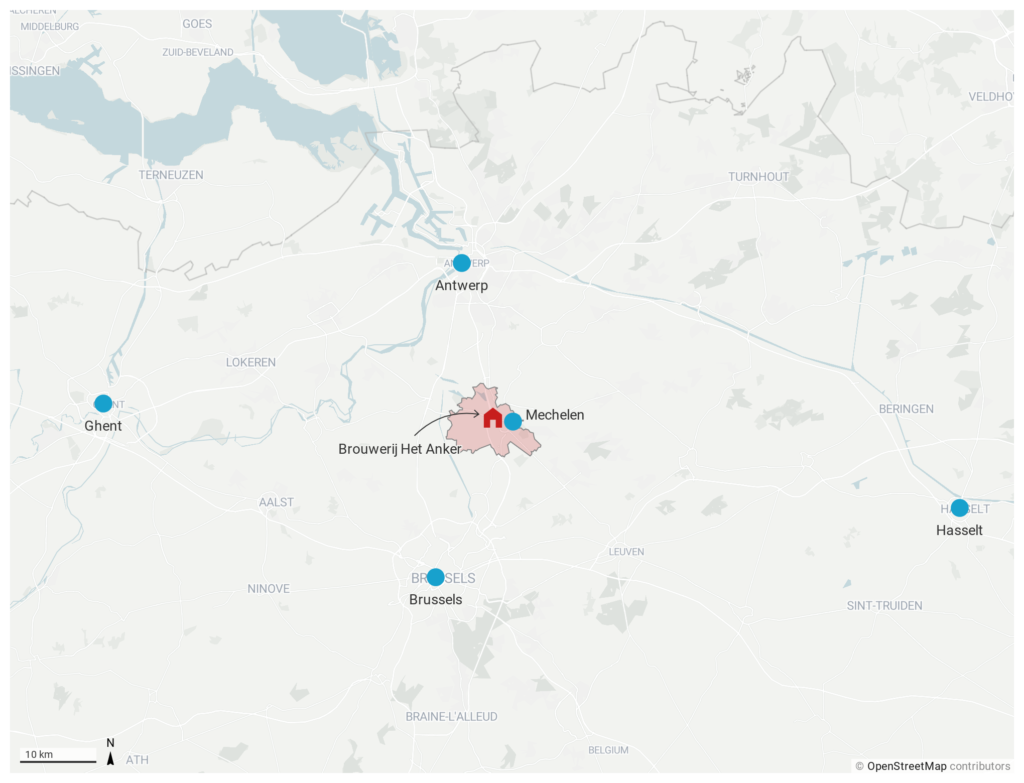

In 1990, Charles Leclef inherited his family brewery in Mechelen in a state of disrepair and on the verge of bankruptcy. In his quest to turn around Brouwerij Het Anker’s fortunes, he discovered the importance of people and the power of their pride.

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

It is said that on the night of 27 January 1687, a man under the influence of several beers stepped out of a café in Mechelen, a Flemish city which lies equi-distant between Brussels and Antwerp. Looking up, the man saw yellow-reddish lights and smoke emanating from the top of the city’s cathedral, Saint Rumbold’s, the jewel in Mechelen’s architectural crown. The man alarmed the neighbours and the City Council was called in haste, organising an effort to extinguish the blaze above them. Buckets of water were passed hand to hand by Mechelaars ascending the tower stairs in one long chain as they frantically tried to douse the flames.

But at the top, there was no fire. What they thought had been smoke was the backlit haze of a full moon’s yellow-reddish glow shining brightly behind low clouds. It was all a terrible mistake. In the following days, the city’s inhabitants tried to keep the event a secret, but soon Brusseliers and Antwerpenaars found out what had happened and ridiculed the Mechelaars for their drunken stupidity. They called inhabitants of Mechelen the “maneblussers”, or “moon extinguishers”, a slight which, three hundred and thirty four years later, is still used as a nickname for Mechelaars.

