Belgium’s North Sea coastline, with its segmented lines of beach promenade, high-rise apartments, and polder fields can be navigated on the iconic Kusttram—the longest single tram line in the world. Eoghan Walsh, an Irishman resident in Brussels who is normally unenthralled with the coast, spent three wet days riding the Kusttram to explore its food and drink culture.

Words by Eoghan Walsh

Photography by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Breandán Kearney

Animations by Lucky Dart

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

Stop #56 : Station (Blankenberge)

“Cold and grey and frigid”

The tram hadn’t pulled away from the gaudy lights of the Blankenberge kermis fun fair before the empty seat next to me is filled. On the outskirts of Wenduine, its occupant starts talking to me. Burly, with a thick neck and a beefy hand holding onto a leashed German shepherd, he introduces himself and apologises for his girth. Or at least, that’s what I can pick up from his dense Flemish dialect.

He still has the glow of the kermis and a day at the beach on him, the bright strip lighting of the tram accentuating his neck’s tanned creases. He tells me his name (Daniel), his wife’s (Sylvia), and the dog’s (Wolf). He tells me they are taking the late-night tram back to their holiday apartment just outside of Ostend. He tells me he’s a trucker, a freelance driver midway through a 10-day holiday on the Belgian coast—the first of his professional career.

He finds out I’m Irish—because I tell him—and his sun-weathered face betrays confusion at how he’s ended up talking Flemish to an Irishman on the late tram from Blankenberge to Ostend. So he asks, what am I doing here?

A good question, and one I’d been asking myself throughout a day that’s just leeched the last of its light into the sea on the horizon. I could tell him I don’t really like the Belgian coast, that I might even hate it. That I find it cold and grey and frigid. That I don’t like it in the winter when the north sea winds whip sand into your eyes and cold into your bones. That I don’t like it in the summer either, when all of Belgium descends on an overcrowded 100 kilometre strip of beach and promenade. That its straight lines and dull palette makes me pine for a real coastline, for the earthy greens and browns and yellows of the Irish beaches of my youth.

I could tell him that, to cure this aversion to the Belgian coast, I devised a plan: to ride the Kusttram—the world’s longest tram line—the length of the coast. And, because the best way I know to understand a place is through its food and drink, I’d planned stops off along the way to talk to and taste with the chefs, fishermen, brewers, hoteliers, food historians, and farmers in abundance along this beige-grey thread of North Sea coast. I could also tell my new friend Daniel that this is why I’ve got wet socks, a bruised tomato, and the early premonitions of a cocktail-fuelled hangover.

But he’s on his holidays and doesn’t want to hear this. By the time the tram rumbles into De Haan, conversation has stalled. The luminous tram will take Daniel, Sylvia, and Wolf deeper into the night, down the coast to Bredene and to the rest of their holiday. This part of my journey stops at De Haan station, but my coastal trip continues in the morning.

This time, I’m going to the end of the line.

Stop #36: Koninginnelaan (Oostende)

“Zeezucht”

Er rest ons nog de herinnering

aan rozen, aan Ensor zijn baard

de geur van seringen

het gerucht van de ransuil

de lucht van frambozen

de bloemencorso

een litho van Spilliaert

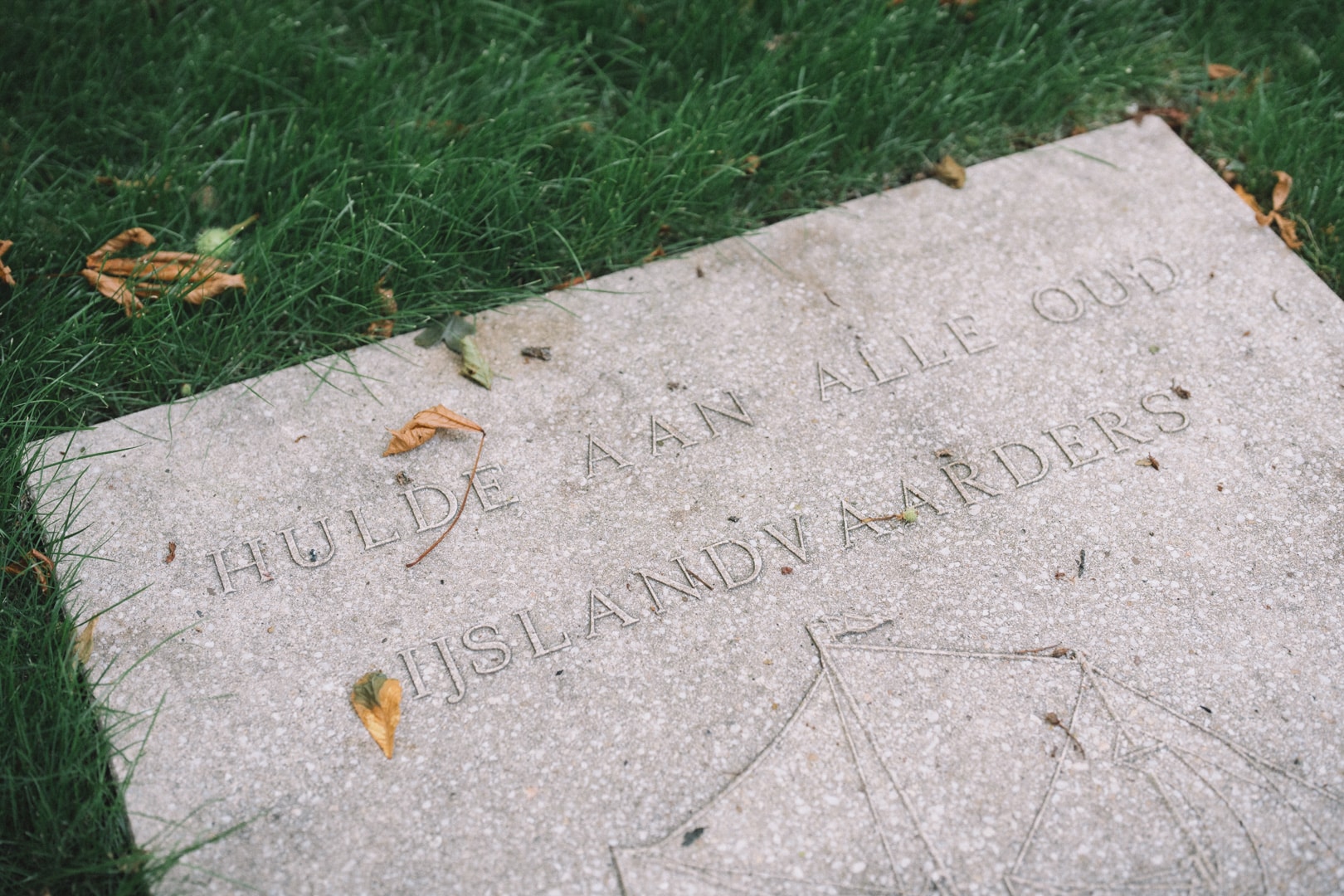

de IJslandvaart

Sehnsucht?

