It seemed a no-brainer. A new restaurant which centred around beer. In the city that’s home to the world’s largest brewery. In a country that deifies beer and brewing. From an award-winning beer chef. But, in Belgium, nothing is ever quite as simple as that.

Words and photos by Eoghan Walsh

Edited by Breandán Kearney

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Food Group” series. Read more.

On the morning of 16 May 2018, Bram Verbeken hopped on his bike and cycled from his restaurant Hop Gastrobar at Leuven’s Vaartkom, past the treacly Dijle river, pulling up at a small newsagents on the Mechelsestraat. A friend had called Verbeken that morning, to let him know that this particular week’s edition of Knack Weekend, one of Flanders’ main weekly periodicals, featured a review of Hop Gastrobar.

Normally, like most chefs, Verbeken would say he didn’t care what the papers wrote about his restaurant, so long as his customers were happy. Business was ticking along since he’d opened Hop Gastrobar the previous February. But it was sometimes a difficult proposition to lure Leuvenaars away from the city centre to his canalside outpost on the edge of town, in the shadow of the city’s crumbling, decommissioned Stella Artois brewery.

Bram Verbeken wasn’t just a chef now. He was a restaurant owner, in an industry where new eateries have a notoriously short shelf life. Verbeken had quit a steady job at Zarza, one of Leuven’s most highly-rated restaurants, leaving a kitchen he’d led to wide acclaim for several years with only an idea in his head of a new kind of restaurant.

Hop Gastrobar would bring together two passions Verbeken had incubated in a decade in the kitchen, undervalued and unloved, but in his eyes, unmatched: locally-sourced Belgian ingredients; matched with a beer list that took its lead from a new wave of artisanal and small-scale Belgian breweries eager to explore the wilder, less conventional side of beer.

Think a tough and muscular cut of Belgian pork shoulder, marinated for 24 hours then cooked for a long time at a low temperature, crusted on the kitchen’s flat top and then thrown in the barbecue for a good smoking. The result: a beautifully tender, intensely flavoured piece of meat. Plated up for a diner and paired with a bright mixed fermentation beer-cider blend from Antidoot Wilde Fermenten, or a tart, funky and fruity Oude Geuze from new Lambic brewery Lambiek Fabriek, or a citric, juicy IPA from Brussels brewery L’Ermitage. Starters would be replaced by “bites” or small plates, and the four-course menu would be seasonal and take-it-or-leave-it. There would be no à la carte dining here.

Hop Gastrobar would be a restaurant for people who wanted to eat unfussy food with an echo of their Belgian roots, presented in a casual but attentive environment, and served with beers intended to challenge as much as conform to their expectations.

As much as Verbeken hoped a positive review from Knack would lead to more bookings for Hop Gastrobar, what he was really seeking was validation: that the gamble he had launched into two years previously was worth it; that he could convince his diners to love traditional, unsexy Belgian ingredients as much as he did; that food could be presented in an accessible but aspirational setting; and that Leuven—a town which had fallen out of love with its brewing heritage—would embrace a restaurant with beer at the centre of its identity.

In his time at Zarza, Verbeken had explored the best of what Belgian terroir had to offer, deepening his passion for presenting local ingredients in their best light. At Zarza he had caught the beer bug, discovering for the first time in his culinary career the possibilities of Belgium’s beer traditions. Nearing a decade as head chef of the restaurant, Verbeken realised if he wanted to marry these twin passions of beer and beercentric bistronomy, he would need total control, to choose the beers, and decide what went on the menu.

At Zarza, Verbeken had also experienced the hustle and stress of hunting, and holding onto, prized restaurant ratings from Gault Millau or a Michelin star usually reserved for the kind of haute cuisine, “posh” establishment Verbeken was not interested in opening. If there was one award he liked, then it was the more hearty, affordable little sibling of the Michelin star, the Bib Gourmand. “The likes of Michelin [stars], the Gault Millaus of this world….I always said, that doesn’t interest me,” Verbeken says.