Charles Leclef is a Maneblusser. He is tall, moderately built, and dresses smart casual. He sports a mop of floppy dirty-fair hair, and a relaxed, disarming demeanour. He was born and bred in Mechelen, and grew up on the grounds of his Uncle’s brewery, Het Anker, on the city’s Guido Gezellelaan.

There had been other breweries in Mechelen, as many as thirty, but by the early 1980s, even a large brewing company such as Brouwerij Lamot, once a lager behemoth, had been picked off by ambitious giants Bass and Piedboeuf, with production moved away from the city in 1994. Het Anker was soon the last remaining brewery in Mechelen.

When Leclef was a child, Het Anker’s Belgian Dark Ale, Gouden Carolus, was one of the most respected specialty beers in Belgium. Charles Leclef’s grandfather Charles Van Breedam had named the brand after Emperor Charles V who ruled Europe from Mechelen in the 1500s (it was also the name of the golden coins the Emperor designated as currency in the city). But Leclef’s grandfather Charles Van Breedam died unexpectedly, at the age of 62. His successor was Leclef’s uncle Michel Van Breedam, who despite being a competent brewmaster, did not possess strong management skills. The brewery fell into disrepair. The beers suffered, as did the reputation of the brewery.

Mechelen was once the seat of European power in the Middle Ages, with rich histories of tapestry and lace, wood carving and sculpture, and the carillon musical instrument. It boasted fabulous architecture—there are more “listed” buildings per square metre in Mechelen than in Bruges. But Mechelen itself was in poor health at the time Michel Van Breedam owned Het Anker. The city boasted numerous negative records such as the dirtiest city in Belgium, and the city in Belgium with the highest crime rate. One international organisation wrote that it was a “blot” on the Belgian landscape.

In 1990, when Charles Leclef was just 24 years old, his uncle Michel Van Breedam stood down from running Brouwerij Het Anker. Michel’s children—Leclef’s cousins—had no desire to take the brewery on, mostly because the brewery was run-down and worn-out, in financial ruin, and on the verge of filing for bankruptcy. Sources at Het Anker describe the brewery at that time as being “clinically dead”. The Belgian broadsheet newspaper De Tijd wrote that the site of the brewery was “een kankervlek in de stad”: “a cancer stain on the city.”

The family toyed with the idea of asking an outsider to buy the brewery. Charles Leclef was concerned. “But then the soul would be away,” he said. In 1990, after completing studies in Applied Economic Science at KU Leuven, Charles Leclef took over because no-one else in the family would, becoming the fifth generation of the Van Breedam-Leclef family to lead Brouwerij Het Anker. If Charles Leclef failed to save the brewery, it would mean an end to 118 years of family heritage. Most importantly for Charles, it would be a kick in the gut to all those city inhabitants who had worked at, partnered with, and supported Het Anker across Mechelen. Their pride was on the line. The maneblussers were tired of being a laughing stock.

When Charles Leclef took over Het Anker in 1990, he inherited its history. In the 1400s, a semi-monastic community of religious women—the Mechelen “Beguinage”—brewed beer on the site to comfort the sick and dying who were in their care. When they eventually vacated the buildings in 1865, it was taken into the ownership of Louis Van Breedam (Van Breedam was the surname of Leclef’s mother). The name of the brewery translates literally as “The Anchor” and there are several stories about the name’s provenance. One is that it is a maritime reference to the sea port of Antwerp. Another is that it comes from the Dutch verb “verankeren”, meaning to firmly secure in position or provide a basis or foundation. Most likely is that it was as a mark of respect to the famous Mechelen maltster and brewer of the 1300s, Jan In Den Anker.

Leclef also inherited the catastrophic problems of the brewery, especially relating to neglected production equipment and inadequate financial planning. Faced with the challenge of how to save Brouwerij Het Anker, young Charles Leclef vowed to draw upon the history of the brewery, and the pride of Mechelaars. He entered into short-term commercial brewing relationships with other breweries (with Riva between 1991-1993 and John Martin between 1995-1997) so that he could scrape together enough finance to improve the brewing and packaging equipment. It required intelligent negotiation and people skills. As a brand building exercise and additional source of income, he opened Het Anker to visitors at a time when few breweries in Belgium were doing so (last year, pre-COVID, Het Anker was receiving 35,000 thousand visitors per year).