Zeezucht

We still have the memory

of roses, of Ensor’s beard

the scent of lilacs

the rumour of the long-eared owl

the scent of raspberries

the flower parade

a lithograph by Spilliaert

the Iceland voyage

Longing?

Zeezucht

Zeezucht [“sea-sigh”], Hugo Claus

Stop #1: De Panne Adinkerke station

“The longest single tram line in the world”

Belgium has purchase on a roughly 65 kilometre stretch of North Sea coast. Bordered by Bray-Dunes and the French Opal coast to the south and Cadzand and Zeeuws-Vlaanderen in The Netherlands to the north, Belgium’s coast is fully in the province of West Flanders. Along the coast are 15 beach resorts or towns, from major developments like Ostend to smaller towns like De Haan and Koksijde. With a cumulative six Michelin stars in restaurants in the region, the coast has a density of just over 1 Michelin-starred restaurant for every 10 kilometres.

There are breweries too—at least three, depending on your definition and geographical scope (Brouwerij St Idesbald, Jus de Mer, and Stadsbrouwerij Oostende ‘t Koelschip)—and many cafés, restaurants, and bistros with something to offer your non-Michelin guide reader. These businesses and the towns they occupy are all strung out alongside or straddling the metal tracks of Tram 0, the Kusttram, Belgium’s coastal tramline. 67 kilometres long and comprising 68 stops, the tram has been trundling leisurely between these pleasure centres for 137 years.

While it is proud to be the longest single tram line in the world, the Kusttram does not actually stretch end-to-end down the coast. Its southern terminus—which I thought was the first stop but according to the tram’s operator De Lijn is actually the last—is neither on the French border, nor actually within sight of the sea.

Instead, my early morning train from my home in Brussels—skating past wet, flat polder fields with pitched roof village steeples occluded by an early morning mist—terminates in the village of Adinkerke and its well-proportioned brick train station. From here, the sea is a 45 minute walk through corn fields and acorn-strewn dunes, where the entrance to Belgium is marked by a Leonidas chocolate shop housed in a former customs station. By the time the train pulls into the sidings at Adinkerke the mist has congealed into a fine rain. Fortunately, there are already two trams waiting to start their journeys up the coast.

The front of the trams are moulded like Easter Island Moai heads, one of them sharp-angled and the other—a sleeker, newer model—more streamlined. The station abuts the Plopsaland amusement park, out of which leak the screams of children riding roller-coasters branded with their favourite Flemish kids TV characters, and once the tram doors groan open, we pile in. This jangling, humming iron rooster will be my vehicle for traversing the food and drink culture of the Belgian coast. Already the view outside the tram window is distorted by an unrelenting spattering of rain. A sunny day by the seaside this is not.

Stop #8: Sint-Idesbald (Koksijde)

“Terroir”

Iain Wittevrongel, sitting in the dining room of Mondieu, the restaurant he runs with his wife near the seaside town of Sint Idesbald, is keen to talk tomatoes.

Behind the restaurant—housed in a former farm and church complex previously attached to the nearby Ten Duinen abbey—are polytunnels where he grows them alongside fennel, potatoes, and raspberries. Mondieu’s kitchen garden is a labour of love, allowing Wittevrongel to feed his diners the richness of the soil and sandy clay of the nearby dunes and the polder fields.

For a man who likes to get earth under his fingernails, Wittevrongel was born with his feet in the sea. He comes from a family of fishmongers, who still operate out of the same shop, “Mette Julia”, that Grandmother Julia Vyaene-Wittevrongel, herself the daughter of a renowned De Panne fisherman, opened in Sint-Idesbald in 1919.

Iain Wittevrongel grew up surrounded by fish and fishermen, later going to culinary school and working in New York before returning to open, in 2005, his first restaurant on the site now occupied by Mondieu. “I didn’t want to be at the coast,” says Wittevrongel. “[But] near the coast.”

This first restaurant, called Ten Bogaerde after the original name of the complex, won a Michelin star in 2012; a major—if bittersweet—accomplishment: “Customers really expected the unexpected…It [was] a lot of pressure.” It was pressure he decided he could do without, closing it five years later and reopening as Mondieu in 2018 with the mantra, “minimum of fuss, maximum of flavour”. Gone were outré ingredients like yuzu, and in their place a simpler focus on plates of food celebrating the quality of coastal produce.

“Flemish shrimp are the best,” says the old fishmonger’s son, largely because of the generations of local fishermen who know how to catch the shrimp that grow in the warm sandbanks off the coast here so they come ashore in excellent condition. Wittevrongel’s kitchen fuses this maritime tradition with the region’s agricultural hinterland, a melding of soil and sea that he says typifies Belgium’s coastal terroir.

Take a dish like potatoes and shimp. The polder fields around Sint Idesbald grow a lot of the former, and the seas off Koksijde have always been rich with the latter. “If you have potato and shrimps, [some] buttermilk, and [add] a poached egg. Already those four ingredients are [individually] wonderful. Put them together, they’re even more wonderful…That is terroir, for me.”

Fresh North Sea shrimp also means shrimp croquettes. Wittevrongel produces them for drinkers at a small brewery that’s been installed in collaboration with Melle’s Huyghe brewery (of Delirium Tremens fame) in the old pig shed by the complex entrance. The brewery makes a small portion of Huyghe’s Sint Idesbald range of Abbey beers alongside Mondieu-branded house beer. But the brewery is closed this morning, so Wittevrongel suggests another place a couple of stops over. “In Oostduinkerke you have a pub, called the Peerdevisscher.” I mark it in my notebook.

