Words by Breandán Kearney

Photos by Mark De Bock and Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “War Chest” series. Read more.

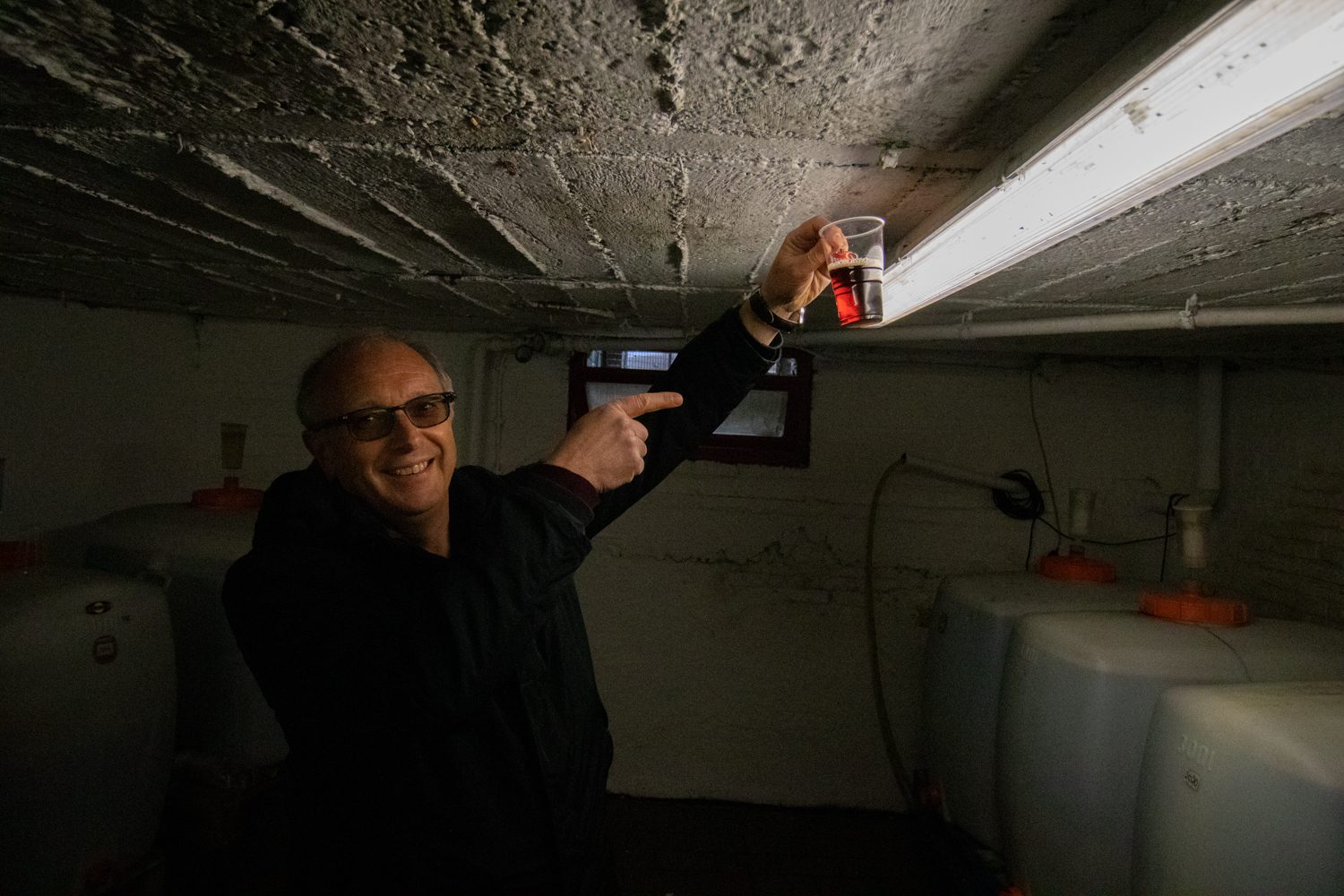

In the municipal cemetery of Saint Eligius Church, thousands of gravestones mark the spots where former villagers now rest in peace. Inhabitants of Eine—Einenaars—claim that the village’s groundwater passes underneath the cemetery and that when it rains, water seeps through the graves and collects nutrients from the dead bodies.This water is used by Brouwerij Cnudde, giving their beers a “special taste”, and explains why they are referred to by locals as “Kerkhofsop”, or “Cemetery Juice”.

