In 2020, three young Belgians started a brewery with an ambition to cohesively merge their widely diverging beer tastes—pastoral Belgian ales, traditional English styles, and mixed fermentation beers packed with fruit. They’d have to do it against a challenging backdrop: disinterest from Brussels drinkers in unfamiliar styles, rolling pandemic lock-downs, the fracturing of their original triumvirate, a global energy crisis, and an increasingly cut-throat beer market. In Belgian beer, it’s survival of the fittest: you live by the law of the jungle.

Words by Breandán Kearney

Photography by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Eoghan Walsh

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “New Arrivals” series.

I.

Welcome to the Jungle

Christophe Bravin first watched the 1972 American thriller Deliverance in the late 2000s while he was studying Cinematography at INRACI technical school in the Forest district of Brussels.

In the film, four businessmen decide to canoe down a river in the remote northern Georgia wilderness before it is dammed. Bravin compares the story of Deliverance to the journey of Brasserie La Jungle, the small Brussels brewery he opened in March 2020 with two of his friends, Félix Damien and Martin Pirenne. “We were living in the city and we wanted to take a wild nature break,” says Bravin.

La Jungle started out at Hangar du Kanaal, a co-working space that has since closed down. Today, their home is Studio Citygate, a complex of old textile warehouses on the border of the Cureghem and Biestebroeck districts in Brussels’ Anderlecht region. These warehouses were abandoned for decades but are today given over to creatives, entrepreneurs, and associations as part of an urban renewal project. It’s located a few hundred metres from the city’s Senne river to the east, and a few hundred metres from the Brussels-Charleroi canal to the west.

Outside Studio Citygate are Moroccan bakeries, Romanian cafés, and traffic jams. Inside Studio Citygate, La Jungle’s tiny, windowless production space has for company a diverse range of neighbouring businesses: a skate park, a climbing hall, a music centre, a chocolatier, a jewellery designer, a blacksmith, a book binder, a ceramic potter, and a bicycle shop.

The brewery was named for the chaotic urban jungle that surrounds it; a chaos Bravin, Damien, and Pirenne loved but from which they also aspired to be free. Their philosophy was to bring pastoral beers—Belgian Saison, in particular—to their urban home, as a form of self-rescue; a deliverance of their own.

If there’s a lesson in Deliverance—a film which features a brutal depiction of a sodomous rape, canoe accidents, gun shootings, duelling banjos, and intense physical hardship—it’s delivered by Burt Reynolds’ character Lewis Medlock: “Sometimes you have to lose yourself ‘fore you can find anything.”

It’s a philosophy Bravin and his partners have learned to appreciate in the three and a half years they’ve spent navigating their own canoe in the choppy waters of the Belgian beer market. According to Bravin: “When you go down the river in the canoe, things are not always as pleasant as you first thought.”

II.

Transatlantic Flight

Félix Damien met Martin Pirenne at the Lycée Martin V High School in Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve. Christophe Bravin met Pirenne playing football for nearby FC Limelette. Bravin and Pirenne went on to study together at INRACI, the National Institute of Radioelectricity and Cinematography in Forest. At the same time, Damien studied Industrial and Agronomic Engineering at La Haute École Charlemagne.

The trio would drink beer and watch cult American movies from the 1990s and 2000s: movies like Michael Mann’s Heat, Joel Schumacher’s Phone Booth, Quentin Taratino’s Pulp Fiction, and The Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski. Pirenne says that the 1972 documentary Week-end ou la qualité de la vie inspired a lot of beer names, a film by Jean-Jacques Péché, who taught Pirenne and Bravin at INRACI, which followed a civil servant and his family for a weekend on the Belgian coast (the civil servant, Michel Demaret would go on to become Mayor of Brussels). As did Quality of Life, a 2004 drama about the story of two graffiti writers in the Mission District of San Francisco. And then of course, there was John Boorman’s Deliverance.

A year into their studies, a new brewery opened in Brussels: Brasserie De La Senne. Its Zinnebir became a firm favourite with the trio. They also loved the dry, bitter, and earthy profile of Brouwerij De Ranke’s XX Bitter. Damien was already interested in wine—his father Vincent Damien owned a wine import business called Fruit De La Passion that specialised in “Vins fous et spirituels” (“crazy and spiritual wines”). But it was discovering the beers of Brasserie Dupont that prompted the three young men to start homebrewing to see if they could create something similar.