Before I can leave, Wittevrongel ducks into the garden and returns with a pepper-red tomato which he places in my hand. “Coeur de boeuf tomatoes,” he says. “One of the best. If you can, wait for two days. It will be even better then.”

Stop #9: Ster der Zee (Koksijde)

“I have a fish for day and night”

Ik heb een vis voor dag en nacht,

des morgens, als de angst mij wacht,

zwemt hij kalmerend langs mijn voeten,

als ik des nachts de droom opwacht

dan komt mijn vis mij groeten.

I have a fish for day and night,

in the morning, when fear awaits me,

he swims calmly by my feet,

when I wait for the dream at night

then my fish comes to greet me.

J.B. Charles

Stop #13: Bad (Oostduinkerke)

“Sea salt and chlorine and horse shit”

“Passion for horse and sea”. That’s what seduced Johan Casier into becoming a horse-shrimper, or paardenvisser.

Every summer, Oostduinkerke’s paardenvissers organise public demonstrations at the town’s promenade. Casier, a third generation paardenvisser who’s been horseback fishing for 22 years, is usually too busy running the nearby Estaminet de Peerdevisscher café to participate. Looking out the tram window as we bumble into Oostduinkerke, he should consider himself lucky.

Groaning to a halt at the “Bad” tram stop, the wind is sweeping great curtains of rain from the polder fields through the apartment blocks, over us, and out to the beach beyond. Neither hardy paardevissers nor the assembled crowd look put off by this summer storm. The promenade smells of sea salt and chlorine and horse shit. An unspoken signal goes around the gathered paardevissers and they saddle their horses, gather their equipment, and mount up for a short trot to the shoreline where another crowd is waiting for them with umbrellas and brightly-coloured waterproofs like a kind of a mass evangelical baptism.

The horizon and the sea are an indistinguishable grey, disturbed only by silhouettes of the men and women on horseback. They’re sifting for crangon crangon, the common or grey shrimp. People have fished the North Sea’s shrimp-rich shallows for centuries, but it’s only here in Oostduinkerke where the tradition endures.

The most productive catches happen from halfway-September until the first frost, and a typical session takes three hours: from 90 before to 90 minutes after low tide. They use a funnel-shaped net held open by two lateral planks. The horse, the water up to its chest, drags a chain across the sand, creating shock waves that prompt the shrimp to jump into the net.

After 45 minutes in a howling gale, I give up and trudge back through half-moon indents in the sand to the promenade. Wood smoke is in the air and volunteers are setting up a rudimentary wood fired oven to the sound of Pink Floyd. When the paardenvissers return, buckets overflowing, the oven is ready.

It’s methodical and well-choreographed work, the unloading and the sorting of the shrimp. Five men and one woman sit at a sorting table, some chatty, others focusing their taut, muscular faces on sifting the shrimp, removing small flat fish and other detritus. One man stokes the fire with hefty chunks of wood.

The grey shrimp are sloughed into an orange bucket and hosed with fresh water, then tipped into a large makeshift cooking vat with a heavy lid. A fisherman with Gunther etched into his wooden saddle lifts the lid, jostling the shrimp with the cooking liquid and spooning them out of the pan when he’s happy with their shade of flushed pink.

A woman packs these rose garnaaltjes into flimsy cardboard containers, shouting “€1 for a box” to tourists gathered around the makeshift kitchen. They fumble in their soggy pockets for coins and leave with their loot, separating heads from bodies as they escape the wet promenade.

Stop #14 Duinpark (Oostduinkerke)

“You took a horse and you went to sea”

Johan Casier has run the Peerdevisscher café since 2004, when he and his wife took it over from her father—also a paardenvisser. Next door to the Navigo maritime museum, it’s housed in a single storey fisherman’s cottage with a terracotta pitched roof, whitewashed stone walls, and green window shutters.

Inside, the smell of decades of cooked shrimp has soaked into the wooden bartop, the brown-stained wooden tables, and the plastic gingham tablecovers. Pictures of Casier fishing hang on the walls next to childrens’ drawings and old fishing rods. Behind the bar is a large print featuring Oostduinkerke in big bold lettering and a proud image of horse and fisherman wading out to sea.

Casier takes a seat alongside Ian Van Der Stricht, his son-in-law, the café’s chef and apprentice paardenvisser. “It’s tough,” Casier says of a proper day’s horseback fishing, which might explain why, alongside the devastating impact of industrialisation, only six paardenvissers remained when Casier began fishing with his father-in-law in the early 2000s. But this ancient tradition is experiencing a startling revival, and once Van Der Stricht completes his training, that number will have more than doubled.

The turning point came in December 2013 when UNESCO added paardenvissen to its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Speaking to local media after UNESCO’s announcement Eddy D’Hulster, founder of the organisation “d’Oostduinkerkse paardenvissers”, said: “A true horse fisherman loves the sea, what the sea produces, and his horse, in the depths of his heart.”

A true paardenvisser also now has to undergo an official accreditation, a stipulation of the UNESCO recognition. “[Before], you’d take a horse and go to sea,” Casier says. “Did it work out after a couple of attempts? If yes, then you were included in the group.” For Van Der Stricht, the process is different, involving a two-year apprenticeship, a theory exam, and a practical skills test.

Van Der Stricht, who says he “washed up here from inland”, never expected to become a paardenvisser, but like Casier before him, knows that it was inevitable once you married into a paardenvisser family: “I always found it fascinating, but it wasn’t like everyone was telling me, ‘You have to do it later’.” But when the café closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic and Van Der Stricht was confronted with unexpected time off, he started joining Casier on fishing sessions. Soon they were talking about buying him a horse, and by 2024 he should have completed his apprenticeship.

Mentoring Van Der Stricht is also an excuse for Johan Casier to get back in the saddle: “I do miss it. [But] we are going to make an effort this year. We have to either way, with this one’s education,” Casier says, nudging Van Der Stricht.

Retirement is not on the cards. “You fall into it, don’t you?,” Casier says. “You meet the love of your life and it turns out her father is a paardenvisser. It grabs you by the neck. Once you’ve been in the sea, that’s it, you’re on your way.”