Lieven Cnudde, one of the three Cnudde brothers who owns Brouwerij Cnudde, does not dismiss the rumour. “I let them say that,” he says. “The water comes from 12 metres below the surface. It’s possible that some water comes from over there.” When pushed to confirm whether his beers contain the nutrients of Eine’s dead, he smiles: “It’s a circular economy”.

In life, the brewery presence stretches to almost every village occasion: in each of Eine’s cafés; at the annual “Einse Fietel” festival; at civic events during which the brewery serves as a kind of town hall; and at baptisms, weddings, and funerals. In death, then, the Einenaar gives back to the village’s beer, contributing the nutrients of their bones to the glasses of Cnudde which will be enjoyed for years to come by their sons and daughters and nieces and nephews and grandchildren.

Brouwerij Cnudde is as community-focussed an institution as you will find, a relic of the second industrial revolution. Karel-Willem Delrue, who wrote a book about the brewery, uses the Dutch word “volks” to describe Brouwerij Cnudde, saying it is “of the people”. “For the last 100 years, Cnudde has always played a role in all activities, from soccer to the firemen to pigeon sports,” says Delrue. “Whenever there is a community activity in Eine, the bonding fluid is Cnudde.”

Few contemporary breweries in Belgium occupy such a central place at the heart of a village, and in this way, Cnudde offers an insight into Belgian brewing of times gone by. The brewery’s flagship Cnudde Bruin is a brown beer of mixed fermentation with notes of burnt caramel and red fruits, and a dry, mildly acidic finish. It was once described by beer writer Michael Jackson as “an honest, straightforward village beer from less self-conscious times.” The beer’s medium body, slight tartness, and easy-drinking nature render it accessible to the everyman Einenaar, to whom community traditions are king.

The ways in which communities live, work, and interact today—fast-paced, online, and craving massive choice—raise questions about how long a traditional, manually operated brewery such as Brouwerij Cnudde might be able to persist into the future. But in 2021, as breweries in Belgium seek to reconnect with communities in a post-COVID world, they might use Eine as a template for the future.

The symbol of the village of Eine is the bison: a broad, muscular animal with a shaggy coat of long hair which belongs to the bovine family. The most prominent statues of bison in the village are on the bridge over the river Schelde which divides Eine on its left bank from Nederename on its right bank. Two concrete bison stand on each side of the river, four in total, each with its own bronze plaque. The bison symbol comes from something that happened here, at the Ohio Bridge.

During the First World War, the Ohio Army National Guard’s 37th Infantry Division faced the daunting task of crossing the Schelde River at Eine to attack the heavily fortified German “Hindenburg Line”. A sergeant in the 37th Division, Paul Smithhisler of Mount Vernon, Ohio, volunteered for a daring night reconnaissance of enemy lines and swam across the Schelde, alone, under cover of darkness, to sketch diagrams of enemy machine gun nests and artillery positions. Managing to dodge German sentries and patrols, Smithhisler returned with valuable intelligence, and that night, the 37th Division attacked the Germans on the other side of the Schelde.

The operation was a success. On 1 November 1918, the 37th Division crossed the bridge at Eine in what was a crushing blow for the Germans. Ten days later, the First World War came to an end. One of Lieven Cnudde’s friends, Chris De Waele, a former Lieutenant Colonel in the Belgian army, believed that there was more to the Smithhisler story than was known. De Waele had met Lieven Cnudde at a beer quiz in Eine’s Casino café, becoming a lifelong friend of the brewery. He was concerned that the stories of the Americans who had helped save Eine during World War One were not completely appreciated, and De Waele pledged to continue digging into the history to find out what had happened.

The bridge loomed large in his research and in the consciousness of Eine. It had been destroyed and rebuilt multiple times, but after the war, between 1928 and 1930, it was rebuilt as the first prestressed concrete bridge in Belgium. The bridge was donated by the State of Ohio to commemorate the bravery of the 37th Division. The street leading to the centre of Eine is today called Ohio Street and the village’s main square is officially Ohio Square.