They enjoyed it, and shared similiar tastes, so naturally conversation often led them to plans of their own commercial brewery.

But when their studies finished, they each went their own ways.

Christophe Bravin worked as a video editor. Félix Damien undertook microbiological research internships in Valencia, Spain and in Makabana in the Republic of the Congo, before working for a period at Australian brewery Wildflower Blending and Brewing and then at De Ranke. Martin Pirenne pivoted from working with Walloon TV company RTBF to studying brewing science. He first attended the Institut Brassicole du Québec in Canada, before completing a short internship as an assistant brewer at Canadian microbrewery À la Fût, and later following an online course at the KU Leuven in Belgium.

The trio kept in touch. Bravin and Pierenne visited Canada in October 2012 before Bravin himself moved there for a year in 2014. Both Pirenne Damien spent time there across 2017 and 2018.

These Canadian trips and the exposure they afforded to Québec’s vibrant beer scene were formative experiences for the trio. They visited breweries such as Brasserie Harricana and Microbrasserie du Castor, and brewpubs Cheval Blanc and Pit Caribou. They drank at Vice & Versa, a relaxed, wood-trimmed bar which Pirenne describes as the equivalent of Brussels’ beer café Moeder Lambic; a bar in which they fell in love with the Table Beers and Saisons of another Québec brewery, Brasserie Dunham.

The output of a small brewpub in Montréal’s La-Petite-Patrie quarter particularly captured their imagination: Isle de Garde were making English styles: Bitters, Golden Ales, Milds, Brown Ales, and Porters. “Back in Belgium, there was no beer like this,” says Damien. These beers were malty and subtle and sessionable. Their drinkability and nuance appealed to La Jungle’s philosophy of beer as a social lubricant for working people rather than as some sort of elitist drinking experience. “If you compare a porter and a saison, they’re made for workers,” says Bravin. ”The link between the traditional beer is that people want to drink a lot of it,” adds Damien.

When Bravin, Damien, and Pirenne re-united in Brussels to start La Jungle in 2020, they came with brewing experience and a clear vision. The beers they would make would reference the ones they enjoyed drinking at university: Saison Dupont and Bon Voeux from Brasserie Dupont; XX Bitter from Brasserie De Ranke; and Zinnebir from Brasserie De La Senne.

Just like these standard-bearers, La Jungle’s beers would be dry, balanced, and sessionable, brewed without spices, but with European malts and hops only, from Belgium, England, Germany, Slovenia, and Czechia.

Their beers would diverge into two distinct categories. They would brew Saisons, and Grisettes, and Table Beers, some with clean ale yeasts, others with mixed cultures, and maybe with fruit too.

But La Jungle would also attempt to bring English styles of beers to Brussels; those malty beers of nuance and sessionabilty they felt were almost impossible to find in Belgium, and which had wowed them in Québec.

The first category of beers would be relatively uncomplicated. There was one problem with the second, however. Neither Félix Damien, Christophe Bravin, nor Martin Pirenne had ever brewed an English style of beer. Nor had they ever drank in an English pub. Or even visited England. But that wouldn’t stop them; this was just another wild nature break for the trio to navigate.

III.

The Captain’s Table

Brasserie La Jungle is scrappy. Their production space is a tiny windowless lot; their brewing system a relatively primitive 200 litre Braumeister system that feeds 4 CCTs of 6 hectolitres each and 3 plastic cubitainers of 10 hectolitres each. Their brewing water is untreated city water, with minor pH adjustments for optimised mash conversion. “We don’t soften the water in order to keep the carbonate ions for its influence on bitterness,” says Félix Damien.

Their main beer today is Saison La Jungle, a clean, modern Saison of 5.6% ABV that’s light and easy-drinking. Brewed with pilsner malt, wheat malt, and flaked oats, hopped with traditional European varieties, and fermented with lab-grown French Saison Ale yeast, Saison La Jungle is bone dry and fires off orange and tangerine citrus notes alongside pear, apple, and cracked pepper.

The first beer they brewed on their own equipment was their Bière de Table. This was not, however, the table beer of their parents’ and grandparent’s youth. Where they were sweet, brown ales served to children at dinner and now more likely to be found on the gerryiatric wards of regional hospitals, La Jungle’s Bière de Table is a 3.8% ABV beer of mixed fermentation which better resembles a mixed-culture mini-Saison than the brown beers used today as a base for Flemish stew.

