As I enter the grounds of the brewery which produces the Duchesse de Bourgogne beer, I can’t see any signs to tell me where I am.

In fact, nowhere on site is the name of the brewery announced.

Perched between tall green hedges and modest residential buildings and within touching distance of the tiny two-platform village railway station, Brouwerij Verhaeghe mirrors the unassuming character of the sleepy West Flemish community of Vichte.

To locals, it needs no introducing. The brewery has been a part of the village for generations and the Verhaeghes have been brewing on the same spot since Paul Verhaeghe founded the brewery in 1885.

At that time, the brewery had everything it needed within easy reach. It grew and malted its own barley on site, had a good source of water close by, had developed its own yeast culture and could bring hops in from the nearby towns of Poperinge and Aalst.

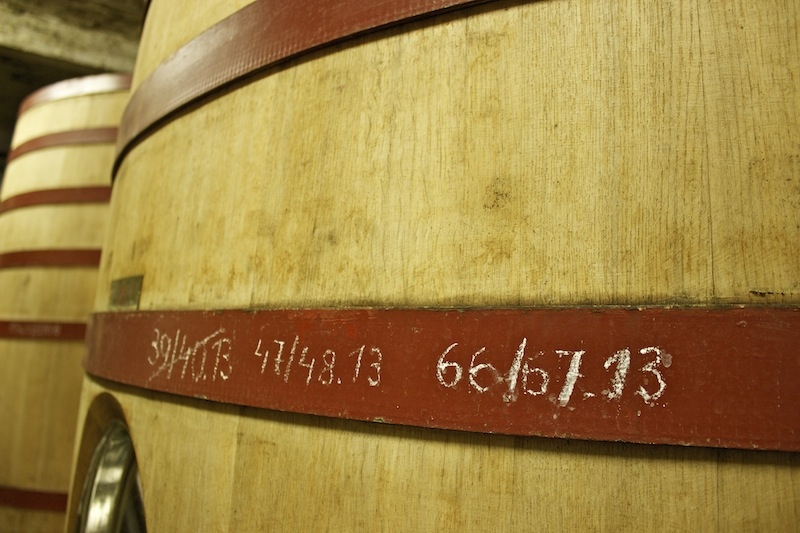

The brewery today still produces the same type of beers that it made when Paul Verhaeghe started brewing. These Flemish red-brown ales are beers of mixed fermentation, a blend of young top-fermented beer with beer which has been spontaneously fermented and matured in upright oak vats.

On this particular day, I’m shooting the breeze with one of the two brothers who owns the brewery, Karl Verhaeghe. His commercial officer, Laurence Delmulle shares a beer with us.

CHALLENGES FOR BELGIAN BREWERIES

The challenges that Verhaeghe have faced are the same as almost all Belgian breweries who were operating at the beginning of the last century. During the first World War, the brewery was completely dismantled by the Germans who used the copper from its brewing equipment to produce ammunition. “The brewery had to start from scratch in 1919. There were 5 or 6 years when we were able to do nothing. We lost all our customers in Brussels and had to build again with our local clientele”, says Karl.

Just as the brewery was beginning to re-establish itself, a new style of beer arrived in Belgium and the Flemish red-brown ales that Verhaeghe and others had produced for years became less fashionable. The brewery was forced to adapt again in the face of the market domination of lager. They invested in new equipment to produce their own bottom-fermented beers. They still brew it to this day, the Verhaeghe Pils, although it accounts for less than 10% of what they produce.

With World War II came another wave of challenges for the remaining Belgian breweries. “The Germans came twice”, says Karl, “to learn how to drink a decent beer”. There’s pragmatism in the Verhaeghe family. And no small measure of humour. Maybe that’s the best coping mechanism.

We follow new trends in the market but more importantly we still brew our beers the same way we did 120 years ago.

Karl points out that “at the beginning of the nineteenth century there were 3,000 breweries in Belgium. Now there are around 120 breweries left”. The decisions that he has taken with his brother to follow the Verhaeghe brewing traditions have been well considered. “We follow new trends in the market but more importantly we still brew our beers the same way we did 120 years ago”.

BREWING DILEMMAS: DUCHESSE DE BOURGOGNE

When Karl and Peter took over from their father, Jacques in 1991, the brewery had enjoyed very few improvements in the preceding years and was suffering from a lack of vision. “In those times the nephew of my father wanted to sell the brewery but my father wanted to continue brewing activity. Investments hadn’t been carried out for many many years,” recalls Karl. “It was an old empty box that we took over.”

We were famous for the old Flemish red-brown ales. That was our strength. We decided to pick that up and keep that going.