The depictions of bisons on the Ohio Bridge in Eine show animals of incredible power, hardwired to protect, head cocked downwards in defence in anticipation of a fight. But Bison have come to be a symbol not only of strength, but of unity, resilience, and community. Recent legislation has installed the North American bison as the new National Mammal of the United States. InterTribal Councils have signed treaties to establish alliances to reestablish bison on their lands. On the verge of extinction in the 1800s, America’s bison now number about 500,000 and live on ranches in all 50 states across parks, refuges, and private conservancies.

Just as bison appear on Ohio Bridge, they have featured on the logo of Brouwerij Cnudde since the brewery’s earliest days. A bison appears on the labels of all their beers and on the glassware of the brewery. There’s a statue of a bison in the garden of the house and brewery on the Fabriekstraat opposite the cemetery where Brouwerij Cnudde is located. The bison is a symbol of your community, and without their Eine tribe, Cnudde would never have survived.

Eine is one of fourteen municipalities in Oudenaarde, a city in the province of East Flanders. Aside from Cnudde, there are three other breweries in the city: Brouwerij Liefmans in Edelare, known for its mixed fermentation Goudenband (now a part of the Duvel Moortgat group); Brouwerij Roman in Mater, the oldest independent family brewery in Belgium; and tiny Brouwerij Smisje. Brouwerij Petre-Devos and Brouwerij Felix were two other well-known producers of mixed fermentation beer in Oudenaarde until they closed in 1970 and 2003 respectively (Petre-Devos has been resurrected since 2015, contracting its beer production outside of Oudenaarde).

Oudenaarde is often referred to in beer literature as the home of Oud Bruin, a beer of mixed fermentation which picks up lactobacillus during its open fermentation, becoming acidified in stainless steel tanks. Indeed, Brouwerij Cnudde has produced no other style of beer during its one hundred year history.

Lieven Cnudde’s great-grandfather Alphonsius Cnudde took over a soap factory on 21 June 1919 and opened a brewery. His oldest son Omer Cnudde took over the business, but in 1944, during the Second World War, Omer died suddenly from heart failure. Louis Cnudde—Lieven Cnudde’s father—was 18 years old when his father Omer died, and he enrolled in brewing engineering classes in Ghent, completing four years of study before returning to Eine to carry on the family brewery.

Louis was a prankster, often dressing up in elaborate costumes and staging publicity stunts. Once he adorned a prison outfit, covered the brewery windows with images of bricks, and arranged for a bailiff to come and arrest him in front of the Eine villagers who had spilled out onto the streets to watch. However, he was also an innovator and during the 1950s, Louis ended the disparate farm activity that was taking place on site and constructed new buildings in which to install upgraded brewing equipment. The machinery he installed then is the same equipment being used today.

Lieven Cnudde and his brothers Steven and Pieter grew up in the house beside the brewery but also in the cafés of Eine such as the Kring, the Pub, and the Casino. Each brother was hard-working, ambitious, and social, but always enjoyed a joke, like their father Louis. “I think it’s something that runs through the blood and passes from generation to generation,” says Karel-Willem Delrue. The brothers would invite the Belgian press to Eine and arranged for fictional Flemish TV sitcom characters to give fake news conferences. Yet despite their joking, and their pursuit of careers outside of brewing, they were always seriously drawn to busy life on the Fabriekstraat. “In a brewery, you see plenty of people that come every day, morning and evening,” says Lieven of the chaotic environment of his youth. “It was never still in this place.”

The brothers also remember that despite their father Louis focussing exclusively on one beer—the Cnudde Bruin—he would dabble in small quantities of cherry beer for his own consumption. The cherries came from the garden in front of their house beside the brewery and were macerated on the Cnudde Bruin. Those memories prompted Lieven to plant cherry trees in the garden of the house where he lives with his family today, one kilometre from the brewery.

The Cnudde brothers remember the 1980s when their father experienced significant issues with his bottling machine, choosing not to invest in a new one after it had broken down. From that day on, Brouwerij Cnudde filled only 30 and 50 Litre kegs and sold their beer exclusively to trade accounts rather than individuals. It meant that Cnudde beers were no longer seen in the homes of Einenaars. But it did strengthen Cnudde’s presence in local cafés.