Stop #25: Belle Vue (Westende)

“Le Plat Pays”

Avec la Mer du Nord pour dernier terrain vague

Et des vagues de dunes pour arrêter les vagues

Et de vagues rochers que les marées dépassent

Et qui ont à jamais le cœur à marée basse

Avec infiniment de brumes à venir

Avec le vent de l’Est, écoutez-le tenir

Le Plat Pays qui est le mien

With the North Sea as the last wasteland

And waves of dunes to stop the waves

And vague rocks that the tides exceed

And who forever have their hearts at low tide

With endless mists to come

With the east wind, listen to it hold

The Flat Country that is mine

“Le Plat Pays”, Jacques Brel

Stop #26: Krokodiel (Middelkerke)

“We were born in the bed of salt and will perish in the brine.”

On a good day, you can see 25 kilometres to Diksmuide from the top of the Drakentoren (Dragon’s Tower). Today is not a good day. The storm has relented but the swollen clouds remain and Middelkerke, a kilometre to the east, is barely visible. The rain has burrowed under my fingernails, and the slate grey sky and concrete sea have formed an enveloping dome over the landscape.

The coast here is an orderly, narrow strip of land segmented into parallel sea-beach-promenade-apartments-highway-tram-field lines. It’s often easy, at ground level, to forget the beach is there at all, with the monotonous rows of 1960s mushroom-coloured apartment towers with names like Helix Zeezicht and Residentie Hawaii shielding land from sea.

This Belgian coast is hard to love and easy to scorn. It lacks the rugged profundity of Scandinavian fjords or the fractal chaos of Ireland’s Atlantic coast. Its colour palette is grey-beige and its soundtrack is less Charles Trenet’s La Mer and more Brel’s plat pays.

In this weather, it’s a melancholy, haunted coastline. Belgium’s first queen came here to die, in a small house off the Ostend promenade. Her son Leopold II ushered in a belle epoque golden age built with Congolese blood money. Before Leopold, and before the arrival of train lines to Ostend, Belgium’s coast was made up of small fishing and farming communities. The farmers tilled the inland polders. From the 17th century, fishermen—and it was always men—sailed the Ijslandvaart, a six-month-long expedition to Icelandic fishing grounds in search of cod, gutting, salting and storing it until they made land at Nieuwpoort, or Ostend, or Duinkerke. Such was the sea’s pull, 26% of the population of Oostduinkerke in 1900 were fishermen.

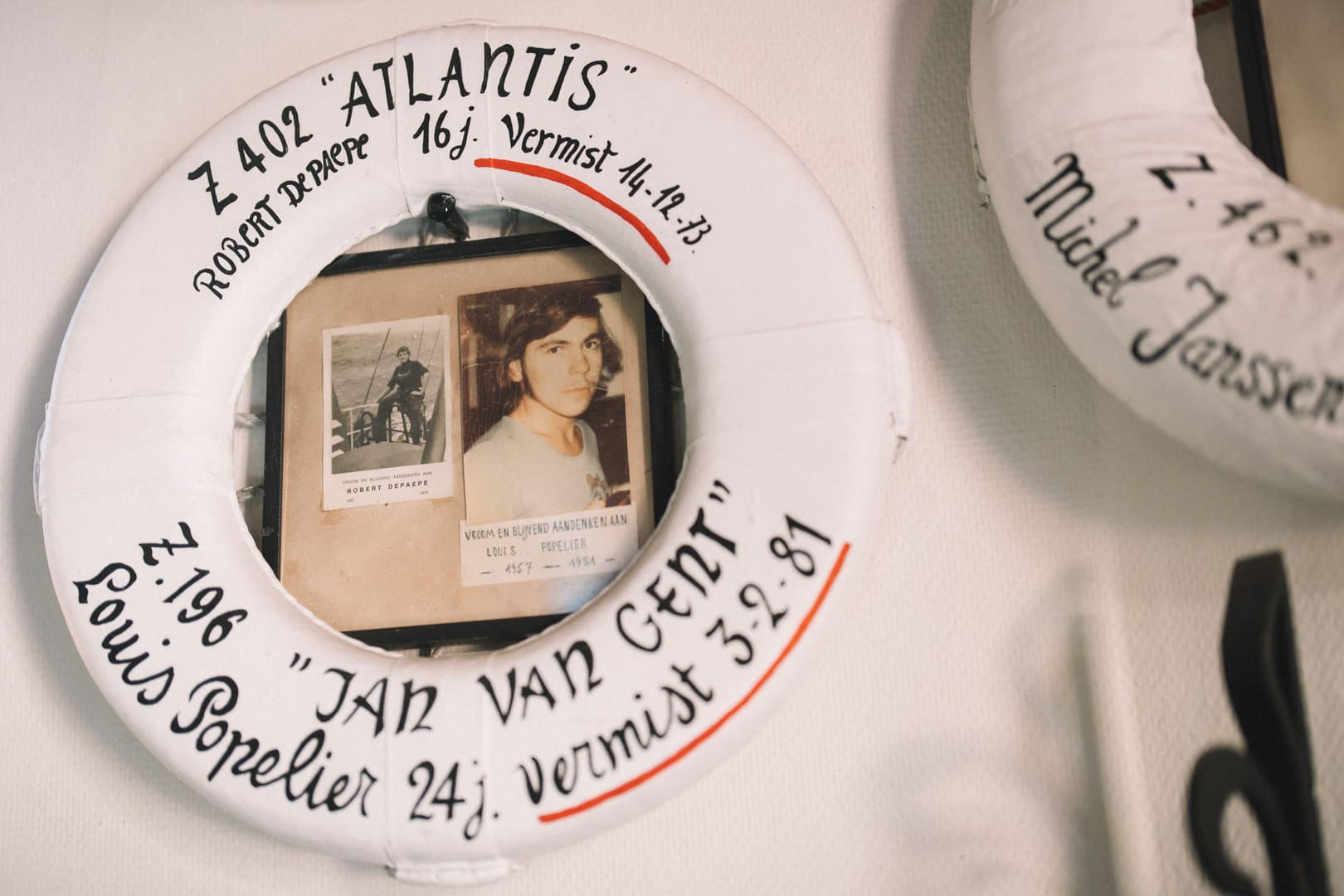

It was an unforgiving journey, one which was doomed by the advent of steam trawling, the arrival of modern tourism, and the intermittent outbreak of cod wars with Iceland. The final Ijslandvaart departed in 1995 and beside the Estaminet de Peerdevisscher is a small chapel and granite monolith inscribed with the names of 489 men, the dates of their disappearance at sea, and their home ports. On its base is an epitaph that reads: “we were born in the bed of salt and will perish in the brine”.