Importantly, Leclef doubled down on the Gouden Carolus, renaming it Gouden Carolus Classic and introducing a range of line extensions in the 2000s, including Gouden Carolus Tripel, Gouden Carolus Ambrio, Gouden Carolus Hopsinjoor, Gouden Carolus U.L.T.R.A., Gouden Carolus Christmas, and Gouden Carolus Indulgence.

In 2009, Leclef introduced a Belgian Blonde Ale of 5.8% ABV to the line-up, an easier-drinking, more approachable option for those who might find the Gouden Carolus Tripel too intense as an everyday beer.

He called it Maneblusser.

Every year on 24 February, the birthday of Emperor Charles V, Het Anker brews a special high alcohol ale called Gouden Carolus Cuvée van de Keizer Imperial Dark—the “Grand Cru of the Emperor”, a beer that would garner a cult-like following. One variant, the Gouden Carolus Cuvée van de Keizer Whisky Infused, would win the “Consumers Trophy” of the annual Zythos beer festival in Belgium on three consecutive occasions. The feat demonstrated that Het Anker could not only provide the everyday beer for the working Mechelaar like the Maneblusser Belgian Ale, but the brewery could also serve as the darling of the beer geek.

It was not easy, but LeClef brought the brewery back from the brink. The Mayor of Mechelen since 2001, Bart Somers, had known Leclef since they were children, and had seen how Leclef had saved Mechelen’s brewery and beers, bringing pride back to its inhabitants in the cafés of the city. He saw that Leclef’s business connections and negotiation skills would be an asset to the City Council of Mechelen. And so in 2012, Somers asked Charles Leclef to run in the election for the City Council. But Leclef wasn’t a politician. And he didn’t want to align with any political party. And besides, he was way too busy managing his family brewery. Het Anker was in need of renewed equipment again, in the brewhouse and the packaging hall, and Leclef needed to find a way to secure additional finance.

In 2016, a Dutch private equity investment group called Waterland offered to invest large sums of money in Het Anker in exchange for a stake in the business. Waterland were creating a portfolio of respected Belgian family breweries such as the producer of Tripel Karmeliet—Brouwerij Bosteels—in which they had already acquired a large stake. The pitch to Leclef was that Het Anker would occupy a key position in that portfolio.

Leclef did need the funds but did not feel comfortable partnering with Waterland. Instead, he asked for a meeting with his bank, BNP Paribas Fortis, with whom Leclef had forged a strategic financial partnership over thirty years. Reflecting on family mistakes of the past, Leclef struck a deal with BNP Paribas Fortis to ensure financial stabilty which would give the bank a minority shareholding in Het Anker in exchange for the investment. Leclef trusted BNP Paribas Fortis and because of the ongoing relationship, could openly build into the deal a clear exit strategy, as well as protections for the family ownership of Het Anker.

After Waterland pitched to several Belgian family brewers, it became clear they would be unable to establish the portfolio group they wanted. The family brewers all said no. So Waterland did what venture capitalists do: they off-loaded Bosteels to the highest bidder. In this case, Anheuseur Busch Inbev, the largest brewing company in the world, became the full owner of Bosteels through its ZX Ventures division. Bosteels had little choice at that point but to acquiesce to new ownership. It was the end of 225 years of family ownership for the Bosteels family. Het Anker, on the other hand, had avoided that fate and continued to grow slowly and steadily, remaining in the hands of the Leclefs.

These discussions about capital and returns on investment led Leclef to reflect on the disparity of opportunity in the brewing world, but also inequities in the society in which he lived. Het Anker had been able to turn its fortunes around through the good will of people who had helped him in the early days, the hard work of his employees, and the pride the Mechelaars had in the brewery of their city. People mattered more than anything else and Leclef often saw people being treated unfairly.