Louis Cnudde was in his sixties during the mid-1980s when the brewing industry in Belgium began to change significantly. Larger beer companies such as Interbrew began buying up smaller concerns, stripping them for their brands and properties before eventually closing them down. Production became more industrial, with larger quantities produced in fewer facilities. Beer distribution changed, with burgeoning regional and national distribution networks eroding the local delivery runs of village breweries. There seemed to be a continuing shift in tastes, away from acidity and maltiness towards lagers and sweeter ales. All of this threatened to hurt Brouwerij Cnudde in the long-term as a small, hyper-local brewery. As Louis Cnudde was approaching retirement, he made it clear to his sons that he did not want them to continue with the family brewery. He did not want his children to be imprisoned in a hopeless business. “It was forbidden by our father,” says Lieven of a potential handover.

The Cnudde brothers had already established careers for themselves. Lieven was a mathematics teacher and politician. Steven was an engineer. Pieter was a lawyer. But they saw that the brewery they had grown up in was on the verge of disappearing, the same brewery that their parents and grandparents and great grandparents had toiled to keep alive. “It was all of our youth,” says Lieven of the brewery. “It was everything.”

In 1992, it was decision time. The three Cnudde brothers approached their father Louis, and told him they were interested in continuing. Louis was surprised. Before he made a decision about whether to pass everything to his sons, he spoke with the brewers at nearby Brouwerij Roman, most notably to trusted brewing engineers Jef Snauwaert and Marcel Melis who had assisted Louis with technical issues as a neighbouring brewing colleague. They suggested that if Brouwerij Cnudde was to stay small, focus exclusively on local distribution, and not try to compete with large regional breweries, that it might just work as a business. The community of Eine would have to be their North Star. When he returned from the meeting, Louis Cnudde told his three sons to go for it.

On 11 May 1993, Lieven, Steven, and Pieter established a private company called Cnudde bvba in which they all owned an equal share. As a 34 year-old, 33 year- old, and 31 year-old respectively, they would embark on keeping the brewery alive in a part-time capacity, each contributing time dependent on their skillset. The Cnudde brothers decided to brew just three times a year, each batch 5,000 litres, and they would sell their beer only in Eine and Oudenaarde.

To generate funds for the new company, the Cnudde brothers established a partnership with Brouwerij Roman to distribute Roman’s beers locally in Eine along with their own. The partnership strengthened the relationships their father Louis had built up over the years with the neighbouring brewery, allowing the Cnudde brothers to call the experienced brewers at Roman should they need technical assistance. Eventually, they began using yeast which Brouwerij Roman used to ferment its Ename Blond, a top fermenting strain with a medium attenuation that suited the subtle lactic acid bacteria fermentation, as well as mild ester production in line with Oud Bruin’s flavour profile.

The brewery was still alive, albeit with a slightly altered business model, but importantly, its legacy was intact. Lieven’s children Lander and Inge, and Steven’s daughter Charlotte became the fifth generation of Cnuddes to watch their parents brew Oud Bruin in the Fabriekstraat under the shadow of the Eine bison.

As the Cnudde brothers ramped up for production in 1993 and 1994, they had the wisdom of their father on which to rely. His decades of experience were not only invaluable in learning how to produce Oud Bruin in a traditional manner, but the brewing equipment at Brouwerij Cnudde was the same equipment Louis Cnudde had installed as a young man in the 1950s and it required specific know-how to operate.

To produce Cnudde Bruin, the brothers would be using an old copper tun with a mechanical stirring arm to mash the grains, 1,000 kilograms or so of pilsner malt per batch. They’d be boiling the wort in large battered copper kettles, adding 12 kilograms of Northern Brewer hop pellets, and 10 litres of liquid dark candi sugar. They’d cool the beer on a baudelot cooler, on which wort, exposed to the air, runs down the side of a series of pipes filled with cold water. They’d ferment in a large open vat, pitching Brouwerij Roman’s Ename yeast, around 90 litres of liquid yeast per 5,000 litre batch of beer, with the resultant carbon dioxide filling the room to dangerous levels. Their lagering tanks were flat-bottomed repurposed milk tanks placed in a refrigerated room. It was crucial that they have their father on hand to advise them of the system’s ins and outs. But when Louis Cnudde passed away on 22 November 1995, aged 69, the brothers were on their own.

Perhaps it was in seeing Brouwerij Cnudde lose its figurehead, or maybe it was a response to the determination of Louis’ sons, but the community of Eine rallied around. Louis had been a larger-than-life character and the village had loved him. Now they would love his sons. Locals began helping with everything, including brewing.