The brothers were faced with a dilemma. Should they try to brew a new wave of different products or take on the challenge of a less commercially rewarding but historically more important style of beer? They went for the latter. “We were famous for the old Flemish red-brown ales. That was our strength. We decided to pick that up and keep that going”.

Pouring one of their beers into its chalice glass, Karl admits that it was difficult at the beginning when they took over, particularly when dealing with wholesalers. “They said to us, ‘you’re making a traditional old fashioned beer. It’s not trendy enough’. But we continued with it. We hammered on the same nail”. Resilience.

Part of the desire to continue with tradition was the huge family legacy of the brewery. Their great grandfather, Paul, their grandfather, Leon and their father, Jacques had all produced Flemish red-brown ales. Now it was Karl and Peter’s turn. So how did they feel about working together as brothers?

“I studied economics. It’s logical that I do the commercial and administrative parts. My brother was more technical so we are complementary”. This is the way that the running of the brewery became divided. Peter remains responsible for production and Karl manages the commercial operations. “My brother, Peter, is the brewer,” Karl explains as he sips from his glass. “And I help people to make the right choice.”

DUCHESSE. DUCHESSE. DUCHESSE.

Although the Vichtenaar was their original Flemish red-brown ale, it is the more recent arrival, the Duchesse de Bourgogne, that has become their flagship beer. “We started with the Duchesse de Bourgogne several years ago. This was a more elaborate version of the standard Vichtenaar which we still make. It’s a bit stronger. The Duchesse is 6.2% ABV. and the Vichtenaar is 5.1% ABV. That little bit more alcohol also gives a little more taste to the beer. It’s more refined and better balanced.

She gave a lot of rights to the civilians of the cities here and was very supportive of the commercial activities in those times, including brewing.

Throughout our conversation, Karl refers fondly to the ‘Duchesse’ as if talking about an old friend. This is clearly a lady he has come to know well and with whom he has spent a lot of time. Its vinous aroma and wonderful tartness is balanced by a deep malt sweetness. “Vichtenaar or Echt Kriekenbier can be difficult to pronounce for those who don’t speak Dutch,” says Karl. “Choosing an understandable name is important. Duchesse de Bourgogne is French, but speakers of other languages can understand it”.

The Duchesse of Bourgogne – Mary of Burgundy – was a very important and beloved figure in West Flanders. Having been born in Brussels and later marrying Maximilian I, the Duchesse de Bourgogne seems to be a good choice of name for a rich and well-crafted beer. “She was someone who was very powerful and very important to our region,” says Karl. “She gave a lot of rights to the civilians of the cities here and was very supportive of the commercial activities in those times, including brewing.”

The challenges for the Verhaeghes were far from over. Karl suffered a serious injury in a road traffic accident not so long ago and now requires walking aids to move around. He probably shouldn’t be back in the office so soon but behind his affable character and gentle demeanor is a strong personality as resilient as any of the Verhaeghes who have gone before him.

BARBE FOR VARIETY

On the brewing front, another major difficulty was the brewery’s reliance on one beer. “We were almost a monoproduct brewery,” says Karl. “It was Duchesse, Duchesse, Duchesse. That’s a danger for us. That’s why we started the Barbe range – top fermented beers which we used to make for special events or specific customers but which we now have as a year-round range”.

This new range includes their blond and amber offerings, the Barbe d’Or and the Barbe Rouge, as well as the Barbe Ruby, a strong fruity beer which is a blend of beer matured in oak casks and younger beer to which fruit is added. It has become a commercial version of their more ‘authentic’ Echte Kriekenbier.

The Barbe Noire is what Karl describes as a “Belgian stout”, a dark beer with more sweetness than roastiness and with hints of red fruit, chocolate and peppery bitterness on the finish. “It’s somewhere between a stout and a scotch,” says Karl. “That’s why we call it a ‘scout’. It has some fruity aspects due to the yeast and the choice of different malts. But we don’t want to have the dry aspect that other stouts have as it doesn’t make sense for a smaller brewery to copy a well-known existing beer. We are looking for something authentic”.

Before leaving their company, I ask whether I could take a photograph of the brewery’s front signage. “We don’t have one,” Karl answers with a nervous smile. “We’re not very good at making that sort of fuss”.

His modesty is in keeping with the brewery’s understated influence on the Belgian beer scene. It seems that the Duchesse de Bourgogne does all the talking for them.

*A version of this article on Brouwerij Verhaeghe and the Duchesse de Bourgogne beer was originally published in a previous edition of Belgian Beer and Food magazine*