The Flemish town of Geraardsbergen is famous for its association with a small cake called the mattentaart. The cake has a long history, is a source of unifying pride, and dominates signs, shops, and conversation in the town. However, it turns out that the Geraardsbergse Mattentaart is in a precarious situation.

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Food Group” series. Read more.

I: “M Town”

Geraardsbergen is known as the town of three “M”s: the Manneken Pis; the Muur; and the Mattentaart.

I park my car on the Geraardsbergen market square, beside the first “M”, the Manneken Pis, a small statue of a naked little boy urinating into a fountain. It outdates the Brussels version by a couple of centuries, but receives only a fraction of visitors, perpetually overlooked.

From the market square, I make my way to the top of the second “M”, the “Muur”, a steep, narrow cobblestone road which reaches its summit at the Oudenberg hill. At the top I see picturesque views of cute buildings with hilly streets, winding in and out through the green landscape of the Flemish Ardennes and the Dender Valley. For decades, the Muur was the most iconic climb of Belgian cycling. But it was cut from the Tour of Flanders because Geraardsbergen refused to pay race organisers to include it in the Tour.

I watch cyclists zoom past me on their way up the hill. When they get to the top, they all do the same thing. They stop, get off their bikes, and out of their bags they each produce a cake that looks like a pie. It’s the third “M”: the Mattentaart.

The Mattentaart—translating into French as Tarte au Maton—is a small cake of around 8 cm in diameter made from a filling of curdled milk (the matten) mixed with eggs and sugar, and encased in a golden yellow puff pastry exterior.

The texture on the inside is described by Geraardsbergenaars as “nis” (somewhere between wet and dry) in contrast to its crunchy crust. The little raised central tip of the mattentaart is known as its “roosje” or “little rose”. I’ve come to Geraardsbergen to find out how such a simple little cake became so important to the people that live here.

Arne De Winde has agreed to guide me through the streets of Geraardsbergen, a municipality which includes the town of Geraardsbergen itself as well as fifteen other villages. De Winde—a self-described “mattentaart freak” and a proud Geraardsbergenaar—works at two universities in Belgium: as a lecturer and researcher at the LUCA School of Arts in Ghent, and as a professor in Architecture and Art at the University of Hasselt. He’s tall and wiry, with a nervous energy and an intellectual disposition, and he’s brimming with enthusiasm.

Like all Belgian towns, there are lots of bakeries in Geraardsbergen. As we pass them, De Winde points out that each has a different word displayed in their front window. It was part of a project born from constant questions from visitors about which bakery had the best mattentaart. Now, visitors can get a map of twenty-four bakeries in the area with each having chosen the one word they believe best describes their mattentaart: the wet one; the creamy one; the shiny one. For the bakeries, it was a display of unity through their points of difference, and it equipped visitors with digestible information to make their own subjective choices.

As he guides me around, De Winde is honest about the challenges faced by the town.

