every three years where visitors from other hop growing countries such as Germany, Czechia, and the UK were welcomed.

In August of 1981, a few weeks before the Festival, the city of Poperinge held a press conference to launch the new beer. It would be a Belgian Strong Golden Ale of 7.5% ABV with a fermentation profile reminiscent of black pepper, cumin, zesty orange, and ripe pears, with notes of honey deriving from both its malt and yeast.

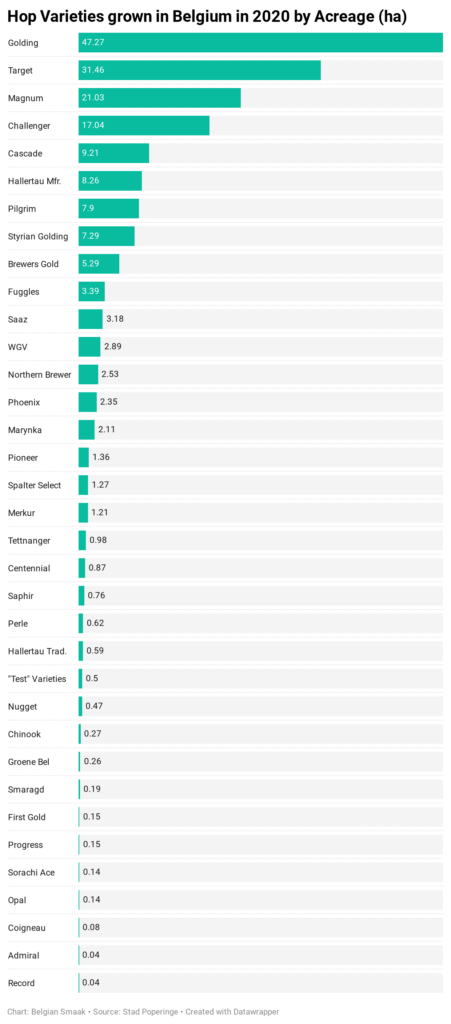

Most importantly, it would showcase hops grown around Poperinge—the varieties a “secret, but all from Poperinge” in the words of the Leroys—in its earthy, almost grassy, hop aroma and flavour.

They would call it “Poperings Hommelbier”, using the name of the city in the branding as well as the local dialect word “hommel” which means “hop”. The officials of Poperinge wanted it to be a beer of which the city inhabitants would be proud. The Leroy family just hoped that enough people at the Festival would try it so they could sell most of the batch they had brewed. They had no idea then that by the beginning of 2020, it would still be regularly brewed, on its way to becoming the brewery’s most important beer.

Thirty-nine years after that launch, on Wednesday 11 March 2020, brothers Bruno Leroy and Karel Leroy found out that the bars in Belgium had been ordered to shut two days later, at midnight, due to government measures relating to the Covid-19 pandemic. Leroy Breweries owned thirty cafés in the Westhoek and all of those cafés would have to be closed, meaning that no Leroy beer could be sold through them. They would be immediately losing an important distribution channel in their home market.

However, Leroy Breweries operated two facilities at two different sites, both of which were close to the French-Belgian border (Brouwerij Van Eecke in Watou, and Brouwerij Het Sas in Boezinge). The proximity of both breweries to France, with its large population and growing interest in beer, made it an important market for Brouwerij Leroy. The French cafés were still open. As long as France didn’t close down, they might be able to maintain sales there and keep their business afloat.

In 2020, before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, Hommelbier was competing with Leroy’s SAS Premium Pils (5% ABV) to be the brewery’s most important beer. Leroy also produced a number of “legacy” products at the Boezinge facility which had been in their portfolio for decades, including low-alcohol Table Beers which in previous generations were popular as an accompaniment to family meals. Now, with the Lockdown, the future of all of their brands was uncertain.

Then, just a few days after the Belgian Lockdown was announced, the French government made an announcement. At the end of the week, at midnight on Saturday 14 March 2020, all bars, restaurants and cafés, as well as all non-essential services, were being ordered closed until further notice due to Covid-19. In just three days, Leroy Breweries lost 85% of its revenue. “That was a panic,” says Bruno Leroy. “Our two biggest markets closed.”

Like breweries and other businesses all around the world, Leroy Breweries—the second oldest independent family brewing company in Belgium—were forced to scramble for their survival.

Bruno and his brother Karel are the eleventh generation of the Leroys to make and sell beer in the Westhoek. The family business started in 1572 at the Lock in Boezinge, a short section of the village’s canal used for raising and lowering boats with gates at each end which could be opened or closed to change the water level. The Dutch word for “Lock” is “Sas”, and the brewery that was born there became known as Brouwerij Het Sas. Brouwerij Van Eecke opened in 1624 as a castle brewery for the Count of Watou. The Leroy family bought Van Eecke in 1962 and in 2016 combined it in one company with Het Sas. They named the new company “Leroy Breweries”.