It is, Damien says, “a really light and simple Saison.” They brew it with pilsner malt, wheat malt, flaked wheat, and flaked oats, hop it with Styrian Golding and East Kent Golding, and ferment it with the same yeast strain as their other Saisons.

But that’s just the microbial prelude. After primary fermentation, they pitch their “magic blend of wild yeast and bacteria,” a house culture La Jungle has grown from their homebrew days which began as the dregs of bottles of their favourite beers from Cantillon, De Ranke, and Dutch producer Nevel Wild Ales. The beer ferments wild for two months in their plastic cubitainers until the acidity rises and the sugar content drops. They then condition it in bottle for three months so that, according to Damien, “the beer is given time to fully express its wild side.”

The result of all of this is a delicate and slightly acidic beer with a thirst-quenching dryness and a pleasant lemony, lactic-acid profile. To set this “wild” beer—and its successors—apart from La Jungle’s more conventional beers, the brewery turned to illustrator Marie Theurier for their visual identity. If their original labels by street artist Fred Lebbe were high in colour contrast, Theurier’s were more modular, more tussled, more abstract. Lebbe would portray scenes such as a Volkswagen campervan driving down a coastal highway or three figures carrying a kayak along the canal. Theurier’s labels, on the other hand, were based around organics and nature—plants, fruits, and dense imagined forests—all delivered in highly textured and colourful illustration.

After their Bière de Table came a host of other mixed fermentation fruit-inflected Saisons and Table Beers in what became La Jungle’s “Sauvage” range: blood orange; white peach; and red plums. In the way he describes these beers, there is a clear debt in Felix Damien’s approach to the “crazy and spiritual” of his father’s wine business. It was an infleunce that would eventually become more explicit, as they began to think that maybe, one day, they too could do something with grapes.

IV.

Bitter Seeds

In the winter of 2019, Martin Pirenne presented Christophe Bravin and Félix Damien with an English Bitter he had homebrewed. He had been testing out yeast strains, dabbling with Marris Otter barley and some English Crystal malts, and exploring different English hops, particularly Fuggle, East Kent Golding, and Brambling Cross. And he had been trying to homebrew beers with lower—read: English—carbonation levels.

When Pirenne presented the result of his experimentation to Bravin and Damien, they were impressed. “At that time, it was impossible to find an English Bitter in Brussels,” says Damien. It was time for La Jungle to change that.

In preparation, Pirenne organised a tasting of English Bitters for the three of them in a small chalet near the village of Erezée in the Walloon Ardennes. The beers in the tasting included Manchester Bitter from Marble brewery, Don’t Mess with Yorkshire from Northern Monk, and Anspach & Hobday’s Ordinary Bitter. In the spirit of English drinking culture, they tasted in volume—full imperial pints (568mls)—late into the night.

“We woke up the day after, and were like, I’m not sure about Bitter,” says Damien. “Did I understand it?”

“Honestly, it was less clear [to us] the day after the tasting what real Bitter actually is,” says Bravin.

Unperturbed, they ploughed on. They made a beer with Thomas Fawcet malts—Maris Otter, Crystal Light, and oat flakes—and hopped it with Fuggle sourced from an independent hop farm in the UK. They fermented with a London Ale yeast strain. “English Bitter”, as they called the resulting beer, became La Jungle’s first ever keg release. “Everyone will like it,” thought Damien at the time. “It was the first kegs that we were releasing in Belgium,” he says. “So there was lots of excitement behind it.”

But not everyone did like it, and the launch in June 2021 did not go as they had hoped. They were selling the beer to Belgian consumers, most of whom had never heard of English Bitter. And they’d receive complaints from Belgian bars who couldn’t understand why the beer was carbonated to such a low level compared to their other beers. “It was a mistake,” says Damien. “We didn’t communicate enough. People did not always understand what we wanted to do.”

The beer failed to sell out. “We were a bit naive,” Damien says.

Unsure of what to do with the remaining beer, they decided to rack the remainder into an oak barrel and pitch their mixed house culture. Perhaps their wild yeast and bacteria would make an English Bitter more interesting for Belgians.

It wasn’t just the beer’s relative failure which rocked the brewery’s early confidence. Before the launch of the English Bitter, Martin Pirenne had decided to leave Belgium and Brasserie La Jungle.

Canada was calling to him. His girlfriend was studying there and Pirenne felt it would be good for him to go and brew in a different environment. His two brewing partners, he says, understood. “Martin has three loves,” says Damien. “His partner, La Jungle, and Montréal.”