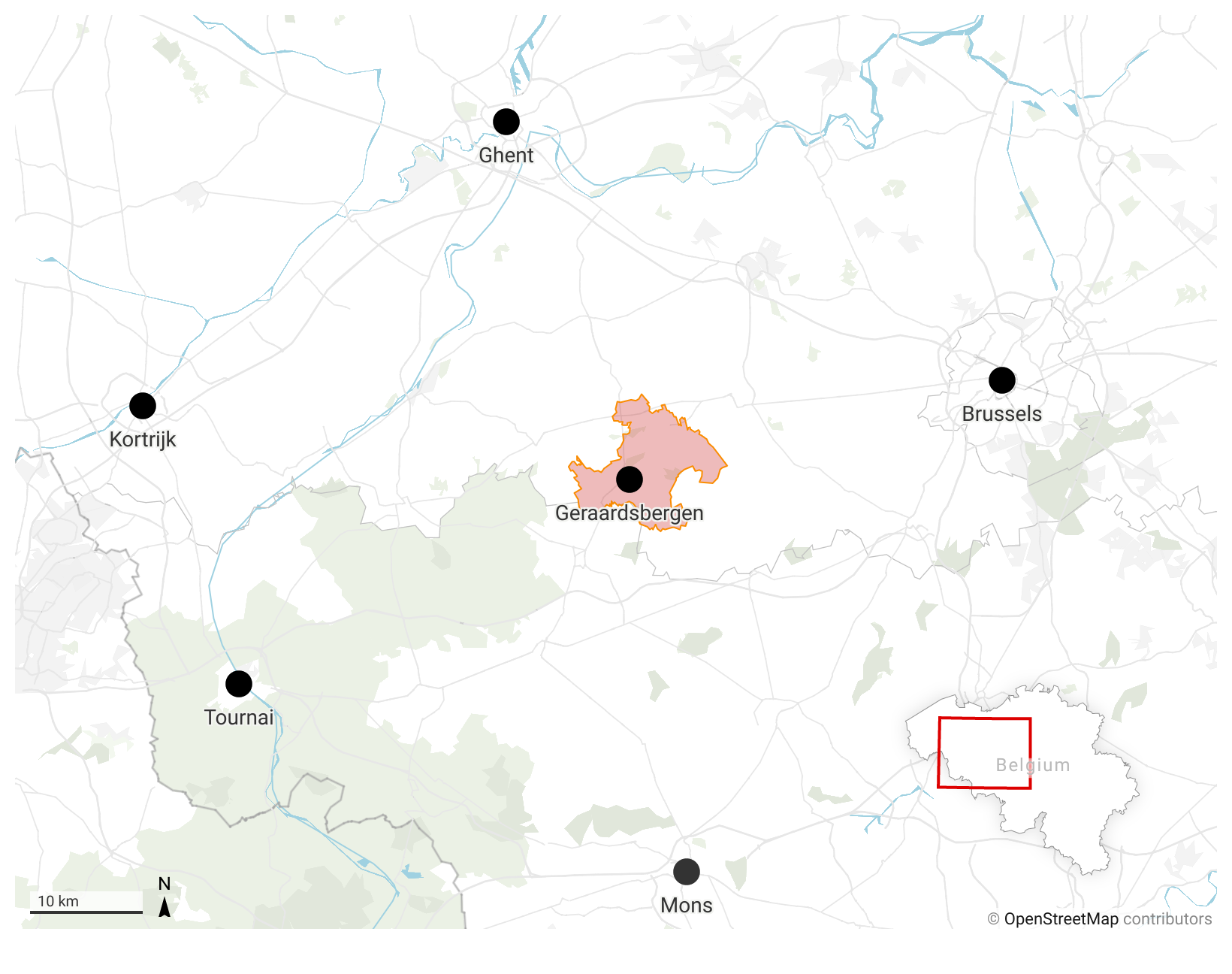

Huge trucks parked in the town’s narrow central streets have suffocated mobility. Much of the charming architecture is dilapidated. No arts centre. Statistics relating to child poverty, speeding incidence, and alcoholism are among the highest in Flanders. There’s a monument of an elephant in the town accused of glorifying a colonial past, and a lack of diversity on the lists of the various political parties. Even though it is close to a major highway, and easily reachable by train from Ghent and Brussels, Geraardsbergen feels geographically separated; a border town on the Flemish-Walloon language divide located in what De Winde describes as the “marginale driehoek”: the “marginal triangle” of Ninove, Aalst and Geraardsbergen.

De Winde sometimes jokes that “M Town” stands for “Marginal Town”.

Geraardsbergen’s Muur and Manneken Pis are former glories, in a way lost to other towns and cities in Belgium. The third “M”—the Mattentaart—remains Geraardsbergen’s best chance for cultural significance. The cake dominates signs, shops, and conversation here. It’s a source of unifying pride in the town. But it turns out that the Geraardsbergse Mattentaart is in a precarious situation. The cake’s historic link to “M Town” is under serious threat.

II: The Baker

Johan De Froy bakes me my first mattentaart and it is glorious.

De Froy originally studied to be an accountant, but after a spate of bad exam results, his parents landed him a holiday job at a bakery to show him what it was like to work with his hands. He was immediately hooked. “You make a cake for a birthday and when you see a child of six years old and he’s happy, that was for me,” says De Froy. He worked for ten years for other bakers in Geraardsbergen before opening Bakkerij De Vesten as his own business twenty-one years ago.

