Before Chris Vandewalle started his own brewery in Lo-Reninge, he learned about beer’s cultural power from historical brewery records. Through his house brewery—Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle—he set out to renew the region’s traditions.

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “War Chest” series. Read more.

When I enter number 43 on the Zwartestraat in Lo-Reninge, I see a brewery that has for the previous nine years blended into Chris Vandewalle’s home. In the reception area, there are framed black and white historical portraits of family members set out on chests of drawers, many of whom seem to have been involved in the local hop-picking and brewing industries. One that takes centre stage is a black and white photo of a young girl.

When I meet Vandewalle, he’s wearing the shirt and slacks he has worn earlier that day at work. Generally, he’s thoughtful about the way he dresses, often seen in a three-piece suit with waistcoat and dicky bow, glasses with edgy, modern frames. It’s the kind of formal wear worn by Lo-Reninge brewers of yesteryear, such as the former brewer of Brouwerij Het Damberd, Georges Croigny, who lived at number 1 on the Hogebrugstraat.

In the entrance hall to his house brewery, not everything is black and white. Two things of vibrant colour immediately capture my attention.

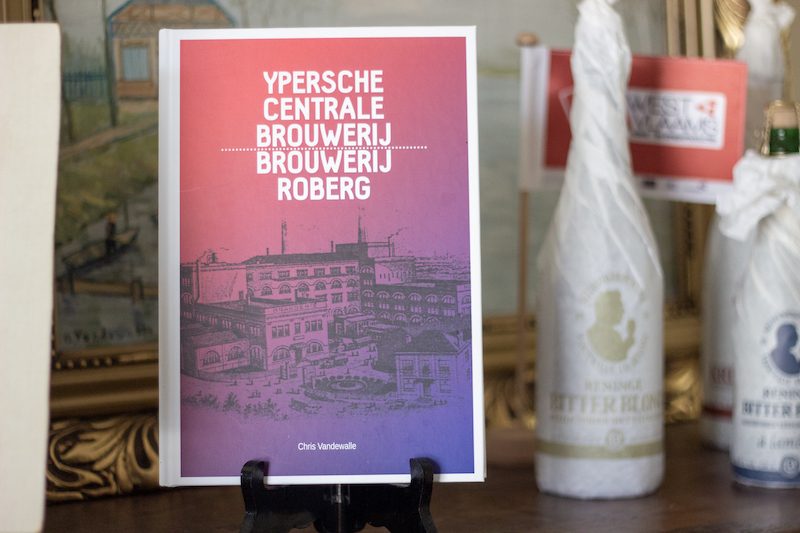

The first is a hardback book sat upright on a stand with a red and purple cover. It features a beautiful illustration of an old brewery, and is titled: “Van Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij (1921-1961) naar Brouwerij Roberg (1961-1976)”. It’s a book about a former brewery in Ieper called the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij. The author is Chris Vandewalle.

On the other side of the room is the second item of colour: a large oil-based painting of two flying birds facing each other, wings out-stretched, deep turquoise and azure blue. They look like phoenix: mythological birds in ancient greek folklore associated with the sun which were said to have obtained new life by arising from the ashes of their predecessors.

My visit to Lo-Reninge is a rescheduled one. I was supposed to meet with Chris Vandewalle two weeks previously but his grandmother passed away just as I was due to visit and Vandewalle had called to rearrange. Yvonne Decroos lived to the age of 99 years, born on 24 June 1921 in a village 10 minutes to the west of Lo-Reninge by car. On the day after her funeral, Vandewalle had posted a black and white photograph on his Instagram feed of himself and Decroos clinking a glass of beer together. “Her life seasons are now complete,” Vandewalle wrote in the caption to the photo. “Her cuisine and classic dishes are etched in our memories.”

It turns out that the young girl in the black and white photograph that I had noticed in the reception area is his grandmother and he begins to reminisce about his chats with her over the years. Yvonne Decroos taught him that food was seasonal, and that everything in nature was connected and in balance. He tells me how she turned the fresh fruit she sourced at farms into jams, locally grown vegetables into oven dishes, milk from the neighbour’s cows into cheese, and how she sourced honey from bee-keepers she knew in the area. He tells me they talked about the cafés she frequented in her youth and the beers that were produced when hop harvests allowed. “She was my living link to history,” he says.