What he hoped he would find in the pages of Knack was that the reviewers would understand what he was doing with Hop Gastrobar. Now sitting alone on a wooden bench in the park behind the restaurant, Bram Verbeken leafed through the magazine. He had poured two years of his life into making his vision a reality. What he cared about was that people would get it. It was a lot to hang on a restaurant review.

Bram Verbeken is a blow-in to Leuven. He grew up in Kalken, an agricultural hamlet outside Ghent. Restaurants were not a feature of his childhood, but food was. “We didn’t visit restaurants much when I was a kid,” Verbeken says, speaking through a facemask and surrounded by empty vegetable boxes in Hop Gastrobar’s dining room. But Verbeken’s father worked at then-Belgian national airline Sabena by day, and in his free time tended to his domestic menagerie—fruit and veg, chickens, a cow, lambs, and the occasional turkey.

Young Bram Verbeken pitched in to help plant seeds, pull up weeds, and feed the animals, enjoying spending time outdoors. There was a dairy farm across the road, and when he was a little older Verbeken would spend Saturdays driving tractors and helping out with the cows. His early food education, Verbeken says, was not gastronomic but homespun, his mother making simple and traditional family dinners from their farm produce. “I never knew it any other way,” he says. “If you have a cow, you have to eat everything. It’s not like you only can have entrecôte or a nice piece of filet every day….That was really inspiring.”

These formative experiences led Verbeken to enroll at the Spermalie hospitality school in Bruges, where he trained as a chef and met his future wife—chocolatier Katleen Vanderlinden. After graduating in the early 2000s, cheffing jobs followed in restaurants outside Ghent before Verbeken and Vanderlinden moved from East Flanders to Leuven’s hinterland. Having bought a house outside the city, he needed a new job. And in Leuven, there were plenty of restaurants to choose from.

The culinary world Verbeken was attempting to crack was as robust—and as conventional—as you might expect from a middle-class city that rotates to the gravitational pull of its ancient university. If you follow the route Verbeken took from Hop Gastrobar to the newsagents on that May morning of 2018, and keep going down the Mechelsestraat, eventually you’ll arrive at the Vismarkt, a former fish market and Leuven’s oldest square. It remains connected to its gastronomic past, the neighbouring streets dense with restaurants, cafés, and food shops. In this corner of Leuven, next to the city’s Oude Markt, is a fishmonger’s, a nationally-famous butcher’s (Rondou), a smattering of chicken shops, cake shops, and cafés, and the kitchen studio where Leuven’s most famous chef, Jeroen Meus, records his popular cooking show Dagelijkse Kost.

On the other side of the Vismarkt, passersby can catch the unmistakable animal whiff of fermenting milk in their nostrils. The culprit is Elsen Kaasambacht, an artisanal cheesemonger’s founded in 1995 by Fried Elsen. A bright yellow label on the shop window declares Elsen Kaasambacht to be an “Erkende Kaasrijper”, or recognised cheese ripener, recognition of their work ageing and maturing cheeses in vaulted underground cellars. Active in Leuven’s culinary scene for over 30 years, the Elsen family have supplied many of the city’s restaurants over the years—including Zarza, where Verbeken first secured gainful employment. Brothers Reinout and Willem-Jan Elsen took over their father’s business in 2020, and stated the city’s culinary principles Verbeken was about to discover: high standard food, and uncompromising quality.

For a long time, the Elsen brothers say, Leuven’s food scene was centred around the Muntstraat, on the other side of the Oude Markt and gothic town hall. This 200 metre-long street is still home to sushi restaurants, burger places, Indians, pizzerias, and so on, but restaurants have also spread out in a disorganised mass to the surrounding streets, and it was at one of these that Verbeken started work as a member of the kitchen team of Zarza in October 2008. Zarza would be the making of Verbeken as a chef, exposing him to the potential of Belgian terroir and the country’s rich beer culture, and ultimately demonstrating to him the limits to fulfilling potential if he was not in charge.