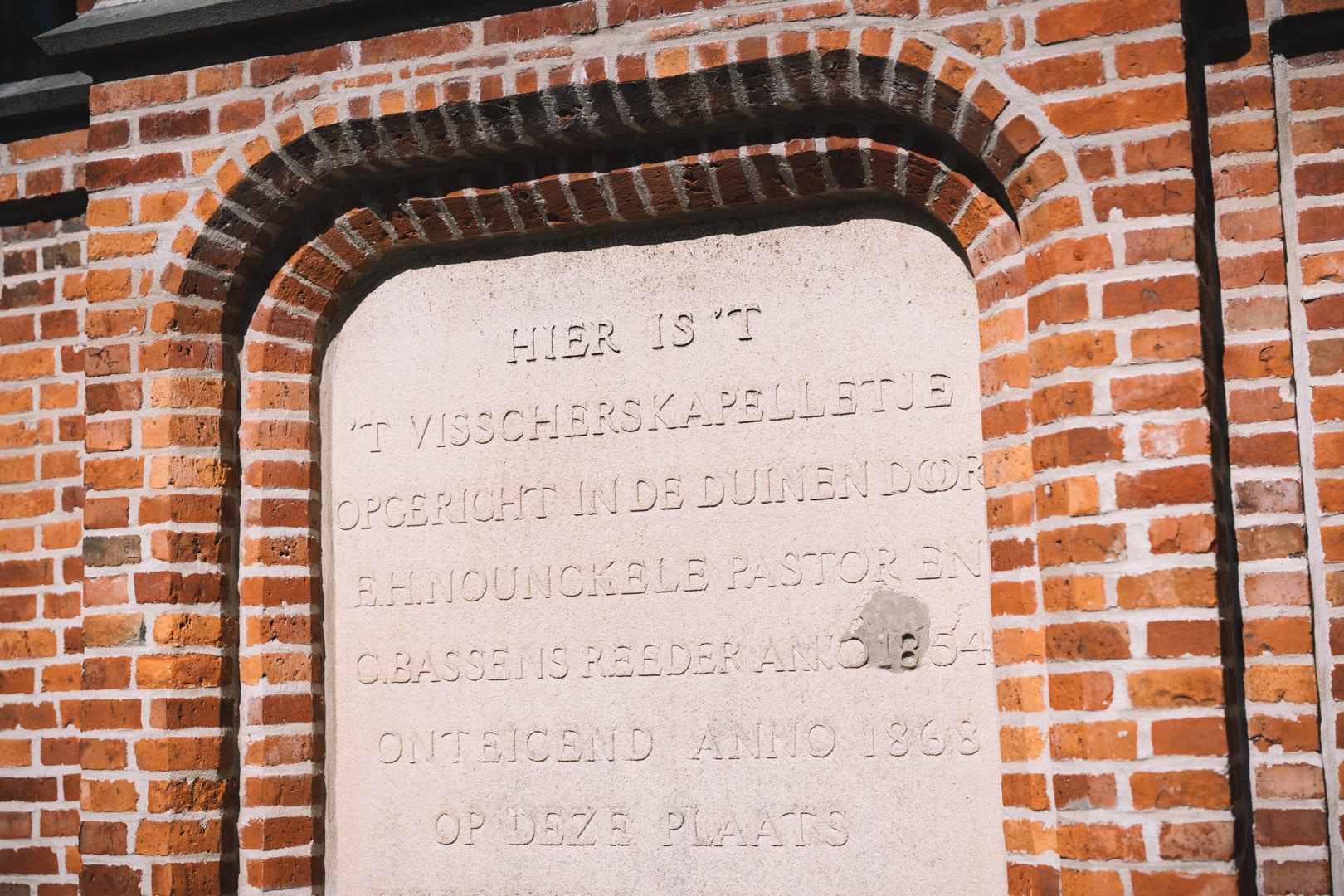

Up the coast in Heist-aan-Zee is a little redbrick, one-room visserskapel (fisher’s chapel) smelling of candlewax and incense, with maritime-themed stained glass windows. The walls are crowded with white rescue buoys, each one representing a fisherman or crew lost at sea and decorated with photographs—some black and white, others sepia-toned—of men who never returned home.

But the coast didn’t just lose its men to the sea. It also lost them to war.

The trenches of World War I bisected the coast, and its victims are memorialised with white headstones in municipal cemeteries, in abandoned military installations, and in the gargantuan Albert I memorial looming over Nieuwpoort’s harbour. It’s no wonder, perhaps, that this maudlin coast has attracted lost souls seeking refuge from personal trauma in the windy dunes around Ostend.

Stop #34: Northlaan (Oostende)

“Oostende Bonsoir”

Il est trop tard

Comme tous les soirs

J’suis seul avec toi

Oostende, bonsoir

Tu me promènes, Oostende

Comme tous les soirs

De bière en bière

Et d’histoire en histoire

It’s too late

Like every night

I’m alone with you

Ostend, bonsoir

You take me for a walk, Oostende

Like every night

From beer to beer

And from story to story

“Oostende Bonsoir”, Arno

Stop #37: Marie Joseplein (Oostende)

“There are places that I’d rather be. But I probably need to be here.”

The weather has improved, but not my mood. I’m supposed to meet Els Snick—literary translator, University of Ghent professor, and Chair of the Flemish-Dutch Joseph Roth Society— at Ostend’s Brasserie du Parc, on the Marie Joséplein. But we had to reschedule and I’m left enjoying my soup of the day and pintje alone.

Brasserie du Parc opened in 1926, and some Art Deco embellishments—chrome fittings, stained glass, wooden banquettes, and seagreen marble worktops—have survived. A century of refreshed drinkers have worn deep grooves in the stairway’s marble treads, and the big windows trill with the rumble of passing trams. I’d arranged to meet Snick to talk about two of the Parc’s famous clients: Austrian-Jewish writers Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig.