At meetings with other brewers, Leclef would be asked about his volume of production in hectolitres, and his growth figures, and his turnover numbers, parameters about which Leclef felt more and more disinterested. “Most of the entrepreneurs and business people are only thinking about themselves all the time and say ‘what can I do to have more?’,” says Leclef. “But economics is in the function of people, not the other way around.”

Around that time, Leclef decided to publish statements which demonstrated Het Anker’s re-focussing not on financial gain, but on the relationship between the brewery and the people working for and with it. “Het Anker aims to be a company that everyone is proud of,” read the new mission statement. The new vision statement noted both the words “proud” and “pride.” In the Standards and Values section, the word “Pride” featured again.

Het Anker’s focus on people and their well-being contrasted with what Charles Leclef saw in politics and business. At the same time as he was strengthening his reputation as an entrepreneur by developing new initiatives at Het Anker, Leclef was becoming more publicly outspoken on social issues such as poverty, racism, and climate change. On his personal Facebook page, he posted videos of Alexandria Osario Cortez, quotes from Nelson Mandella, and talks from Greta Thunberg. Soon, he turned his attention to changing mindsets in Belgium’s beer industry.

Charles Leclef’s charming nature and Het Anker’s growing commercial influence ensured he became a leading figure in the Belgian Brewers Federation, an association established in the 14th Century. The Federation’s members include well-known family concerns such as Duvel Moortgat and Brasserie Dupont, all the Belgian Trappist breweries, the majority of Lambic producers, as well as AB InBev and Alken-Maes. (Leclef was chosen to serve a three-year term between 2011 and 2014 as “Grandmaster of the Knighthood of the Brewer’s Mash Staff”, a largely ceremonial role at the head of the Federation which would see him representing the organisation at national events such as the Belgian Beer Weekend in Brussels’ Grand Place each year).

But despite being responsible for the vast majority of beer produced in Belgium by volume, members of the Belgian Brewer’s Federation made up only a quarter of the number of breweries in the country. In addition to an outdated system of membership fees based on archaic excise calculations and large annual production capacities, the rules stipulated that breweries wishing to join should be at least five years old and first be proposed to the board for acceptance by two current members of the Federation. At a meeting of the Federation in early 2018, Leclef suggested they reach out to these newer, smaller, contemporary breweries. No-one in the Federation offered to lead the project. Seeing that nothing was likely to happen, Leclef volunteered to do it himself.

In 2018, Charles Leclef travelled all around Belgium on his own, personally visiting 94 breweries who were not members of the Federation but who had answered his call. “Leclef’s approach was humble,” says Olivier De Brauwere of Brussels Beer Project. “He was clearly there to listen to us. He is an open-minded person.” Leclef presented his findings to the Federation and suggested changes which would make it more fair for smaller breweries to be part of the Belgian brewing landscape.

Impressed by his comprehensive report and passionate presentation, the Belgian Brewers Federation accepted all of Leclef’s suggestions, scrapping the rules requiring the need for a brewery to be at least five years old before it became a member, as well as the requirement for members to have a minimum annual production amount. Breweries wishing to join the Federation would no longer need to be proposed by two existing members. Instead, it was decided that different categories of membership would be created based on hectolitre production. More breweries would have their voices heard.

The changes prompted a spate of smaller breweries to join the Federation for the first time. Forty-six breweries joined as new members as a direct result of Leclef’s visits. If such outreach could yield a fairer situation for smaller breweries, perhaps there was a way that a more open dialogue in politics and business could lead to a fairer way of life in Mechelen?

Leclef doesn’t like the term “giving back”—“If you think ‘I have to give back’, you probably took too much,” he once wrote. But when Bart Somers asked him to run for the City Council again, this time on the 2018 ballot, Leclef reconsidered. He agreed to his name being listed on the ballot alongside 260 other names, vying for one of 43 spots on the Mechelen City Council. He was running, not with any political party, but as an independent. To improve his chances, he entered a campaign coalition with other independents, the Greens, and the Open VLD (Liberal Democrats). Having never been involved in politics before, he had no idea of his prospects, but Leclef would see it through. “I want to reinforce my commitment to the city,” he said.