Back in his early days at Zarza—before graduating to the position of head chef, and before he had children—Verbeken spent time (too much, he says), in cafés around town, where his tastes rarely strayed too far from a gewoon pintje, he says. But gradually his tastes expanded, as he’d trek out to a nearby beer warehouse to explore what local beers they sold. Verbeken discovered streekbieren, or regional beers, like Jandrain-Jandrenouille’s IV Saison, and the trips sparked a passionate love affair with the complex acidity of Belgium’s spontaneously fermented Lambic and Geuze beers which remains undimmed in him to this day.

Verbeken wasn’t the only one waking up to what the region’s brewers were doing. The provincial government of Flemish Brabant saw the potential for beer tourism in Leuven and the surrounding area, and were keen to promote it however they could. Alongside the annual Zythos beer festival—Belgium’s largest—a competition was organised in spring 2009 to find the best bierkok or beer chef in Flemish Brabant.

The organisers of the bierkok competition were looking for a chef that would cook an “innovative and modern dish, with beer as the main ingredient”. Starter, main, dessert, it didn’t matter—so long as the beer the chefs used came from the region. Verbeken hadn’t cooked much with beer up to this point, but they had experimented with it a little, and the competition’s “no stoofvlees” rule suggested they might be open to the more forward-thinking cooking for which Zarza was known.

So he got working on a dish and pairing he thought might stand a chance of winning. He didn’t realise it at the time, but he was forming an approach that would shape his attitude to cooking for the next decade: more assertive beer flavours combined with a deceptively simple interpretation of Belgian kitchen standards. In late May 2009, Verbeken and his competition rivals descended on the Xaverius culinary centre in the nearby city of Diest.

Verbeken’s entry, a tart cherry Kriek from Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen in the Zenne valley, alongside a terrine of black pudding and apples, was “more traditional” than what he might ordinarily have cooked at Zarza, Verbeken says. But tradition was popular with the judges, and Verbeken went from a limited experience of cooking with beer to being crowned the province’s best beer chef.

Now boasting an award-winning chef, Zarza’s owner was keen to exploit his bierkok, and Verbeken mined the rich seam of creativity he had discovered during the competition to put together a beer and food menu for the restaurant. Together with his fellow chefs, he embarked on an adventure of trial and error. Sometimes the Zarza team started with an ingredient and worked towards finding a beer. Other times, they took a beer and found the food in their pantry that might work alongside it.

Slowly the team’s cooking garnered Zarza a reputation as a destination that took beer seriously. But there was something nagging away at Verbeken. The glow of being the province’s best beer chef had faded in the five years after the competition, and he chafed against the lack of control he had over the menu. He wasn’t unhappy at Zarza—quite the opposite, he says. But a spark of creativity had flared up within him.

Verbeken realised the only way he could truly express his vision of what a restaurant should be, was if he opened one himself. One that combined the deep appreciation for Belgian terroir he learned growing up, and his exploration of the creative intermarriage between food and Belgium’s rich brewing tradition. “A new kind of restaurant,” he says. That Leuven was going to be the location was clear. What was less clear was whether Leuven was ready for it.

On the other side of Hop Gastrobar’s canalside location on Leuven’s Vaartkom, separated by several lanes of highway, is the massive, groundscraping, modern Stella Artois brewery, responsible for the blanket of sweet malty fumes that cover the city on brew days. But despite hosting the headquarters of the world’s largest brewery, Leuven isn’t really a beer town.

It’s proud of its brewing heritage, but when it comes to the city’s psyche and self-identity, it’s another institution which dominates: the ubiquitous Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. The city only recently acquired an independent craft beer-focused bottleshop, and in 2020 Leuven’s first microbrewery opened in a suburb by the train station. Restaurants that took serious beer seriously, like Zarza, and producers keen to explore the possibilities of beer and food, like the Elsen brothers, were the exception rather than the rule.