Zweig, remembering a youthful visit to Ostend, convinced Roth, who hated the sea, to spend a month with him there in July 1936. Over coffee in the Parc and Verveine in their favourite Italian, the men talked. Both were persona non grata in Nazi Germany. Roth was escaping debts, collapsing health, and a failed marriage. Zweig was having an affair with his secretary. But the Ostend they arrived in was not the one of Zweig’s youth. “It was no longer the big city of the Belle Epoque, of the Belgian kings,” Snick says. Leopold II’s successors had discontinued his lavish spending that transformed Ostend into the koningin der badsteden—“queen of beach resorts”, and its rougher edges were returning.

It didn’t matter much. Their Ostend sojourn was only a brief interlude between personal and global calamity. “Roth is committing slow suicide, he knows he’s dying,” Snick says. “1936 is the breaking point for them. They know it’s finished for their country, for their heimat, for the Jews in Europe.” By 1939 Roth was dead in a Paris hotel room and three years later Zweig overdosed on barbiturates in his Brazilian villa.

Unlike them, and most of Ostend, Brasserie du Parc survived the war intact. “But that’s all,” Snick says. Into the post-war reconstruction arrived Belgian writer Hugo Claus, who’d rent a hotel garret and spend his nights playing cards and drinking with Ijslandvaart fishermen with “ears and eyelashes full of salt.” Claus self-diagnosed himself with zeezucht, a yearning for the sea, and his last wish was for his ashes to be scattered on Ostend’s beach.

American singer Marvin Gaye washed ashore in Ostend in 1981, a reluctant visitor that winter who played darts in smoky bars with bemused locals and wrote the last big hit of his career, “Sexual Healing”.

Gaye, in a documentary recorded in that lost winter, says of Ostend: “There are places that I would rather be. But I probably need to be here.”

Claus and Gaye revelled in Ostend’s maritime roughness. “Ostend had a very bad reputation,” Snick says. “Boats came from England, with passengers that came to drink, and drink, and drink. And there were many fights in the cafés.”

The fights have stopped. As has the Dover ferry. But down alleyways off the promenade, Ostend still hums with energy.

Stop #38: Station (Ostend)

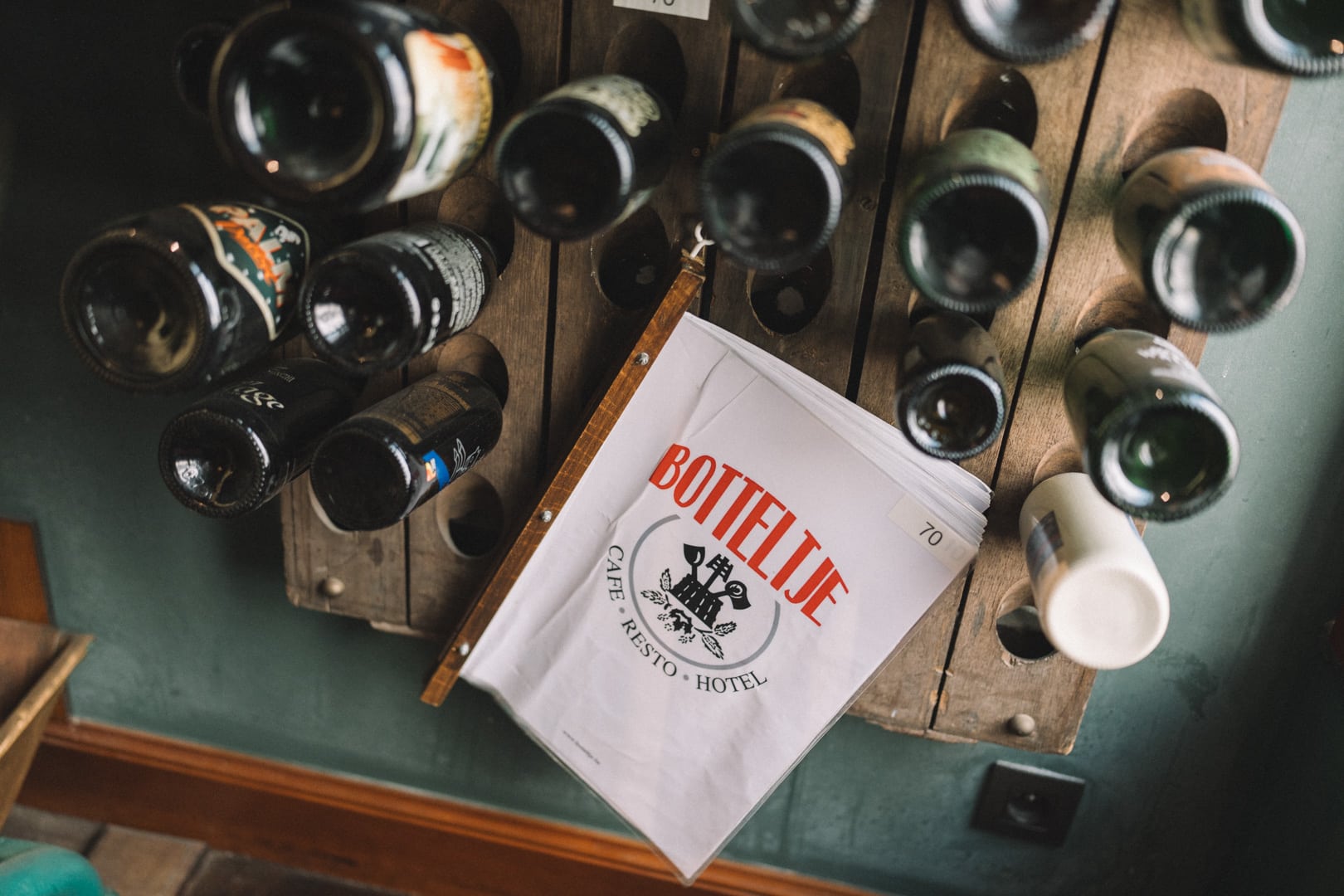

“The Small Bottle”

The Ostend that Jean-Pierre and Henriette Desimpelaere arrived into with their son James in tow in 1983 was one where the ferries still ran and the tourists still drank. They’d come from Turnhout to run a small hotel near the beach.

“We had 20 rooms…[and] one bath in the whole building, and the toilet was in the hallway,” says the younger Desimpelaere, with the average price of a night’s stay somewhere around €10. “There was just a small bar…[where] only about 30 people that could sit.” On their very first weekend running the Hotel Marion, it was overrun with revellers enjoying a local beer festival.