To make his mattentaart, De Froy buys matten directly from local farmers. The matten is a curd which has been produced by farmers applying heat to raw cow’s milk and adding either buttermilk or vinegar to prompt a coagulation. De Froy adds sugar to the matten, gently stirring, and then egg yolks, gently stirring again, and then egg whites which have been whipped up, gently stirring for a final time. This produces a sweet, moist, crumbly filling, which is then wrapped in fine layers of puff pastry before being baked in an oven.

De Froy has two ovens: one for his bread, which is heated by bars filled with liquid oil; and one for his mattentaart, which is heated with air to give more volume to the cakes. The mattentaart he presents to me is sweet and moist on the inside, with an eggy, cheesecake-esque flavour; and crunchy and flaky on the outside. Much of the puff pastry melts in my mouth, but some disintegrates over my shirt and trousers.

I’ve just had the “natuur”; the pure mattentaarten made with only matten, eggs, sugar, and pastry. De Froy himself sells a larger version with jam spread across its base. He also bakes one with almond extract. These variations are considered by many to be sacrilege, flirting dangerously into the territories of Frangipane (butter and flour rather than matten) or Tourteau Fromagé (curdled goat’s milk with a dash of cognac). Other versions of the mattentaart are violently rejected by Geraardsbergenaars: mattentaarten made with pears or krieken; mattentaarten made with cream; and even mattentaarten made with chocolate. In the eyes of De Froy, the natuur is the one true mattentaart: “Matten, eggs, and sugar,” he says. “Nothing more. Nothing less.”

Johan De Froy is what locals call a “warme bakker” (a “warm baker”), one who prepares and bakes everything himself. There are also “koude bakkers” (“cold bakers”) who buy pre-prepared and pre-baked cakes and sell them in their own shops. Olav Geerts was a koude bakker for years, a well known figure in his early seventies with a long wispy beard and a penchant for wearing interesting hats. Between 1984 and 2016 he sold mattentaarten from “Olav’s Mattentaartenhuis” on the Brugstraat in Geraardsbergen town centre. A feud with the owner of a mattentaart shop across the street (The Chicken Palace) reached such a level of national intrigue that the Belgian monthly magazine Plus ran a story about “The Mattentaarten Wars”.