Danny De Smet had met the Cnuddes in the Casino café because his family had once lived nearby. He took responsibility for loading malt into the malt mill.

Didier Mornie worked in the brewhouse. He began drinking Cnudde beers as a ten-year-old when his own grandfather, Adolf Mornie, a brewer at Cnudde, would take him around the cafés of Eine on deliveries.

Denis De Meyer was a lorry driver who had experience of mechanics and electronics, and on brew days stood at the mash tun, helping to ensure the mechanical arm operated correctly to mash the grains.

Klaus Cnudde, a cousin of the three Cnudde brothers, prepared things in the Casino for the family and volunteers to eat and drink on brew days.

Patty De Craeye and Helmut Malfait toiled in the kitchen. Jan Grypdon and Stefaan Willems assisted in the yard. Filip Loosveldt and Mimi Maes worked at the kettle. Geert Vermeersch offered technical support.

Brouwerij Cnudde was a hive of activity again.

Brew days became parties. Everyone was welcome, so long as they rolled up their sleeves to work. If you helped, you were rewarded with a meal in the Casino and draught pours of Cnudde Bruin into the evening. “You have to deserve your meal at noon,” says Lieven. And so the tribe of Eine came to save the brewery, cementing the social bonds of the community through their shared labour. When they were old enough, the children of the Cnudde brothers would help out too. Now 31 years-old, 29 years-old, and 26 years-old respectively, Lander Cnudde, Inge Cnudde, and Charlotte Cnudde are approaching the age their fathers were when they took over the brewery.

In 2009, the Cnudde brothers started working with another brewery who produced Oud Bruin to bottle their beers: Brouwerij Strubbe in Ichtegem. Up until that point, it had only been possible to drink Cnudde Bruin on draught in a handful of cafés in Eine and Oudenaarde. So that they would be able to sell their beers in small packages to those wanting to pick up a few bottles for home, they made an arrangement with Strubbe. They filled a sterile tank with beer and drove that tank 80 kilometres or so to Ichtegem for filtering, force-carbonating, pasteurising, and bottling. The process meant that not only did Cnudde now have a stable product in small package, but that, for the very first time since Louis Cnudde’s bottling machine had broken down in 1988, Einenaars could drink Cnudde beer in their homes again.

Now that they could sell bottled beer, the Cnudde brothers felt that it was time to release a new beer, a version of the cherry beer that their father had made for his own consumption.

The cherries initially came from the garden in front of the brewery, and when they needed more, they took them from the orchard beside Lieven Cnudde’s house one kilometre away. As demand increased over the years, they started to order sour cherries from the Haspengouw, Belgium’s largest fruit growing region located in the East of Belgium. The cherries needed to be de-stemmed before being used, and so Kriek harvest every year turned into another big party at Brouwerij Cnudde. Friends, family, and locals volunteered to pick the cherries one by one from their stems in the courtyard of the brewery, bottles of Cnudde Bruin served as they worked.

The Cnudde brothers based the new beer on their existing one, macerating 30 kilograms of cherries on 250 litres of Cnudde Bruin, hanging muslin sacks inside plastic fermenting vessels and adding liquid brown sugar to spark a new fermentation. After two years, they had what they described as “Puur Kriek”, the initials of which, “PK”, Lieven jokes also stand for “Horse Power” (“Paardenkrachtt”) in Dutch. Because the PK was so intense—pithy, jammy, and almond-like—they blended it back again, in the ratio of two thirds Cnudde Bruin and one third PK, before packaging. There was no discussion about the name of the new beer. It would be launched under the name “Bison”.

“It’s really admirable what they have created here,” Lieven Cnudde’s son Lander says of his father and two uncles. “It’s part of the story of the village.”

That story—the story of Eine—involves bison and beer and bridges. But the story of the Ohio Bridge still had one major twist: something which would connect the Einenaars once again with the Americans who, one hundred years previously, had saved their village.

Lieven Cnudde’s friend, Chris De Waele, a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the Belgian Army, was still unhappy that the stories of so many of the Americans who had helped save Eine during World War One were being forgotten. He began to dig more into the story of Paul Smithhisler, the 37th Division Sergeant who had swam across the Schelde, and he uncovered something that made him curious: Smithhisler had not embarked on his mission alone.