Forty years on, James Desimpelaere is in charge, and the hotel has been renamed (Het Botteltje, “the small bottle”), expanded, and modernised. Beer is everywhere at Het Botteltje. The bar has the booths, brass fittings, and polished brewery-branded mirrors of an old-style pub. The walls are covered in memorabilia from breweries past and present. There’s even a fingerpost near the entrance marked with the distances to famous breweries. It smells like a pub—unemptied slop trays, degreaser, and disinfectant—and those English tourists that came in the 1980s would easily recognise it as a pub.

Together with his father Jean-Pierre, James Desimpelaere has grown the beer list for the hotel’s now-extended bar to include somewhere between 280 and 310 entries. It’s a thick folder featuring explanatory texts about different beer styles and a compendium of beer-themed jokes. While I pore over it, Jean-Pierre sidles over to my booth and tells me I should take a look at the ancient heat exchanger they have installed on the bar’s first floor.

What sets Het Botteltje apart from Ostend’s other beer-centric cafés is Desimpelaere’s merging of his passion for beer with his training as a chef. “People would say, ‘What are they doing, they’re cooking with beer?!’”, he says of early reactions to dishes he was making where he experimented with beer as a key ingredient. Undeterred, he continued pairing and incorporating beers into the bar’s food menu—in bread, in their vispannetje, and in their Rochefort 10 ice cream. He also uses beer-infused shrimp croquettes, serving them alongside more orthodox croquettes made according to the rules of the Oostendse Garnaalkroketten erkende streekproduct (“recognised regional product”); rules which require them to be made with at least 40% shrimp that’s been caught and sold by local fishermen.

Getting Ostend’s particular kind of shrimp croquettes official recognition is part of a plan by Ostend’s local government to use its culinary scene to lure more tourists to the coast. Gone are the €10 rooms. People want, Desimpelaere says, “a good meal, a good sleep, [and] a good drink.” For the food, the city has worked with chefs like Desimpelaere to get Ostend croquettes onto menus across town. When the tourist board wanted a local beer to pair with them, they tapped up the only brewery in town: Stadsbrouwerij ‘t Koelschip Oostende.

Stop #39: Weg Naar Vismijn (Oostende)

“Krevet”

From ‘t Koelschip’s shaded terrace a short walk from Het Botteltje, you can see the offices of Tourisme Oostende, a squat concrete and glass building plastered with a large blue banner advertising “Oostende — de stad aan zee”.

“They were following our progress,” says Ive Mostrey of the office’s employees, who knocked on Mostrey’s door one day with an intriguing proposition. Together with Sandy Major, Mostrey runs Stadsbrouwerij ‘t Koelschip from the beer shop the pair founded in 2010. Mostrey is the salesman from a family of Izegem victuallers. Major’s family used to run an Ostend fish restaurant and she’s now ‘t Koelschip’s autodidactic brewer.

The pair started out in beer wholesale before opening their shop and eventually starting to brew in 2014 on a tiny 60 litre kit. “We wanted to make good, honest beer,” Major says over the sound of honking late-afternoon traffic. “We want to eat well, we want to drink well, and we want to enjoy the small things in life.” Which, for them, meant dry, sessionable beers like their Saison a L’Ostendaise, a Belgian Saison brewed with seasalt. “No IPAs,” affirms Ive. “We didn’t want to get into the hype.”

By the time the tourism office called about a possible collaboration, Major had graduated to a more substantial second-hand 500-litre brewhouse. Their pitch was simple: in autumn 2020 Ostend announced Kobe Desramaults, a Michelin starred chef and television personality, as its first “culinary curator”. A part of his brief involved working with local producers and promoting the characteristic flavours of Ostend: the croquette; and a beer to go with it. Could Kobe Desramaults, the tourist people asked, drop by ‘t Koelschip for a chat?

Agreeing with Desramaults on what kind of beer they wanted was easy. “[Something] light in alcohol, with a very fresh taste, a little bit of citrus, maybe a little sourness,” Major says. hey’d been told by restaurants selling their beer that their Saison went well with fish. Major got to work on tweaking the recipe.

Desramaults escaped into the dunes to forage for herbs to give the beer a flavour of the coast, returning with bouquets of Chamomile and other assorted edible plants, smoking them and making tea-like infusions to get the dosing right. One final taste of Ostend was the brewery’s house yeast, a strain Mostrey claims has a unique character thanks to their years of fermenting with open vessels in the sea air. “We have a ‘contamination’,” he says. “But a positive one.”

In October 2020 they released Krevet, a beer that took as its starting point the Saison style and took it in a slightly different direction, featuring a drawing of an Ijslandvaarder trawler in rough seas. The beer, when it finally made its COVID-delayed appearance on menus across Ostend, was something of a hometown lap of honour for Major. “It felt like we proved that we could do it, because if they [the tourist office] put their name on something we made, it speaks for both of us that it’s good and [it’s] quality,” she says. “It was finally a collaboration with my city.”

Stop #40: Duin en Zee (Oostende)

“The Real People”

Sandy Major’s city was once a fishing village, before it was a royal resort. Then it became a refugee waystation. Later it was a bawdy port town.

Today there is a new Ostend rising on the bones of the old fishing industry to the east of the city’s train station. Under a bloodshot sky, my tram loops around the harbour under the shadows of gleaming, computer-generated apartment blocks in tasteful white and gold cladding, some finished and others existing only on the glossy hoardings. It is not yet clear what kind of people are going to populate the city’s latest new iteration, and whether it will leave room for its predecessors.

“They are people with money,” James Desimpelaere of Het Botteltje says. “If half of the apartments are second homes and everyone visits at the same moment, then great [but]… what if nobody lives there for the rest of the year?”

Professor Els Snick shares his fears. “[With] gentrification…maybe now Ostend will change,” she says. “But…the real people are real people from Ostend. They’re poor fishermen. Ijslandvaarders. Old folk singers. Rough people who like [a drink].” To illustrate her point, Snick namechecks the singer Arno, born in Ostend, described by one reviewer as halfway between a playboy and a tramp, and famous for his recognisable gravelly voice and his rowdy songs. Songs like Oostende Bonsoir, a heartfelt ode to his hometown and after which ‘t Koelschip named a beer. “He’s so typical Ostend,” she says.