For all that Belgium styles itself as the beer country, its chefs have been largely resistant to beer’s charms. Just ask beer sommelier and writer Sofie Vanrafelghem. In January 2021, Vanrafelghem fired off a tweet, venting her frustration about beer’s absence from Belgium’s just-announced coterie of Michelin stars: “…Because beer is not important in beer country Belgium, my stupid mistake.” It was just the latest frustration from a longtime advocate for beer’s rightful place alongside wine on the dinner table. “We’re a beer country, not a wine country,” she says.

Vanrafelghem’s issues are manifold. Chefs are not trained in culinary school about beer as they are with wine. Vanrafelghem thinks the typical Belgian diner is conservative in their dining and drinking tastes. Consumption figures suggest they stick to wine: in 2017, Belgium consumed three million hectolitres of the stuff. “It’s a habit that’s difficult to crack,” Vanrafelghem says—for restaurant sommeliers and drinkers alike. And then there’s the thorny issue of the meagre profit margins associated with beer. “You can make money with beer. It’s bullshit that you can’t…” she says. “You just can’t expect to make much money if all you’re serving is Pils and Duvel; you need something more interesting.”

Chefs in Belgium who take beer seriously—and in turn whose cooking is taken seriously by the wider culinary world—are in short supply. There were pioneers like TV chef Guy Van Cauteren, awarded two Michelin stars for his cooking at ’t Laurierblad in Berlare and with whom Verbeken had completed an internship during his studies. There was Alain Fayt and Dirk Myny at Restobieres and Les Brigittines respectively, both in Brussels, though the former’s cooking perhaps leaned too traditionalist for Zarza. And Stefaan Couttenye in the West-Flemish village of Watou, cooking with beer at his restaurant ‘t Hommelhof since the early 1980s.

But beyond these few, it was the rare chef that was centring his restaurant so visibly around beer as Verbeken would do with Hop Gastrobar. As loudly as Vanrafelghem would advocate and as much as these pioneers might excite, the wider dining public seemed happy to stick with a bottle of red or white. “The only way it’s gonna change is when consumers are asking more for beer,” says Vanrafelghem. “That’s the only way it’s gonna change.”

If selling his prospective customers on beer was one challenge he was grappling with, Verbeken also worried locals might not get the concept of a “gastrobar”. Would people be okay with a fixed menu? Would they be willing to step outside of the brasserie paradigm of sturdy Flemish cooking for something more ambitious?

“I never wanted a posh restaurant,” Verbeken says. “But I also didn’t want to do like a classic brasserie kaart. I had to do something creative, and be able to change whenever I like.” He landed somewhere in-between: bistronomy. Verbeken didn’t invent bistronomy—a portmanteau of bistro and gastronomy—but it was reasonably new to Leuven. In bistronomy, says Verbeken, a restaurant is where “everything is a little bit more down to earth.” It’s the kind of place where you’d be just as welcome if you showed up with a reservation in a formal suit and tie, as you would if you dropped in for an impromptu lunch on the terrace in shorts and flip flops.

Verbeken kitted the restaurant out with an open-facing kitchen, so he could interact more easily with customers, and so they in turn could see how their food was being put together. Diners could sit on raised stools at a bar opposite the kitchen, or on warm-coloured, bare wooden tables by the floor-to-ceiling windows looking out onto the boats in the canal. “It has to be cosy….full of people, lots of candles, the music just loud enough,” he adds. “But at the same time, we have to have a real restaurant experience towards food and drinks.”

Verbeken’s hope was that once he got people into Hop Gastrobar, he could cajole them into ordering the kinds of beers he wanted to showcase in his “new kind of restaurant”. He planned to stack the menu with beers from Belgium’s new wave independent brewers—‘t Verzet, De la Senne, De Ranke, and beers like the IV Saison from Jandrain-Jandrenouille. He drew on his love for Lambic and Oude Geuze, and his knowledge of other wild fermentation breweries in Germany and The Netherlands. He also made sure to have a reliable Duvel on hand for less adventurous diners.