The mild maritime climate and fertile soil in the Westhoek have traditionally been ideal for growing hops. Hops are the flowers of the hop plant Humulus Lupulus, used as a bittering, flavouring, and stability agent in beer, with the ability to impart floral, fruity, or citrus flavours and aromas. Hops are vigorous climbers, trained to grow up bines which are most commonly harvested in Belgium in September. They are one of the main ingredients of almost every beer.

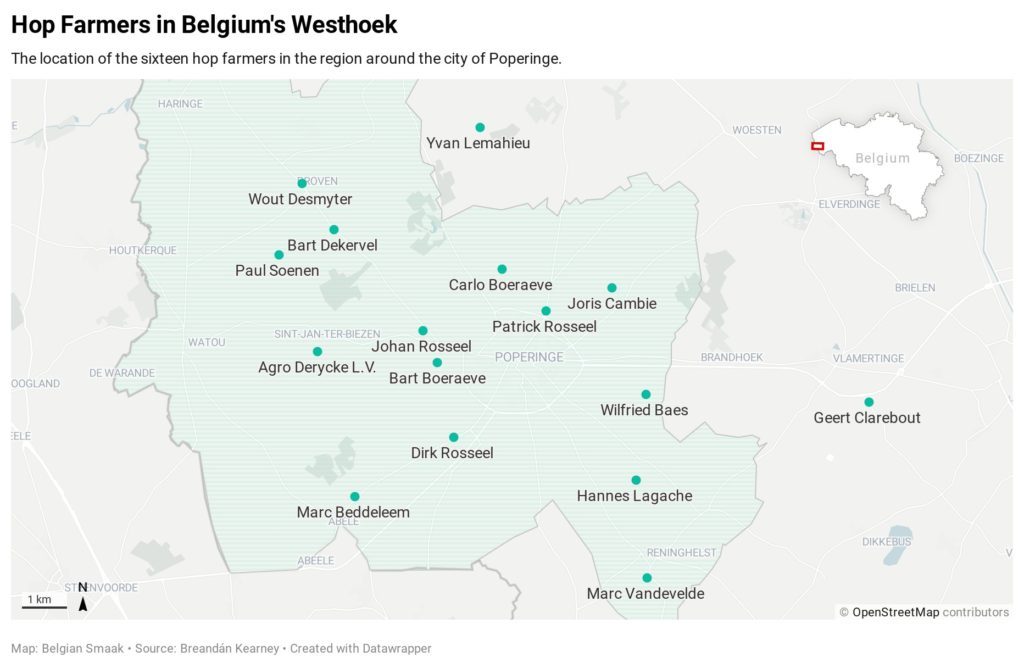

There are thirty five hop growers in Belgium, cultivating 184 hectares of hops: 25 hectares in Wallonia and 159 hectares in Flanders. Of those cultivated in Flanders, 136 hectares are grown around the outskirts of the city of Poperinge by a tight-knit community of sixteen hops growers. In short, hop growers in Poperinge deliver three quarters of the country’s hops.

Leroy Breweries began producing different iterations of the Hommelbier: a dry-hopped version, with additions post fermentation of varieties grown around Poperinge, giving an additional hint of green grass and spring flowers; and a Fresh Hop version, where the hops used were added within hours of being picked on the farm, delivering a less edgy bitterness. “You have not been in Poperinge if you did not taste a Poperings Hommelbier,” says Luc Dequidt, Head of Tourism in Poperinge between 1983 and 2013. “It’s something 100% true blood Poperinge. With all due respect for the other breweries and the other beers, the Poperinge beer is the Hommelbier.”

So when the tri-annual Hop and Beer Festival in Poperinge, due to take place on the weekend of 18-20 September 2020, was cancelled in April of this year, and with specialty bars and export markets still closed, Poperings Hommelbier was facing a huge distribution challenge. With Leroy’s own cafés forced shut and with France still closed, sales of their SAS Pils had dramatically decreased.

Top Right: A Westhoek local does some gardening in the hoodie of the local brewery.

Bottom: Karel Leroy amidst the lagering vessel manholes at Het Sas brewery in Boezinge.

Bruno Leroy, twenty-six years old, had grown up in the brewery, but hadn’t officially started working there until 4 November 2019. His ambition for the next years was to ensure widespread distribution of Poperings Hommelbier into more retail and trade channels in Belgium, as well as more export markets internationally. But his focus at the beginning of 2020, just a few months into his employment with the family brewery, was helping to save it from financial ruin.