The election of the Mechelen City Council took place on 14 October 2018. Charles Leclef received the 25th most votes out of the 260 candidates and was duly elected. He was at the city hall and heard the results when they came in, drinking a Gouden Carolus with colleagues and friends to celebrate. Bart Somers topped the poll, extending his run as Mayor of Mechelen. Leclef’s term on the City Council extends until 2024. His impact would mainly be in the role of facilitator, offering what he describes as “an objective way to look at things.”

A few days after the election, he publicly launched a new “ideology” which he called “Fairism”, something he describes as “a fair way to organise societies”. The name comes from other “isms”—liberalism, socialism, capitalism—none of which Leclef believes ensure a fair society. One of Fairism’s main principles is that of limiting capital, where people must accept that there is a fair limit to their personal assets. In 2019, he published a book entitled “Fairism: an equitable form of coexistence” which set out the five pillars of the ideology: Transparency; Commitment; Basic rights; Value; and Freedom of Choice.

Fairism has been met with intrigue as well as confusion. In interviews with the Flemish media, Leclef has been asked why the complex machinery of Belgian politics needs yet another political ideology. They have suggested to him that he is perhaps too naive. Leclef responds with a question: “Gaan we tegen de muur blijven lopen?” (“Are we going to keep going up against a brick wall?”).

Het Anker continues to grow with Charles Leclef at the helm. In the years in which he took over in the 1990s, the brewery produced roughly 1,300 HL of beer per year, brewing one time each month. Last year, Het Anker brewed 45,000 HL of beer, brewing 420 times in the year. It enjoys a turnover of 15 million euros. Not only did he bring Het Anker back from the brink, but he invested in a range of initiatives such as the brewery restaurant, a robust visitor infrastructure, a hotel on site, and a whiskey distillery located on a 17th Century farm in Blaasveld to the North West of Mechelen. He also invested in people: Het Anker has 90 employees. Leclef’s son William Leclef is now involved in the brewery with a view to succession in the future.

In 2020, Brouwerij Het Anker won a tender to buy a small church in the Mechelen suburb of Battel. Sint-Jozef church sits right next to the Leuven-Dijle canal, a stretch of water traversed by walkers and cyclists. Leclef’s plan is to convert the church into a microbrewery, microdistillery, and restaurant. “Batteliek” is set to open later in 2021. After Het Anker won the tender, Leclef reflected on the fairness of the deal. “Who am I to say because I can find some money, I have all the rights,” he says. “If in a few years, I cannot realise the project because it’s not possible or it’s not working, I still have all the rights [to the church]. That’s not fair.”

Leclef encouraged the community of Battel to establish an association, and several hundred inhabitants joined. He then gave the Battel community association a right of pre-emption should Het Anker sell the property, without them having to put money on the table. It’s an example of the type of “co-existence” between business and community which might appear as a story in his book “Fairism”.

A few months ago, Het Anker opened a new restaurant project in the city centre at the foot of St. Rumbold’s Tower, the most iconic architectural building in Mechelen. At “De Thien Gheboden” (“The Ten Commandments”) customers will be able to choose how much they pay for a meal. Leclef is clear that it’s not a charity, and that, like any business, it will live or die on its ability to turn a profit. The idea is that customers who are willing to give more will compensate for those who have less.

From the terrace of the new restaurant, no matter how much you decide to pay, you can look up to the top of St. Rumbold’s Cathedral and see the tower where, according to folklore, the Mechelaars of 1687 tried to put out the nebulous glow of the moon. The “Maneblusser” nickname was concocted by Brusseleirs and Antwerpenaars trying to shame the Mechelaars and make a joke at their expense. Interpreted differently, however, the tale is also about the honour of the city. The Mechelaars saw their beautiful cathedral in jeopardy and everyone jumped into action to save it. That sort of civic pride might facilitate the type of equitable co-existence of which Charles Leclef dreams. And it’s a pride that might be impossible to extinguish.

*