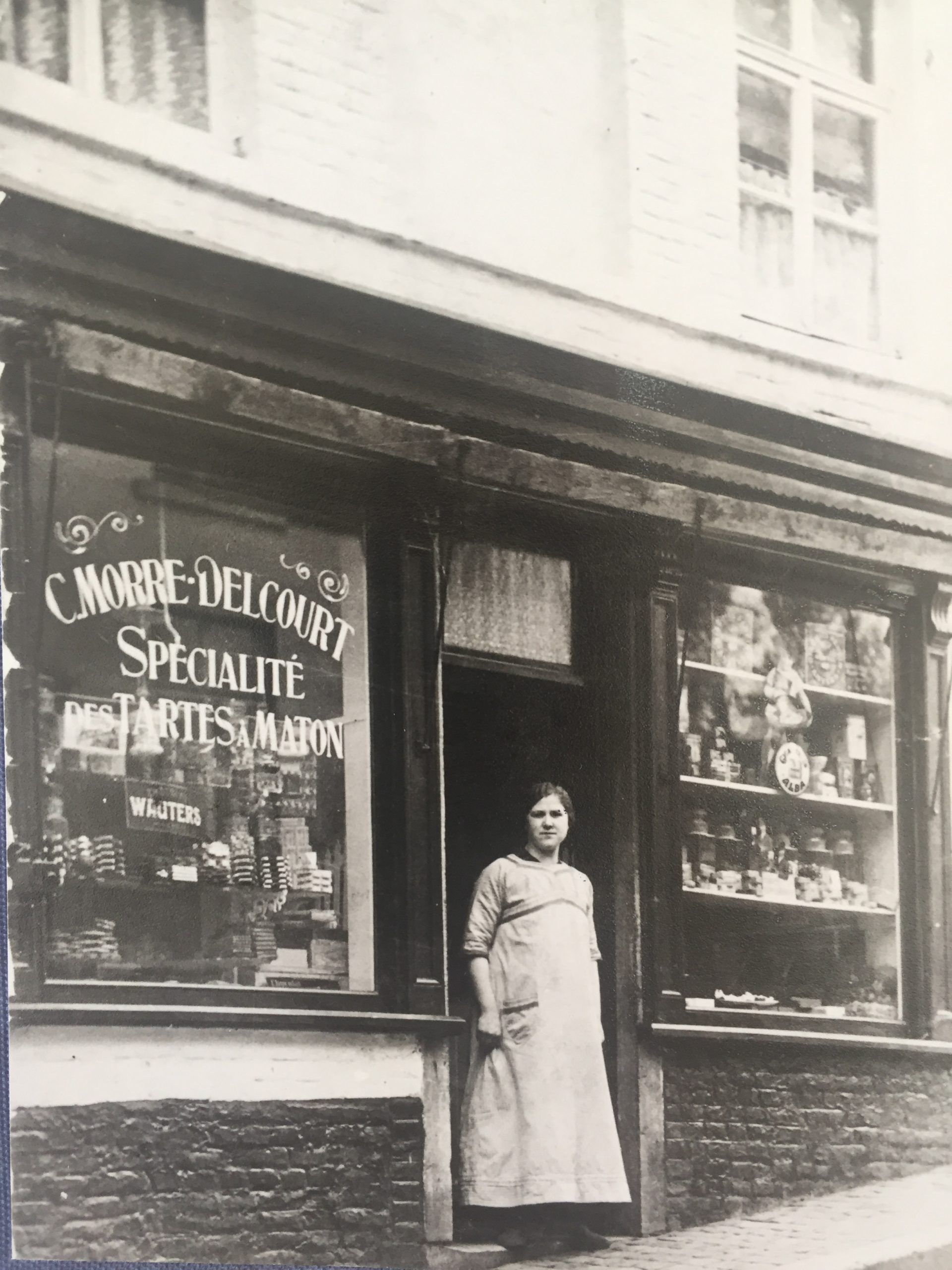

Matten have been produced here since the Middle Ages, eaten more as porridge than as cake and rarely containing sugar and eggs. There’s a recipe for mattentaart in cookbooks from 1510 (Thomas van der Noot’s “Boeken van cokerijen”) and it’s claimed by Geraardsbergenaars, somewhat hopefully I suspect, that cakes seen in 16th century artwork such as Peter Bruegel’s famous painting De Boerenbruiloft (The Farmer’s Wedding) are in fact mattentaarten. It was largely a homemade product, traditionally baked for family occasions by the mother of the home. Evidence of a shift to buying mattentaarten in bakeries only came in the late 1800s when the town’s commercial baker Johannes Franciscus Morre baked and sold mattentaarten on the Grotestraat. There’s a famous photo dating to 1912 rubber stamping this transition by showing a sign on the Morre bakery with the inscription: “Old Maison Morre: Specialty of Mattentaarten”.

One of the reasons the Mattentaarten of Geraardsbergen are so special, say Geraardsbergenaars, is that the grass from the Dender Valley has a specific profile and thus contributes to a milk with unique characteristics, in turn differentiating the taste of the matten. A research paper from Biologist Eric Cosyns confirms that this is possible, and offers interesting insights into the history of agriculture in the region, but there seems to be no single defining scientific source that categorically links a special type of mattentaart to the location of the town. Johan De Froy mentions the unique terroir argument during our chat, but I’m not sure from his tone whether he truly believes it himself. He also mentions that there are fewer and fewer matten farmers in Geraardsbergen, and it’s the first time on my trip that I become concerned about the future of the Geraardsbergse Mattentaart.

Before I leave Bakkerij De Vesten, De Froy tells me that there is an organisation in the town charged with promoting the cake of which he is a member. Arne De Wilde is a member too. As is Olav Geerts. The organisation is called “De Broederschap van de Geraardsbergse Mattentaart”—“The Brotherhood of the Geraardsbergse Mattentaart”. Their mission is to “perpetuate the region of Geraardsbergen as the genuine cradle of the Mattentaart.”

I learn that the Brotherhood has a “Prince”.

And it turns out the Prince has a phone number I can call.

III: The Brotherhood

The Prince of the Brotherhood of the Geraardsbergse Mattentaarten is Roger Flamant, who lives with his wife Irene De Smet in a residential area on the higher hills at the edge town. Flamant will turn 100-years-old in January. It becomes apparent on our call that neither Flamant nor De Smet speak a word of English, but through my limited, garbled Dutch, I manage to secure an invite.