But the beer was going to be only one half of the equation. Alongside beer, Hop Gastrobar was going to showcase the best of Belgian terroir, interpreting ingredients grown or reared in Belgium with creativity and respect. If adventurous diners made it to the Vaartkom, and found beer that surprised them, what would they think of Verbeken’s bistronomic exploration of Belgian standards?

Take his interpretation of Belgian staple moules frites, on the menu in the first months of 2018. “What we were showing off was what we wanted to do,” Verbeken says. “Have a Belgian traditional dish, but we’re going to make something different [out] of it.” Instead of a tub of mussels cooked in Geuze alongside a basket of fresh fries, Verbeken made a purée from the leftover vegetables steamed with the mussels, dried them, and shaped them into fries that were “full of mussel flavour.”

One of the restaurant’s early desserts—a confection of hazelnut praline, bergamot, and pear cooked with (and named after) Dark Sister Black IPA from Brussels Beer Project—showed what Verbeken and his new team could do with beer in dishes. He also adapted his cooking with beer to accommodate the dietary needs of coeliac customers.

Beer bistronomy came with constraints. His menu would be seasonal—food and beer. It would be affordable, the profit margins modest. But this was a challenge his experiments at Zarza had prepared him for. One four-course menu featured beetroot with smoked haddock and horseradish, wild duck with celery, parsley, pear and muscat, and a dessert of blackberries with almond, lemon, and verbena.

Verbeken lent on his youthful farming experiences, bringing along with him whatever edible herbs he had plucked from the permaculture vegetable garden at the back of his house. He even shoehorned in some produce from his father’s vegetable patch, including peas he says he can’t find better anywhere else. Bistronomic cooking was a creative choice for Verbeken, but also a logical one. “There are beautiful products all over the world,” he says. “[But] I really like to put Belgian produce in the spotlight. Because people sometimes forget about it.”