With Pirenne having chosen two of these three loves, Christophe Bravin and Félix Damien were left with a choice: give up on La Jungle. Or double-down, work hard, and make the beers they loved: Belgian Saisons, traditional English beers, and fruit beers of integrity. What they didn’t realise was that things were about to get worse.

V.

The Grape Escape

La Jungle had attracted their own fervent niche following, but by the end of 2021, it was becoming increasingly difficult for Bravin and Damien to make headway in Brussels’ beer market.

Their core on-trade channel—independent bars in Brussels—were more interested in IPAs than session-strength Saisons. “I remember when there was one or two IPAs in a bar,” says Bravin. “And now, I see only IPAs. That’s when we realised the beers we liked are not really represented in the small businesses.”

Add to this the fall-out from the COVID pandemic. La Jungle had launched during rolling COVID lockdowns in 2020, and the hospitality sector had been slow to recover. Belgians were drinking more at home than pre-pandemic, and declining footfall forced bars to make difficult decisions about the number of beers they sold.

Brussels was also no longer the quiet brewing town it was when La Jungle’s founders arrived at the end of the 2000s. There were good breweries popping up everywhere. La Jungle considered most of them colleagues rather than competitors, but they all took up valuable shelf space and tap lines. Cantillon, De La Senne, and Brussels Beer Project had been there first. Then came En Stoemelings, Beerstorming, L’Ermitage, and La Source. Others followed: Brasserie de la Mule, L’Annexe, Arever, Wolf, Brasserie Surréaliste, DRINKDRINK!, Brasserie iLLeGaaL, Mazette, CoHop, and Tipsy Tribe. Brussels drinkers had plenty of local options.

And to make matters even more challenging, the twin impacts of the war in Ukraine on energy prices and a supply chain crisis on the cost of raw materials meant La Jungle’s margins were shrinking.