When I arrive, freshly baked mattentaarten are pulled out of the oven. They’re plated up on the back terrace, with orchards and meadows stretching out for hundreds of metres in front of us, some located in Flanders and some in Wallonia.

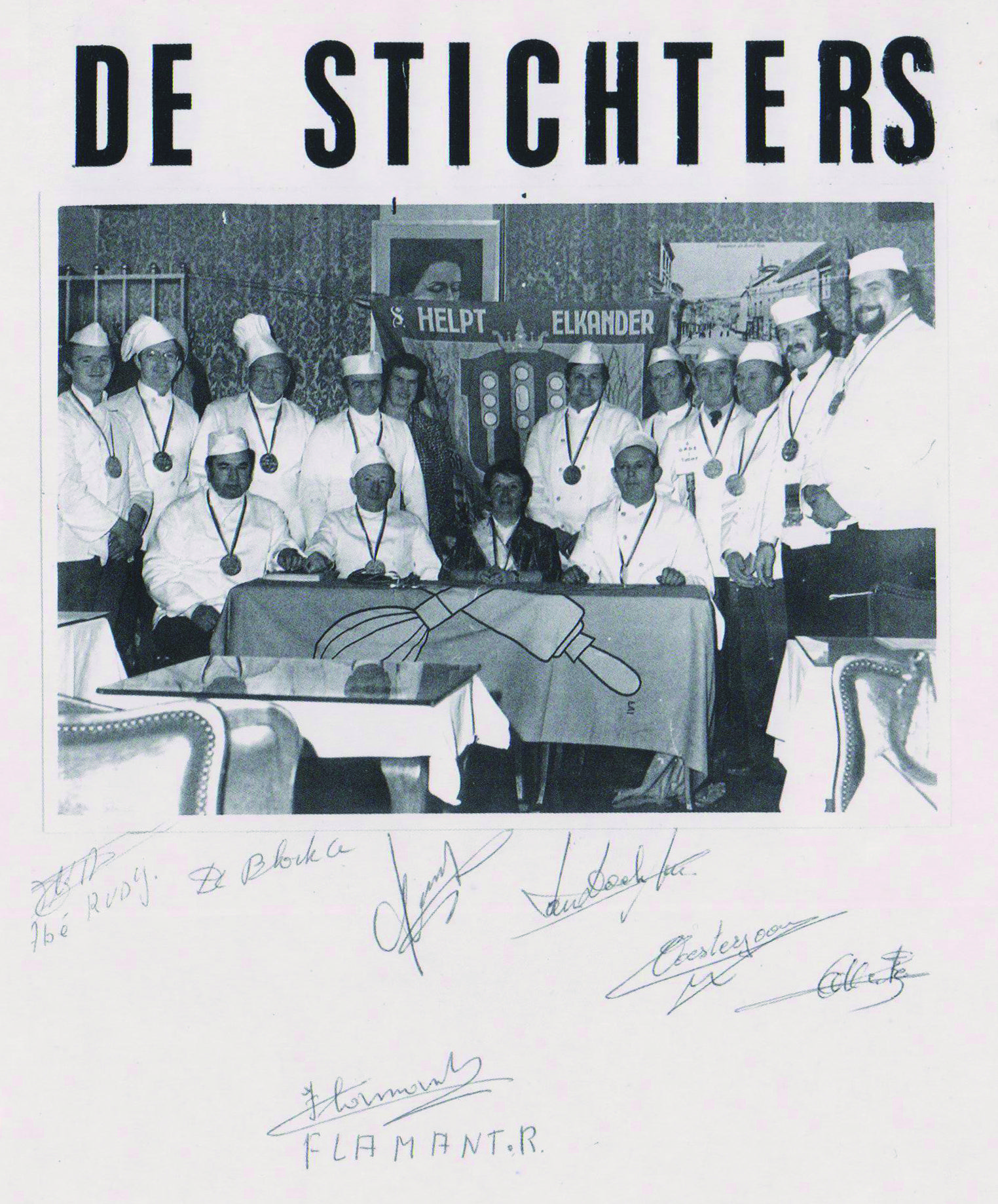

Flamant and De Smet tell me that they worked as bakers in Geraardsbergen for most of their lives, on De Vesten, where Johan De Froy now has his bakery. In 1978, they discovered that a group of Walloon bakers, just across the language border in Flobecq, had created Le Confrérie de la Tarte au Maton, their own Brotherhood of the Mattentaart. Alarmed at the potential of Geraardsbergen losing a central place in the cake’s story, Flamant and De Smet were among a group of Geraardsbergen bakers who, on 17 September 1979, founded the Brotherhood of the Geraardsbergse Mattentaarten. Their activities were diverse and, as it turns out, highly effective.

The Brotherhood organised the first “Dag van de Mattentaart” (“Day of the Mattentaart”) in 1980, an event which was opened by dignitaries including the Town Mayor and a “Mattentaart Princess”. A huge tent was erected in the market square. One bakery, Bakkerij Vercleyen, sold 24,000 mattentaarten in one day alone. The Day of the Mattentaart still takes place every year, in April, with tastings, and demonstrations, and a ceremony to induct new members into the Brotherhood.

The Brotherhood campaigned for the mattentaart to appear on the national postage stamp, and in 1985, it became the first ever regional dish to be depicted on a Belgian stamp. 3.2 million mattentaarten stamps were printed for circulation. The town of Geraardsbergen bought 40,000 of them in the first two days of their being printed.

Top right: The Founders of the Brotherhood of the Geraardsbergse Mattentaart in 1979. / © Photo: Collectie Roger Flamant

Bottom: Scenes from the Dag van de Mattentaart in 1988. Irene De Smet and Roger Flamant are pictured on the right. / © Photo: Collectie Roger Flamant

The Brotherhood secured world records. On 16 April 2000, Geraardsbergen paraded a massive mattentaart on its market square. Fifteen bakers used 2,000 eggs to create a mattentaart which weighed 536 kg, and measured 13 metres in length and 1 metre in width. It was certified by the Guinness World Records as the largest mattentaart ever baked in Belgium. It was cut into pieces and sold to the public, completely eaten within 100 minutes.