Vandewalle lives and breathes history. He works four days a week as an archivist for the city of Diksmuide, a job he has had since 1998 which entails assessing, collecting, organising, and preserving historical records which are determined to have long-term value for the region. But history is only alive when it provides context for contemporary living and Vandewalle felt there was something missing in his life. Through his work, he regularly came across family records, personal affairs, brewing logs, and company documents, which demonstrated the importance of beer to social life and hinted at a fascinating beer culture in years gone by. He also discovered that previous generations of his family—most of whom were in some way connected to his grandmother Yvonne Decroos—had been involved in important breweries throughout the region. The discoveries sparked an obsession with resurrecting the beer and the brewing traditions of the Westhoek.

Before he opened his brewery in 2011, it was difficult to find people with whom he could share his newfound interest in beer. He had never brewed before and knew nobody in the beer industry in Belgium. His parents and sister had no interest in beer, focusing all their time and energy into a fine meats business in which they sold cured hams and pâtes. Those in his professional network of archivists did not associate historical brewing with modern beer in the same way as Vandewalle. And he didn’t have a partner with whom he could share his hopes and dreams to perhaps one day brew beer inspired by historical brewing traditions.

Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle, next year 10 years in existence, was borne from Vandewalle’s obsession for local history and a passion for regional food and drink. But in the reflections on his relationship with his grandmother; in the trawling through historical brewery archives; and in the search for someone with whom he can share these passions, there’s a deeper personal quest. It feels like Chris Vandewalle is trying to work out whether he should continue focussing on the black and white, or whether he should be living in colour.

On my drive here, I notice that Lo-Reninge is actually made up of several different villages: Lo and Reninge, but also Noordschote and Pollinkhove. Around 3,300 people live across the four villages, which lie between the cities of Ieper and Veurne in Belgium’s northwestern corner. Immaculately engineered canals cross flat rich agricultural land, interrupted only by quaint village churches and peaceful cobbled squares, many dating back to the Middle Ages.

It’s a series of villages which was greatly affected by World War I. “Gapaardhoek” in Lo-Reninge—known locally as the “Camp des Américains”—is the site of an old barracks and field kitchen built in 1917 where military units could temporarily leave trench warfare for periods of respite.

It’s also a community which was once rich in breweries. The former “Grey Sisters” nunnery started brewing in 1655 but is now an administrative centre. The building in which the St. Jozef brewery operated until 1962 is now a protected monument. At one time, Lo-Reninge was home to breweries such as Het Damberd, Pillaert, Oud Wethuis, St. Louis, La Fourche, Grimmelprez, and Delefortrie, all of whom brewed beer almost exclusively for people in Lo, Reninge, Noordschote, and Pollinhove. Today, because of the challenges of surviving both World Wars in the Westhoek and the commercial dominance of large global brewing conglomerates, Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle is the only brewery in existence in Lo-Reninge.

In 2010, a year before he opened his brewery, Vandewalle met Karel Dendauw, a tall, bearded, resident of Lendelede with a disarming smile and softly-spoken manner. Dendauw worked in design for a company which specialised in the production of bespoke concrete steps. Vandewalle and Dendauw started dating, sharing a connection that made the regular 50 kilometre commutes from Lo-Reninge to Lendelede to see each other easier to take. They also shared a creative spirit: Dendauw harboured ambitions to paint, and Vandewalle encouraged Dendauw to follow his dream of becoming an artist. He also tried to get Dendauw excited about beer. “He was just drinking Lager beers from industrial breweries,” says Vandewalle. Converting him would take some time.

When Vandewalle moved into his house in Lo-Reninge that same year, he was in the process of recording the oral history of groups of local people as part of a project for the city of Diksmuide for his job as an archivist. Some of the interviewees were older brewers who had worked producing beer in the surrounding villages. He discovered old brewing logs and interesting historical brewing documents and he realised he couldn’t decipher them without understanding the technical elements of brewing. He signed up for a brewing course in Ghent. “I wanted to feel it in my fingers,” he says.