Bruno and Karel, together with their father Philip, decided that they could manage financially for several weeks if they put all 30 full-time brewery staff—with the exception of three or four key personnel—on a temporary unemployment scheme related to Covid-19 which was being offered by the Belgian government. Karel Leroy, thirty years-old, managed production and would remain working with his father on issues relating to logistics and planning around Covid-19 matters. Bruno Leroy was working in sales and marketing, and with all his projects set to be cancelled—beach bar themed events and branded activities at the well-known Dranouter folk festival nearby—he was sent on temporary unemployment. It was a measure Bruno understood.

The Leroy family decided to compensate the tenants who managed their bars by forgiving the rent on their café properties for the entire month of April 2020. They also pledged to give a keg for free when they reopened. “Some bars really needed it,” says Bruno Leroy. “It’s a bit of help from our part.” It was a financial risk for Leroy Breweries, but they hoped that the action would show their support, and help the café tenants come out of the Lockdown in better shape.

On 28 May 2020, the French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe announced the reopening of bars and restaurants nationally, but with limitations on numbers and restrictions on the distances people could travel. A similar announcement followed a week later from the Belgian Prime Minister Sophie Wilmès, with bars and restaurants in Belgium reopening in a limited capacity from 8 June 2020.

Bruno Leroy began working again at his family’s brewery, four days a week, promoting beer into the French market and into certain Belgian retail channels that were open. What he noticed looking at the invoicing figures over the previous three months was that the sales of all of Leroy’s beers had decreased dramatically, except for two.

While SAS Pils and Hommelbier had experienced a drop in sales of between 80 and 85%, Bock Leroy and Bruin Leroy—their simple, unsexy, low-alcohol Table Beers—had not only held steady in sales figures, but they’d actually experienced a small increase in sales of 3% during the pandemic. Bruno wondered why they had held true while Hommelbier had suffered? Why had the people of the Westhoek turned to Table Beer in their most challenging time?

Elien Rosseel is small-framed with long nut-brown hair, and she wears eyeglasses with large rounded frames. She speaks with one of those broad Poperings dialects that Dutch speakers outside the Westhoek struggle to understand, as if always with a hot potato in her mouth, her speech patterns direct and to-the-point. She combines working in her own family’s hop fields on the Watouseweg with her job as an agricultural consultant for Stad Poperinge. In Elien Rosseel’s family kitchen, it’s Leroy’s Table Beers that show up most regularly, shared at lunch-time between her mother Annick, her sister Valentine, her father Johan, and her brother Michiel. “My father and brother still drink Table Beer every day,” says Elien. “Every single day.”

The “Tafelbiers” or Table Beers produced by Leroy are sweet, low-alcohol ales which in the 1920s were commonly enjoyed by Belgian children and their parents at the dinner table in the place of sugary soft drinks or unfiltered water. Bock Leroy was blonde. Bruin Leroy was brown. Both were 1.8% alcohol by volume. “Many older Belgians remember with affection how they were introduced to beer by their parents over Sunday lunch, with a glass of tafelbier, poured from a genuine beer bottle,” writes Tim Webb in the Garrett Oliver-edited Oxford Companion to Beer. On the beer rating site Untappd, User Michaël “Maïki” V describes the Bruin Leroy as “a classic”. User Yves M. says it’s “meat stew beer without meat stew”. And Richard B, of the Bock Leroy, says: “It’s terrible, but it’s tradition.”

Breweries in Belgium have largely abandoned Table Beer, but because there was still demand in the Westhoek, Leroy persisted with production and are now one of a handful of breweries with a market share in the category. The Westhoek is a region where traditions die hard, well suited to a beer now mostly consumed by elderly drinkers reminiscing for their youth, or utilised in the kitchens of families making sauces and stews. Where once Table Beer seemed to be a staple of Belgian family life, always there in the background, no big flavours to interrupt the important events of the day, it is now mostly thought to be an irrelevance. The Leroy family had considered on several occasions to lose Table Beer from their portfolio. But they vowed among themselves only to do that if the people of the Westhoek stopped buying it.

Not only were families such as the Rosseels buying more Table Beer as they spent more time together in their homes during the Lockdown—Leroy delivered to individual houses and community centres even before Covid-19—but hospitals and care homes were ordering more.

Patients at the Jan Yperman Hospital in Ieper, many of whom were from an older generation, and all of whom were unable to receive visitors during Lockdown, opened an extra bottle of low alcohol Table Beer in the evenings to get through the pandemic. “The first thing we want people to do here is that they heal,” says Pieter-Jan Breyne, Communications Manager at the hospital. “That’s physically, but also mentally. We try to make food that they like, and beverages that they like. So if that’s a Table Beer for some, why not? If that reminds them when they were younger, ok. Table Beer won’t heal them, but it’s a small part of making them feel better.”