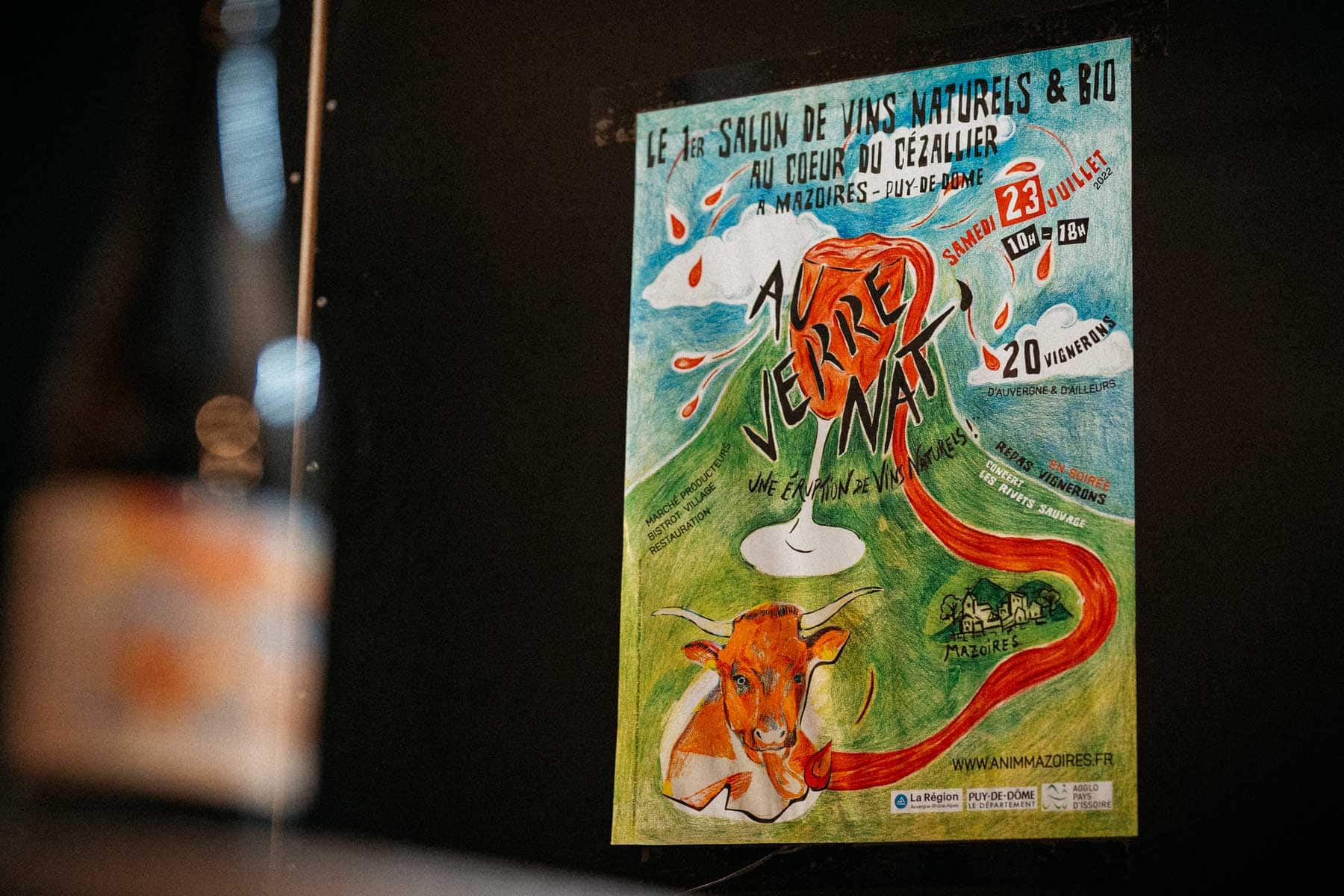

It was in this tumultuous time that the duo were handed what must have looked like a rescue buoy. Through Damien’s father, Vincent Damien, they were invited to pour their beers at a natural wine festival in Auvergne. The festival took place in the village of Mazoires, where Félix Damien had spent summers as a child and where his father Vincent Damien was planning to live in retirement after selling his wine shop. There would be 22 natural wine producers at the inaugural edition of Au Verre Nat, a boutique rural wine festival held in July 2022. There would also be a few breweries, mostly from France. But La Jungle would be one of them.

It was on the Saturday of the festival that Bravin and Damien met Guillaume Noire, a natural wine producer and client of Vincent Damien. Noire was an ex-advertising executive in spirits who had studied winemaking and left Paris for the Loire Valley to make his first vintage in 2017. Noire’s passion was all about organic grapes, healthy harvest, gentle pressing, minimal racking, and long maceration. His organic certified winery used grape varieties such as gamay, gamay fréaux, grolleau noir, grolleau gris, cabernet franc, and chenin.

The brewers and the vigneron struck up a mutal appreciation society. Bravin and Damien loved his wines and Noire loved their beers. “I like their freshness and open minded approach,” says Noire. “They are willing to explore. It’s maybe something in common we have.” They promised to stay in touch.

Inspired by their adventure in France, Christophe Bravin and Félix Damien returned to Belgium with another research expedition already in mind. One that would take them across the Channel, in search of the source of La Jungle’s other great inspiration.

VI.

Crossing the Streams

In March 2023, Damian and Bravin took the Eurostar train from Brussels to London and spent three days drinking traditional English beers in traditional English pubs.

They drank English Bitters and cask Mild at The Harp in Covent Garden, The Ivy House in Newlands, The Stormbird in Camberwell, and the Kings Arms in Bermondsey. They drank Bitter and Brown from Five Points and visited the Kernel brewery on Dockley Rd, Brick brewery in Peckham Rye, and Burning Sky in Firle. In Lewes, just south of London, they enjoyed a tour with Head Brewer Miles Jenner of Harvey’s brewery, the oldest independent brewery in Sussex. “It was super inspiring,” says Damien. “We learned a lot.”

English beer and Belgian beer brewing share, and have always shared, a lot in common: bottle refermentation and cask conditioning; the use of ale yeasts with subtle ester profiles; grassy, tea-like, sometimes woodsy hops. But the two beer drinking cultures are also wildly different: the carbonation levels, the glassware, the alcohol levels, and the table service. One nation’s drinkers nurse chalices for the evening; the other’s enjoy rounds through the night.

Damien and Bravin were initially nervous about immersing themselves in English beer culture precisely because they had been brewing English style beers for three years without ever having visited. But not to worry. “I was kind of happy because I could find a lot of what we brewed in the beer that we drank,” says Damien. “We weren’t totally out of style. We were a bit surprised because Bitters were actually more bitter than we thought, with a bit more astringency.”

Throughout the three days, they talked to producers they visited about cask ale. They learned about the commercial challenges of producing it in the UK. They learned about CAMRA’s quest to safeguard and promote it. And they learned about the care required for its storage and service. When they arrived back to Belgium, Damien and Bravin contacted their keg reseller to enquire about buying some casks.