De Waele discovered that Smithhisler had worked with another American soldier on his secret mission, a Corporal called Frank Burke of Cleveland, Ohio. Burke agreed to wait on the bank of the Schelde for Smithhisler’s return on the night of that undercover mission. When Smithhisler had completed his reconnaissance, he swam back across the Schelde, but the sun was coming up and, seeing a figure moving in the water, the Germans began firing from their side of the River.

Burke was waiting on the Eine bank and helped pull the exhausted Smithhisler up out of the water. The Germans then began firing gas shells at the two American soldiers. Sensing the gas, Burke took out his gas mask but realised immediately that Smithhisler, in a swimming suit, did not have one. So Burke put his gas mask on the face of Smithhisler, who now being able to breath, ran back to camp to give over the drawings. Burke followed after him, but was exposed to the German gas.

That night, the Americans attacked the Germans on the other side of the Schelde with full knowledge of their artillery positions thanks to Smithhisler’s drawings. The actions of Smithhisler and Burke were responsible for defeating the heavily fortified German “Hindenburg Line” and helped to end the war. Paul Smithhisler became an architect in Cleveland, Ohio, and died in 1982 at the age of 93. Frank Burke, however, died in Belgium a few weeks after that mission in Eine in 1918. At first, it was thought that he died of influenza, but later findings showed it was because of the gas. “He died of his burned lungs,” says De Waele.

There are few better lessons in togetherness for the people of Eine than the demonstration of community spirit by the Americans of the 37th Division at Ohio Bridge. And there is no greater lesson in unity for them than the camaraderie shown by Frank Burke to Paul Smithhisler. The stories of Ohio Bridge, and of Brouwerij Cnudde, and of Eine as a place are all the same.

Paul Smithhisler received a Distinguished Service Cross, a Silver Star, and a French Croix de Guerre, but despite the fact that Smithhisler had always referenced his friend’s role, Frank Burke’s part in the mission had never been publicly acknowledged. Chris De Waele wanted to set that right.

Because of his military background, De Waele knew that all soldiers in the 37th Division stationed in Eine would have come from the same State, Ohio, and so he contacted Brian Albrecht of the The Plain Dealer Ohio newspaper, who put together a story which helped unearth members of Frank Burke’s family. From there, De Waele helped organise a commemoration in Eine, during which five members of Paul Smithhisler’s family and five members of Frank Burke’s family flew to Belgium from Ohio to meet one another. De Waele convinced the Mayor of Oudenaarde to pay for ten hotel rooms for the families and to host a commemoration on Ohio Bridge.

On Friday 26 September 2014, the members of both families walked onto the middle of the Ohio Bridge and threw roses into the Schelde River where Paul Smithhisler and Frank Burke had conducted their secret mission. The American Ambassador was there too, as were members of the Belgian and American militaries. Lieven Cnudde was on the bridge in his capacity as elected Councillor for Eine. “Tears and tears,” says De Waele of the intensity of that moment. “It was a special day for the families and for our town. It was very emotional.”

De Waele received a letter from the Governor of Ohio, John Kasich, thanking him for his efforts in organising the commemoration: “The work you have done to make it a reality proves once again that, no matter the passage of time, the bonds of friendship between our nations so long ago will remain strong forever.”

After the short ceremony, the whole party walked the 500 metres from the centre of the Ohio Bridge to Brouwerij Cnudde on the Fabrieksstraat. Suits and military uniforms mingled in the brewery garden and bar. There was an exhibition about Smithhisler and Burke in the Casino café. A marching band wearing feathered hats and white gloves played their brass instruments as a pair of flag pole bearers held aloft an American flag beside a Belgian one. Beers were handed out. The Americans told Lieven Cnudde that it tasted acidic and was very different to what they drank back home.

The bison had been on the bridge. Now they were here on the bottles and glassware and garden. There was nowhere else than Brouwerij Cnudde that such a significant moment could have been commemorated; no other way the dead could be remembered; nothing else they could have been drinking but Cnudde Bruin and Cnudde Bison; every drop filtered through the decomposing bodies of previous generations of Einenaars who, now Cemetery Juice, could contribute once again to this community on the banks of the Schelde.

*