Vandewalle shows me an old brewing log from 1872. The pages are flimsy and he handles the book with extreme care, showing me how recipes were constructed. It’s been by trawling through documents such as these that Vandewalle discovered his grandmother Yvonne Decroos was related back up her family tree to a brewer called Petrus Franciscus Van Eecke, who in the late 1700s married brewer’s daughter Johanna Theresia De Mey, developing the St-Juliaan brewery together in Langemark.

Another connection to brewing he found in Decroos’ bloodline—and his own—was in the form of Catharina Constantia Van der Heyden-Markey from Westveleteren, who bought “Den Bourgondischen Schild” brewery in Pollinkhove in 1822, sparking three generations of family involvement until the First World War. The first line on the website of Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle reads: “We are a young brewing company, but we boast a family brewing tradition with roots as far back as the 18th century.”

An important historical brewing connection in his family which could be attributed to Yvonne Decroos and her Van Eecke blood was to the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij, located for 55 years behind the train station on the Chaussée de Dickebusch in Ieper. It’s the brewery about which he has written the book on display in his entrance hall, a beautifully designed 198 page hardback containing rich archival material: images showing the evolution of the brewery; old labels, glassware, and beer mats relating to the beers produced there; architectural plans of the buildings used; the family trees of those involved; copies of old letters; and photography of street festivals, dinners, and events, which shine a light on the cultural impact of the brewery’s beer on the people of the Westhoek.

Middle: A horse and cart driver distributes beers of the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij. Photo Credit © Westhoek Verbeeldt.

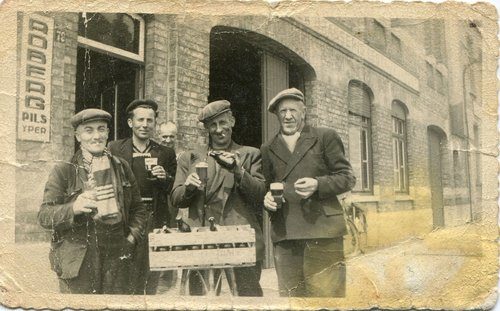

Right: Beer drinkers enjoying Roberg Pils at Café Central, one of the properties owned by Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij. Photo Credit © Westhoek Verbeeldt

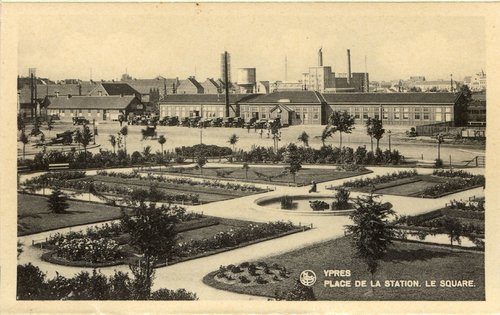

The Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij was set up in 1921, just after the First World War when the local population in the Westhoek claimed government subsidies to rebuild the houses, shops, schools, and churches that were destroyed during the war, and to renew the drainage, sewers, and water systems that had been rendered unusable. Several families from Ieper, Boezinge, Kemmel, Langemark, Poperinge and Westouter—who all owned separate breweries before the First World War—pooled their resources together to establish one mega cooperative brewery they would call the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij which they believed would put the Westhoek on the map.

In 2017, Vandewalle launched his book about the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij at the Hop Museum in Poperinge to around one hundred attendees, including the Councillor for Culture of Poperinge, the Councillor for Ieper’s Archive, the Curator of the Hop Museum, hop farmers like Joris Cambie of De Plukker, brewers such as Philippe Leroy of Brouwerij Leroy, a range of beer media, the board of the local beer tasting club, and even the last Director of the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij, Filip Donk.