Because a lot of people were unable to leave their homes during the pandemic, the demand for pre-made meals to heat up at home had also increased significantly. Catering businesses needing to make a lot more sauce and stew dishes with beer began reporting to Bruno Leroy that they had started to see problems with the Table Beer brands from other breweries around Belgium that they were using. “Their sauce didn’t thicken,” says Bruno Leroy. “So we got calls from companies that make those pre-made meals.”

Table Beers and hop farming offer someone like Elien Rosseel the chance to openly live her regional pride. For a similar reason, she took part in the Hop Queen election at the Poperinge Hop and Beer Festival, a kind of agricultural show meets beauty contest. Six years ago, when she was 20-years-old, Elien Rosseel and her two competitors—Laura De Ganck and Axelle van Bruwaene—were subjected to a series of exams behind closed doors on the afternoon before the election results. One element of the exam was hop picking. Another was a blind beer tasting during which the Poperings Hommelbier from Leroy came up. When the results of the Hop Queen election were announced on Saturday night, 20 September 2014, in the marquee tent in front of a packed crowd of 3,000 people, Axelle van Bruwaene was crowned the Hop Queen, winning an all-expenses paid trip to New York and the honour of being introduced around the city for the rest of her life as a Hop Queen.

Despite losing, Elien Rosseel is realising the dream of representing her city in a different way today, through her work for Stad Poperinge as a conduit between the city and its hop farmers. The initiatives in which she’s involved—even if her role is less high-profile than that of a Hop Queen—make her an effective ambassador for the region and demonstrate why the hop industry is likely to dominate the cultural identity of the Westhoek in the future.

The cancelled 2020 edition of the tri-annual Poperinge Hop and Beer Festival has been rescheduled to take place in September 2021. The city is waiting to celebrate its hop farmers again. It longs for a new Hop Queen. It looks hopefully to its next harvest.

Part of the future of the hop in the Westhoek is about communicating its very existence to consumers. Elien Rosseel worked with several government agencies to develop a mark which could be added by breweries to labels of beers which used Belgian hops in their beer. Batches of hops came with a serial number, and breweries could submit that serial number with information about the beer for permission to use the mark. Elien maintains the roster, but won’t share details due to agreements with the breweries relating to privacy. The mark is designed to appeal especially to Belgian drinkers who are proud of their hop growers. Almost immediately, Leroy Breweries adopted the Belgian Hop logo on the labels of Poperings Hommelbier. Today, a total of 58 breweries in Belgium use the seal on 214 different beers.

Poperinge hop farmers, self-admittedly stubborn, are well suited in character to be part of this future. Many have already changed their entire business after breweries stopped demanding the varieties of bittering hops which took up most of their crop, and started demanding aroma hops. “It takes three to four years to change over your hop plants,” says Carlo Boevaerts, hop farmer on the Sint-Sixtusstraat in Poperinge. Climate change has resulted in periods of drought in the summer and wild storms in the winter, many of which have ripped down hop vines and destroyed annual yields. In August of this year, for the second time in three years, a storm completely destroyed one of the hop fields of Poperinge grower Joris Cambie. “Mother Nature 2 – Hop Farm 0,” wrote Cambie in a tweet.

Fortunately, the Westhoek recently received a European grant as part of a rural development program to preserve the Belgian hop area and help further promote the purchase of Belgian hops by Belgian breweries. Some of those funds are earmarked for developing the Westhoek’s very own hop variety, one which Elien Rosseel says might reflect the characteristics of old Belgian hop varieties which have all but disappeared.

Importantly, Leroy’s Hommelbier is experiencing an encouraging comeback as Belgians adjust to Covid-19 restrictions, with Bruno Leroy’s vision for it to become his family’s most important beer a realistic goal in his tenure.

But just as it did during the pandemic, Table Beer seems set to be part of that future too. The Westhoek is a rural region, where family is the constant and where traditions die hard. For elderly people who grew up drinking Table Beer as children, and for farming families accustomed to sharing a bottle of Table Beer at meal time, it represents a comfort, a staple of everyday life, that which hath been is that which shall be. There was nothing fancy about it. But that was the point. Amidst the infections, and the deaths, and the restrictions, people were desperate for some sense of normality.

During the Lockdown, Elien Rosseel cocooned with her family on their hop farm in Poperinge where Johan Rosseel and Michiel Rosseel drank Table Beer every day. They poured a glass of sweet, blonde, low alcohol Bock Leroy from a small 25cl bottle, as normal to them as eating bread, a comfort after working among their hop bines. As long as they keep drinking it, Leroy Breweries will keep making it.

*