Stop #65: Willemspark (Knokke)

“Knokke oh Knokke”

Knokke, oh Knokke ik laat mij graag lokke

Want jij blijft voor mij nummer 1

Zo een ambiance, zo een elegance

Vind je in Knokke alleen

Je strand en zee zijn werkelijk magnefique

Je vogels in het Zwin die zijn uniek

Knokke, oh Knokke I like to be lured

‘Cause you’re number 1 for me

Such an ambiance, such an elegance

You can only find in Knokke

Your beach and sea are really magnificent

Your birds in the Zwin are unique

Eddy Wally – Knokke oh Knokke

Stop #66: Duinbergen Duinbergen (Knokke)

“Melting Pot”

Knokke is many things.

Knokke is the end of the line, the last tramstop before Holland. Knokke is where King Albert II holidayed with his mistress and their daughter. Knokke is the most expensive place to buy property in Belgium. Knokke is the one coastal town you’re more likely to hear French than Dutch.

Knokke is the second home of millionaires and former prime ministers. Knokke is where the coast’s rectilinear march of apartment blocks peters out into expensive villas and the protected Zwin wilderness where sea, sand, and polder elide.

Knokke is also home to cocktail bar The Pharmacy. At the time of my visit, it was located in a former antiques shop between the beach and the Duinbergen Duinbergen stop where I’m meeting my next interviewee, Jeroen Van Vaerenbergh, but since our chat, the bar has moved to a new and very trendy home on Knokke’s Lippenslaan. Van Vaerenbergh calls himself De Foodarcheoloog (“The Food Archeologist”), and he works to revive historical food traditions—as he says, putting “mediaeval times on your plate”.

His Verdwenen Zwinhavens (“Vanished Zwinports”) project is a collaboration with Knokke’s tourism agency, reviving a medieval terroir that emerged in the Zwin marshlands east of Knokke around a network of harbours stretching from Bruges to the sea. In the 12th and 13th centuries these Zwinhavens were, Van Vaerenbergh says, “a melting pot, literally, of all different cultures and tastes…[that] combined with the local terroir of the polders.”

They trafficked in pomegranates from Spain, cinnamon from the east, and cod from Scandinavia, creating a terroir built on soil, sea, and sailboat. The polders were good for cattle and grain. The sea supplied shrimp, mackerel, and Norwegian stockfish, producing a staple diet, Van Vaerenbergh says, of “bread and fish and beer.”

The Zwinhavens project is Van Vaerenbergh’s attempt to recreate this blend of the exotic and the ordinary. He enlisted 20 local food producers—farmers, bakers, chocolatiers—and gave them a mediaeval larder featuring Damascan rose water, saffron, and figs.

Some made jams with grains of paradise, others chocolates infused with hops. The Pharmacy’s Noa Van Ongevalle fashioned a cocktail with vodka, leftover bread—and mackerel. “It’s very subtle…sort of smoked, fishy, oily,” Van Vaerenbergh says. “It doesn’t taste how it sounds!”

Van Vaerenbergh wants the project to reconnect Knokke with its history alongside showcasing the creativity of local producers. He also wants tourists to experience the coast in a new way. “We have such a small coastline, one that’s built all the way along, you [almost] have to be with your feet into the water to have a connection with the sea,” he says. “But that the sea has something to do with food and that it was part of the way of life here, that’s something this project tries to show…[as something] you can taste in a cocktail.”

Only I can’t, because they’ve run out. We make do with two pineapple cocktails, and then two more. Jolly, and wobbly, we follow the tram lines past overstuffed villas back to our stop, riding together until Van Vaerenbergh disembarks near Blankenberge. His seat is taken at the next stop by a burly man with a large dog.

Stop #67: Station (Knokke)

“Seeping in”

The next morning I have dried out and so has the coast; the sky is clear, the sun hot, and the tram full of sweaty bodies and sandy buckets. There is only one stop left on my itinerary: Knokke Station is the end of the line but its Bentleys with French licence plates and bourgeois art galleries are boring. On a tip from Van Vaerenbergh, I’ve rented a bike to explore the Zwin.

At the town’s edge, rolling dunes insterspersed with white-stucco villas replace the rows of apartment blocks and soon I’m left cycling on raised earthen banks above sun-charred yellow fields. Yesterday’s rain has evaporated in the morning sun, and it’s nullified any lingering effects of last night’s cocktails.

The bike path swings inland, but the wind still carries a salty tang and the field birds are drowned out by marauding gulls. The Zwin is flat and quiet and green, its lazy merging of land and sea not a side of the Belgian coast I’d seen before. I started to think that of everything I’d seen on my journey, this reminded me most of the Irish seaside of my youth—the feeling that the sea is close, just over the next rise, even if you can’t see it.

Sweaty after my cycle, I arrive at one of Van Vaerenbergh’s collaborators—the Hazegras farm, where owner Lieve Gunst has made a lemon sorbet infused with gingery grains of paradise. Devouring my ice-cream in the shade, I was reminded of something Van Vaerenbergh said: “Just by tasting one ingredient [people] can start to think” differently about a place. “When you taste something and…you connect with it, with your senses, it stays a lot longer in your memory.”

My first sense memories of Belgium’s coast were black and white. But after two days trundling leisurely from De Panne to Knokke, colour was seeping in.

Iain Wittevrongel’s bright red tomato. A fisherman’s yellow rainmac and the pink of freshly-boiled shrimp. The scuffed mauve of tram seats and the fizzy gold of ‘t Koelschip’s Saison. And this morning, the glorious technicolour blues and greens of the Zwin, the electric yellow of my icy sorbet. The rumble and squeak of the tram and the lowing of nearby cattle have replaced my old coastal soundtrack of bracing seawind and squawking gulls.

The Belgian coast was never going to be able to replicate my feet-in-the-sand, teeth-clenchingly-cold, choc-ice-after-swimming memories of childhood Irish beaches. My first experiences of it convinced me that its drab corners couldn’t satisfy my own yearning for the sea.

But on the ride back into Knokke, I began to wonder whether I’d finally been presented with a version of the coast that could satisfy my yearning for the sea in the same way that Hugo Claus salved his own zeezucht with memories of Ensor and raspberries, lilacs and the Ijslandvaart.

Arriving home in Brussels that evening, I turned to my wife and said, sheepishly, almost confused: “I think I might like the Belgian coast.”

*