The Brotherhood landed some well-known inductees. Some of its most famous members included sportspeople (Guy Thijs, the most successful manager of the Belgian football team in history), politicians (Government Minister Herman De Croo, the father of current Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo) and scholars (Geraardsbergse poet Marleen De Smet, whose erotic poem “Tepeltaartje” or “Nipple Cake” compares the small crust on the top of the cake to a nipple).

Right: Irene De Smet and Roger Flamant pose with the certificate from the Guinness World Records for the largest mattentaart baked in Belgium.

Flamant and De Smet show me newspaper clippings and pamphlets relating to all of these accomplishments, but the thing they are most keen to tell me is what is considered by the people of Geraardsbergen to be the greatest achievement of the Brotherhood.

In 2007, after a four-year application process by the Brotherhood, the Geraardsbergse Mattentaart was awarded a “Protected Geographical Indication” under EU law. PGI emphasises the relationship between the specific geographic region and the name of the product. It became a legal offence then to use the term “Geraardsbergse Mattentaart” unless you played by the rules. You could still use the label if you bought the unbaked raw mattentaart from a baker in Geraardsbergen or Lierde and baked it in another town. But the matten always had to originate in the region. And the cake always had to be prepared there too.

The Geraardsbergen Mattentaart was the first ever regional Flemish food product to receive European recognition and protection. The announcement resulted in an explosion of media coverage for the town of Geraardsbergen and for the local mattentaart. Tourism benefited. Most importantly, the protection allowed bakers in Geraardsbergen and Lierde to increase the price of their mattentaarten, and it precipitated a huge boost in their sales.

The bakers were thriving. The city leaders were delighted. And the townsfolk were proud. But back on my visit, as I thank Roger Flamant and Irene De Smet for their hospitality and drive back towards Geraardsbergen, it strikes me that there is one group of people who seem to have been largely ignored in the mattentaarten conversation; one group of people with whom I am yet to speak. If the Brotherhood is the history of the Mattentaart, then its future lies in the hands of the farmers.