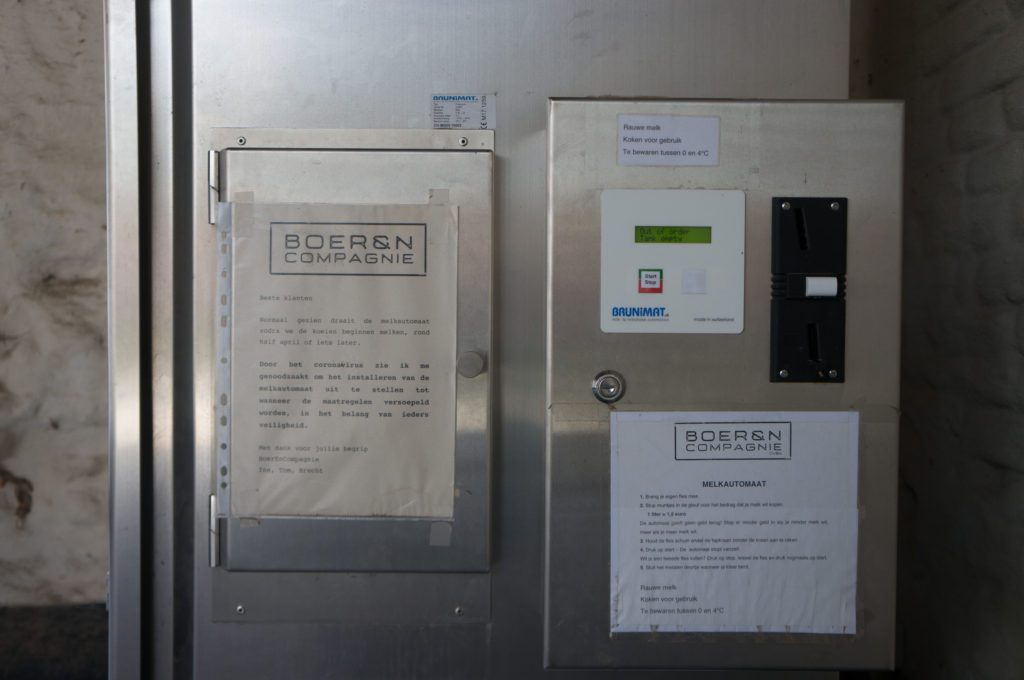

In Leuven, Verbeken is enthusiastic about BoerEnCompagnie, a small farm based at the city’s Abdij van Park Abbey whose fresh cheeses he has brought into Hop Gastrobar’s kitchen. There is a common thread shared by Verbeken’s suppliers—they are keeping old traditions alive, and reviving dying ones. Verbeken’s curiosity and his interest in new producers doesn’t stop at food, and nor do his site visits. He says he’s visited almost every brewery on his menu, and it was on one such jaunt that he met former philosophy teacher-turned self-sufficient farmer and brewer Tom Jacobs.

Jacobs lives on the outskirts of the town of Kortenaken, in Flemish apple-growing country. Since 2018, together with his brother Wim, Jacobs has been making beer, wine, cider, and a blend of all three on his farm under their Antidoot Wilde Fermenten label. When Antidoot launched, Jacobs didn’t expect to sell much into restaurants. Then Verbeken showed up at the farm one sunny afternoon. The Jacobs brothers didn’t even have any Antidoot beers ready for sale, so together they drank some cider and talked about Antidoot’s plans for the future.

Verbeken recognised a kindred spirit in Tom Jacobs, and they have continued to work closely. Hop Gastrobar has since become a regular haunt for the brewery’s cultish fanbase. Antidoot is just one among several of a new generation of brewers about whom Verbeken is hugely enthusiastic, believing they are producing a range and complexity of beers that make his job easier as a chef looking for added-value beer pairings.

It’s a mutual appreciation society. 3 Fonteinen, whose Kriek Verbeken used in his competition-winning dish back in 2009, recognise what he’s doing to push forward the gastronomic appreciation of Belgian beer. “In Belgium, a lot of restaurants have done their homework on the wine list….but they can still work a lot on what the beer should be about,” says Werner Van Obberghen of 3 Fonteinen, echoing the experiences of Sofie Vanrafelghem. “And I think Hop [Gastrobar] in Leuven is a very nice example of how it should be done. They have not only a very elaborate beer list, but they also go with the pairings. And for us, that’s the reason why we love to work with them.”

Verbeken had a clarity of vision which he believed diners could engage with at the tables of Hop Gastrobar. Now he just needed to get those customers to the restaurant in the first place.

Hop Gastrobar is located on the groundfloor of a redbrick newbuild at the end of the Vaartkom, the harbour where the Leuven-Mechelen canal terminates, and which for decades was dominated by the Stella Artois brewery and its massive grain silos. Sitting on the water, squeezed between new housing developments and the city’s ring road, Verbeken’s “little piece of Leuven,” as he calls it, is far (in relative terms) from Leuven’s inner city restaurant quarter. What’s more, the neighbourhood was—and remains—in the throes of redevelopment. Towering yellow cranes crowd the skyline, busy knocking down what remains of Stella’s 20th century brewery and maltings, and erecting in its place gleaming, modern apartment complexes.

In Verbeken’s time in Leuven, there had been a slow drip of new restaurant projects away from the Muntstraat and towards this part of town, but it didn’t always work out. Jeroen Meus, Leuven’s most famous chef and himself recognised at one time as a “Beer & Gastronomy Ambassador”, opened his Luzine restaurant further along the canal in an old jam factory in 2005. By 2014 Meus had departed, and a year later the business was declared bankrupt.

Verbeken hoped that Hop Gastrobar’s more overt connection with the area’s beer history might play in his favour—the old, crumbling cylindrical Artois grain stores glower at the restaurant from across the canal.

The neighbourhood has moved on since the early 2010s. From their cheesemonger outpost on the Mechelsestraat, the Elsen brothers have seen a slow leakage of restaurants away from Leuven’s expensive inner city towards the more affordable industrial outskirts and suburban neighbourhoods.