Wearing a brown suit, blue shirt, tan-coloured belt, and striped dicky-bow, he explained to attendees that the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij was a show of regional force. Each family brought to the table their distribution network of cafés, providing financial and market muscle that would give the Westhoek a name nationally. “When you are bigger and stronger, you have to say something,” he says, sticking out his chest to demonstrate the might of the new enterprise.

Despite its comprehensive construction and engaging narrative, Vandewalle’s book remains a niche historical resource. The City Archive of Ieper who published the book printed only 400 copies. “Maybe my books are boring to read,” says Vandewalle. “I don’t know. But for me it’s very important to keep the whole history in that book. You have the interviews with the brewery and the research in the local documents. It’s deep-grounded research. It’s not a commercial version of brewery history.” Brewery history—despite its cultural importance—is a tough sell amongst enthusiasts who care only about the next beer and the next brewery.

What attracted Vandewalle to the story of the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij was that of a younger generation trying to take the old and make something new, establishing a different way of working, brewing Lagers on a larger scale rather than mixed fermentation beers, and in cooperation with other families rather than alone. Many believed it was because they had each been financially crippled by the First World War but Vandewalle explained to me that this was not the case. Because of their slightly further distance from the front line of battle, these small family breweries in the Westhoek—those to the west of the Ijzer river—brewed all the way through the war and in many cases, enjoyed huge commercial success.

Thousands of soldiers on the front line demanded beer on leave from trench duties and locals needed beer to maintain some sense of normality throughout the conflict. It was not a story of desperation or necessity. The story of the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij was one of confidence, hope, and renewal.

Vandewalle leads me out the back of his kitchen, through a small garden into an outhouse where he brews every Friday on a Speidel Braumeister and a Polsonelli kettle. He transfers two batches of 500L into a converted milk tank where it undergoes an open fermentation. The brew finishes at six in the evening, and he pitches his yeast into cooled wort at around 9pm. Once fermentation is complete, he transfers the beer into plastic containers, which are placed in the fridge for conditioning, and later for blending, priming, and packaging.

In naming the brewery Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle, he has placed at the centre of his activities the seasonal aspect of food production about which his grandmother taught him, and in this way it feels like her memory will be forever preserved as long as he can continue to produce bottles of his beer. His set-up is rudimentary but his commitment to respect the spirit of this seasonality is absolute. In September, October, and November, he brews his Reninge Bitter Blond, using only fresh hops from the Autumn hop harvest in nearby Poperinge. During the winter, he produces wort for his Oud Bruin. In the spring and summer, he works on his cherry beer. His grandmother had taught him that as nature evolves across the seasons, everything and everyone has its own time and place.

We head to a room in which Vandewalle has accumulated oak barrels for the aging of his Oud Bruin, a mixed fermentation beer with a sour and sweet flavour profile. It’s brewed in the winter, matured in barrels or foeders which impart flavours from the oak and facilitate oxidation at a slower pace, allowing the barrels to breath air which feeds lactic acid bacteria. Vandewalle sourced his barrels from a nearby winery in Heuvelland—”Entre-Deux-Monts”, meaning “Between Two Mountains”—and has since bought Burgundy and Bordeaux barrels on trips to France.

Photo Credit © Westhoek Verbeeldt.

In the same barrels, Vandewalle produces the Reninge Krieken Rood, a mixed fermentation cherry beer with subtle notes of almond, wet leaves, and oak. In historical documents he found during his work as an archivist, he discovered that the former Rouzee and Criem breweries of Lo-Reninge produced beers with cherries grown in Veurne, the city where he had been born. To give this beer a rebirth, he travels once a year to a fruit farm in Veurne called De Vloo where he collects the cherries. He adds 45kgs of the fruit to each barrel of 220L of Oud Bruin, allowing them to sit on the beer from the time of the summer harvest to blending time the following spring.

We walk through Vandewalle’s small garden, where lavender plants abound and where two bee hives sit side by side in a corner. Vandewalle explains that he takes part in a conservation project which aims to address dwindling bee populations and reduced pollination for agricultural lands and orchards. He jokes that he needs the bees to pollinate for cherry cultivation and that he now has thirty thousand employees in his brewery.