IV: Matten

Everything—the livelihood of the bakeries, the existence of the Brotherhood, the protected status of the cake—hinges on the production of matten, curdled milk from local farms. It is the cake’s agricultural base ingredient; its major flavour contributor; its connection to the land.

On the list of farmers I have secured from the Brotherhood, it turns out that many are dead or that their families have left the business. There are just eight farmers left producing matten for all of the Geraardsbergse Mattentaarten.

Lynn De Bruyne, thirty-one years old, is dressed in shorts and hoodie, with ash-blonde hair tied back in a ponytail, and red-cheeked, healthy skin earned from a life spent outdoors. She has a three-year-old daughter, Francis, and lives across from her father’s house, a few hundred metres from the farm on a country lane on the outskirts of Geraardsbergen.

Her father does not produce matten anymore, focusing instead on the busy work of dairy farming, and so Lynn De Bruyne produces matten on her own, seven days a week, on top of her other job at the meat counter of large supermarket chain Colruyt. Sometimes she’ll ask her aunties or her 83-year-old grandmother to go and check on the matten if there is an emergency at school with Francis, or if she has to fill in shifts for others at Colruyt. But mostly, she does it alone.

De Bruyne takes me to see the cows grazing on her land, a field of 20 hectares a little further down the country lane. The majority of the milk from the cows is sold to milk companies such as the Olympia Creamery, but 10% of the milk is kept back for the matten. The milk is heated to 85°C using a small gas furnace back at the farm, before vinegar is added. It’s then stirred for a few minutes until the milk curdles. The wet curd is then hung in muslin bags—cloth sacks with very fine holes—for one full day, after which the drained curd will be ready to sell as “matten”.

Lynn De Bruyne is busy. She tells me that on a normal day, she’ll produce around 240 kgs of matten, but that on Saturdays, she has a regular customer who takes as much as 400 kgs. In order to try to make the production of matten at the farm more sustainable, De Bruyne raised the prices of her matten on 1 March 2021 from €4.00 per kilogram to €4.50 per kilogram, but met resistance from bakers. People are consumed with their own business, their own costs, their own challenges. “They don’t know how much work there is,” says De Bruyne. “They think it just appears.”

There are a number of other tensions. Towns nearby remain disgusted that they have been excluded from the EU geographical protection. There have been wars of words about the cake between the Mayor of Geraardsbergen and the Mayor of neighbouring town Horebeke. The Walloon mattentaarten bakers are similarly disgruntled. “Ellezelles, for example, has a great tradition of mattentaarten going back decades,” says Arne De Winde. “That’s tough for them. But it’s all about being the first. It was kind of a race against the clock.”

There are also worries that the EU Label might be hijacked by an industrial food company who would set up in Geraardsbergen to produce mass quantities of “Geraardsbergse Mattentaarten”. Part of the charm of the mattentaart, which relates to its origins as a homemade grandmother’s cake, is that it is baked in small batches by local artisans, and not produced on an industrial scale with, for example, drier matten and added cream. Companies like Expomat, a large industrial bakery in the nearby town of Zottegem who produce over 6 million mattentaarten each year, have expressed their interest in exporting to China and securing Labels which help them do so.

But the diminishing number of matten farmers is the biggest issue, one of which the Brotherhood and the bakers and the politicians and the tourism authorities are all aware. It’s not solely the town’s fault. Small farm holdings are becoming endangered the world over, as farmers work part-time jobs outside of farming to make ends meet as their children are driven into less time-consuming and financially more rewarding professions. Geraardsbergen will soon be launching a project “Van wei tot wij” (“From whey to we”), in which they work with farmers to create new products from the residuals of the matten: whey. This will certainly add a revenue stream for farmers, and it will create a network of social entrepreneurs keen to work with farmers in a circular economy. Whether it’s enough to stem the changes in the global agricultural industry and sustain the livelihoods of local farmers into the next generation remains to be seen.

Lynn De Bruyne is working two jobs, seven days a week, while trying to raise a family and make things work. She wants to continue. But there’s a chance that matten production will become unsustainable for her to the point that she will have to stop. Geraardsbergse Mattentaarten is an EU protected term, but with fewer and fewer matten farmers every year, and nobody to replace them, there may soon be nothing to protect.