Despite that early setback with their first attempt at Bitter, La Jungle have persevered with English styles, producing an English Porter and a Brown Ale. “It was not a failure,” says Damien of those first kegs of English Bitter. “Since then, each year, we brew another Bitter. We go deeper into the style. We go darker, more amber-ish, more biscuits. We change the hops. We try to communicate a lot.”

While they were strategising about cask ale, their new winemaker friend in the Loire Valley sent them a gift: plastic containers filled with the pomace of the pressings of grolleau noir and chenin grolleau grapes from his 2022 harvest. Pomace contains the skins, pulp, seeds, and stems of the fruit. Bravin and Damien decided to macerate what was left of their original English Bitter—now a wild beer—on the pomace. Here, three years after the brewery’s foundation, was the first confluence of the three streams that made La Jungle: their obsession with English styles of beers, their penchant for mixed fermentation, and their interest in using natural fruit.

“It was a bit tannic, but the expression of the grape was really nice,” says Damien of the resulting beer. “Not too fruity, but more winey.” After maceration for one month and conditioning for a further nine, they packaged it as Noire Sauvage: a low ABV, very dry, slightly tannic, barrel-aged English Bitter which was malty, rich, and winey. “The tannins that were present at the beginning got more and more smooth,” says Damien of the beer’s evolution. “It gives more mouthfeel and complexity to the beer.”

In July past, Bravin and Damien were back in the Auvergne for the second edition of Au Verre Nat—a place they call their ”second home”. They brought with them the Noire Sauvage so they could taste their beer-wine collaboration with Guillaume Noire. “I was so excited,” says Noire. “Actually, you can really feel they are relatives,” he says of the beer and wine birthed from the same grapes. “Those that liked acidity were kind of surprised,” says Damien of the reaction of festival-goers. “Most of them found [in it] a link with natural wine.”

An experiment based on an accident, Noire Sauvage inspired more beers from La Jungle—Liasis, for example, was their Wild Export Porter, barrel aged with blackberries and blueberries. Had their original experiment with English Bitter not commercially failed so miserably, had they not grown their own mixed culture since homebrewing days, had that invite to the Auvergne never arrived; then Noire Sauvage might never have been and La Jungle may never have found a way to merge their brewing streams. As Burt Reynolds’ character Lewis Medlock said, “Sometimes you have to lose yourself ‘fore you can find anything.”

VII.

Murky Waters

La Jungle’s lease at Studio Citygate ends in September 2024. The organisation who manages the site, Citydev, intend to build a large-scale mixed development which includes houses, a local secondary school, and ateliers. Despite much work, Bravin and Damien haven’t yet secured a new home for La Jungle. Their plan, when they do find a new location—shaped by what Damien describes as “a beer market slowing down and an uncertain global economic situation,”—is to focus specifically on their wild range. Their Saisons and English beers will survive through a series of collaborations with respected breweries that specialise in those styles.

Martin Pirenne now lives in Pointe-Saint-Charles, a neighborhood in the southwest of Montréal. He brews at the Toltek brewpub in Boucherville and is working on a small “fermentery” he will call Mosaiek. “The idea is to make natural ciders, wild beers, and spontaneous beers,” he says. Pirenne was back in Brussels in the summer of 2023, working alongside Bravin and Damien again, this time on a La Jungle x Mosaiek collaboration due for release in early in 2024.

In the meantime, La Jungle’s Saisons have become more honed; their mixed fermentation beers softer; their Sauvage fruit range more expressive.

Their English beers now appear with more Belgian levels of carbonation and a more pronounced hop character. And Pirenne isn’t the only connection they’ve maintained with Canada; they recently brewed a collaboration with the Canadian brewery Isle de Garde that so inspired them back in their Québec days—a narrative-appropriate 4% ABV English Summer Ale called Victoriaville.

They even managed to put out an English Ale named for one of their favourite films. Delivrance is a Golden Ale that gives notes of jasmine, apricot, and orange marmalade, all built on top of a baked biscuit malt character. Its label is a colourful illustration from house artist Fred Lebbe depicting three silhouetted figures on a canoe in the background, lost on a murky, ominous river, a dramatic red and orange sky above them. In the foreground, an arm stretches upwards from the water. But it’s not a shotgun the hand’s grasping, as in the film’s original poster. It’s a bottle of La Jungle beer.

*