But in the weeks after Verbeken opened Hop Gastrobar’s doors for the first time in February 2018, doubts about the location crept into his mind. The dinner service was running as he had hoped. Diners familiar with his work at Zarza were eager to see what he had accomplished in the two-year interregnum since his departure from that restaurant.

Lunch was another matter. There was little passing trade in those dark late-winter days. Verbeken’s gamble—one that took two years of his life, and his financial security—was at risk of not paying off. If Leuven’s wider culinary world didn’t grasp what he was trying to do with Hop Gastrobar, would his lunch trade eventually recover? Would he be able to sustain his dinner sittings? Did Leuven want a new kind of restaurant at all?

And so to early summer, Verbeken sitting on a bench in an empty park, flicking through his copy of Knack magazine. Verbeken has a positive temper, and was convinced Hop Gastrobar would succeed in time; but reviews in national media can play a major role in helping diners understand what a restaurant is all about. Verbeken flicked through the pages until he saw it.

The headline read: “Bistronomie with a starring role for beer”. Knack’s food critic Barbara Serulus had this to say: “Hop served what for me was a perfect lunch.” Serulus flagged a beer menu which “showcases the diversity of our Belgian beer landscape,” paired with dishes that were “light, well-balanced and made with beautiful, fresh ingredients.” Four stars. Serulus might have been copying Verbeken’s business plan for Hop Gastrobar word for word. Verbeken folded up the magazine, hopped on his bike and wheeled back to the restaurant, proud and relieved. And above all, validated. “The people get it,” he says.

The previously sluggish lunch service picked up and positive reviews and awards trickled in over the following two years. A strong score from restaurant guide Gault Millau was followed by a review in the weekend magazine of the business newspaper De Tijd that concluded: “Tasty dishes, competitive prices, and a great atmosphere; for that trio, everyone would be happy to come back…Hop is top.” It was a review that would blow the doors off the place.

“I don’t have it framed on the wall, but it was crazy,” Verbeken says. “We’ve been fully booked every lunch [and] every dinner for six months….the effect was really unbelievable.” There was also a chance to celebrate in early 2020, when Verbeken teamed up with Tom Jacobs of Antidoot for a full-on six-course dinner in a packed dining room celebrating both businesses’ second birthday.

And then the virus. COVID-19 arrived in Belgium, necessitating a shift from dine-in to take-out. The chopping and changing, the empty dining room, the lack of contact with his customers; it has sapped Verbeken’s enthusiasm. “The best way to inspire me is to just put a fridge full of food [where] I have no idea what we are going to make. And then we start like a puzzle,” he says. “That’s a little bit difficult when your restaurant is closed.”

Verbeken focussed on keeping his business afloat during the darkest hours ever experienced by Belgium’s hospitality industry. But unbeknownst to him, there were undercover agents infiltrating his restaurant. Over the course of 2020, clandestine reviewers from the Michelin guide dined at Hop Gastrobar multiple times.

On one occasion, they ate beef with horseradish, roasted shallot, and bbq celeriac; on another, farm chicken with savoy cabbage and cashew. And their visits were not in vain; in December 2020 Michelin included Hop Gastrobar in that year’s Bib Gourmand, their guide for restaurants serving “exceptionally good food at moderate prices” and judged to the same criteria as their Michelin starred restaurants.

The Michelin reviewers raised its “playful combinations paired with surprising wines or craft beers.” The review read: The chefs eschew luxury ingredients and have honed in on the flavours of yesteryear and variations of subtle textures. Gourmet dining in a delightfully casual setting that hits the spot every time!”

Verbeken never wanted a posh restaurant. He had never longed for a Michelin star. But a Bib Gourmand? That was something else entirely. The central conceit of Hop Gastrobar—quality ingredients transformed into exceptional meals in a convivial and accessible atmosphere—might have been precision-designed to meet the criteria of the Michelin Bib.

Reviews and awards matter to Verbeken only as evidence that his vision to pair the best of Belgium’s terroir, both edible and drinkable, has resonated with the people who have eaten at Hop Gastrobar, a new kind of restaurant.

*