Geraardsbergse bakers may soon have to buy matten from other regions outside Geraardsbergen and Lierde to make their mattentaarten, but then they wouldn’t be making Geraardsbergse Mattentaarten. And that would equate to the town’s biggest defeat of all.

V: Thrown Away

The final event every year on Geraardsbergen’s Dag van de Mattentaart is the “Mattentaartenworp”—the “Mattentaart Throw”. Members of the City Council and other digatories stand on the steps of Sint-Bartholomeus Church, in the market square near to the Manneken Pis. The councillors speak with great pride and gratitude of the cows and the farmers and the bakers, before throwing mattentaarten into the hundreds-strong crowd who are standing below them in the square. These days, the mattentaarten are wrapped in individual plastic packaging so the townsfolk can eat the ones they catch. Importantly, there’s a golden mattentaart amongst those thrown, one handcrafted by a local goldsmith using a freshly baked mattentaart as a model, with various gold plates welded and shaped together. The person who catches the golden mattentaart wins a cash prize and the town’s respect.

The mattentaart is worth fighting for not only for its wonderful food qualities, but because Geraardsbergenaars have put themselves into this little cake. They’ve constructed a history of the mattentaart which is attached to their town, purporting to see the cake in old paintings, and proposing arguments about the uniqueness of the region’s milk.

They’ve claimed the mattentaart as their own through EU recognition, with rules about how it can be made and who can make it, rules which serve to differentiate their tribe from those of other towns. They’ve accumulated their own language around the cake—“nis” and “roosje”—as well as cultural depictions in artefacts, songs, erotic poerty, and cartoons.

The throwing of the Mattentaart at the end of the Dag van de Mattentaart is absolutely an eccentric tradition. But it’s also a shared ritual the Geraardsbergenaars have built together which transforms this simple little cake into a gravitational centre for their sense of identity. By throwing the cake into the crowd, the leaders of the town are initiating an act of communion, one which represents the sharing of memories, experiences, relationships, and values which Geraardsbergenaars hold together.

With fewer and fewer of their farmers producing matten each year, claims to ownership of the cake from other regions, and threats to the artisanal nature of its production, Geraardsbergenaars thus find themselves in a battle for their identity. The Muur is a glory lost, the memories of great cycling races of the past still discussed in whispers tinged with sadness throughout the town’s cafés. In contrast to the masculine bravado of the Brussels statue, the Manneken Pis here stands as another lost glory, irreverent and whimsical. The statue’s demeanour embodies the attitude of the marginal, averse to the rules that apply in the centre. This is a town in-between things, but belonging to none of them. However, the mattentaart is still theirs. For now, catching a golden mattentaart in “M Town” still means something. For much how longer will depend on what Geraardsbergenaars do today.

*

Mattentaart Recipe

Mattentaart is a small, sweet cake of around 8 cm in diameter made from a filling of curdled milk (the matten) mixed with eggs and sugar, and encased in a golden yellow puff pastry exterior.

Ingredients

- 2 litres (68 fl oz) of whole farm milk

- 60 centilitres (20 fl oz) of buttermilk

- 4 eggs

- 400 grams (14 oz) castor sugar

- 2 large sheets of puff pastry

- Knob of butter

- Pinch of flour

Directions

- Produce your “matten” by bringing to the boil 2 litres (68 fl oz) of whole farm milk in a saucepan on the hob. At the boiling point, add 60 cl (20 fl oz) of buttermilk. When the milk has curdled, scoop the solid mass—the matten—into a muslin cloth and hang to dry for ~12 hours. Afterwards, grind the matten with a meat grinder or food mill so you should be left with ~300g of matten.

- To create your mattentaart filling, separate the eggs and mix the yolks and the sugar with the matten, and then gently fold in the beaten egg whites.

- Place greased baking moulds next to each other and cover them with a sheet of puff pastry. Press in the pastry to fill the moulds (rub with the butter and sprinkle some flour). Use a spoon or piping bag to put in the filling and cover with another sheet of puff pastry. Press the top and bottom sheets together so the pastry is closed.

- Brush with beaten egg and use a pair of scissors to cut a small hole or incision in the middle of the top layer so that the vapour can escape and to create the typical “rose”.

- Bake at 225°C (~437°F) for around 30 minutes. Let cool for several minutes before serving.