It’s a recurring theme: the leftover cherries are used to produce an “eau de vie” by a distiller friend. His spent grain is delivered to a local farmer who he says “has a very special variety of pigs”. Another friend, he says, used to come and take some grains to make bread. The bees, and the cherries, and the grain, and the bread. They all hint at an extension of his philosophy of balance, nature, and seasonal renewal. The old makes way for the new. “If I get things from nature, I will give things back,” says Vandewalle. “It’s a whole ecosystem. I learned that from my grandmother.”

Photo Credit © Westhoek Verbeeldt

Vandewalle’s mixed fermentation beer—the Reninge Oud Bruin—was inspired by Brouwerij Het Damberd, one of Lo-Reninge’s most famous former breweries. Het Damberd was located next to Lo’s famous “Caesar’s tree”, a yew tree to which Julius Caesar is said to have tied his horse. Het Damberd’s Georges Croigny was known throughout the villages for winning a medal for his Damberd Oud Bruin at a prestigious competition in Oostende in 1907. Vandewalle felt in awe of that victory, and nervous about how his brewery and its beers might be perceived. “I’m always a little scared about what people are thinking about me,” he says. He dreamed of one day emulating Georges Croigny in winning a medal for his Oud Bruin and becoming the pride of Lo-Reninge.

After showing me around the brewery, Vandewalle takes me back to his living room. There are no chairs or sofas, no TV or radio. Just a few pieces of art: panels of religious iconography beside a long, low-set rectangular window, and one impressionist landscape painting.

On the part of the tiled floor space not taken up by the bottling machine are hundreds of filled green champagne bottles containing beer refermenting with the help of the living room radiators, untouched for several weeks as Vandewalle lives his life around them. The bottles strewn out across the floor are labelless, identical except for their crown corks: golden for the Reninge Bitter Blond, silver for the Reninge Oud Bruin, white for the Reninge Bitter Blond à Lambiek; and red for the Reninge Krieken Rood. Each bottle will not be labelled, but individually encased in paper wrapping, by hand, similar to the old packaging of the Liefmans brewery in Oudenaarde. “It’s something they used to do in this region too,” says Vandewalle.

Before he bought the bottling machine, he would fill bottles by hand, one by one, alone, maxing out at 200 per day. It was a schedule which required multiple days to bottle one batch of beer. It was tedious work, requiring long hours, and physically demanding. Vandewalle tells me that he would have held a bottle seven different times in his hand as he rinsed it, filled it, corked it, caged it, cleaned it, wrapped it, and put it in boxes. It was a situation that needed to change. Vandewalle decided to ask to help.

Chris Vandewalle’s father had no experience working with beer, but as a charcutier, working for decades making fine meats and pâtes, he understood food production and quality control. He was also a practical man, having worked with machinery throughout his life. Having seen how much time and effort his son had put into the brewery, he wanted to see Chris Vandewalle be recognised for his beers.

Chris Vandewalle and his father began discussing the technical specifications of what they required and what they could afford within their budget. They decided to buy a KTM Troxler bottle filling and capping system from Germany, one which would allow them to bottle larger amounts at a time, 2,000 bottles per day instead of 200, combining different batches of the same beer, and facilitating package in two different types of bottle. The machine would also improve quality, minimising oxygen pick-up by counter-filling with CO2 and capping on foam. In 2016, Vandewalle’s beer would be packaged much quicker and it would be of a higher quality in the bottle. Maybe if they entered it into a beer competition, it had a chance of winning an award.

At the time, Karel Dendauw, now Vandewalle’s life partner, was developing a taste for Vandewalle’s beers and began accompanying him to events to represent the brewery. He even appeared on behalf of the brewery in a photo with Vandewalle on page 29 of a brochure promoting Lo-Reninge as a tourist destination, a feature where Vandewalle’s beers were paired with several dishes at De Hooipiete restaurant in Lo-Reninge. “You grow together in the concept,” says Vandewalle. “He enjoys drinking a very good beer and that’s one of the things to be proud of. You can learn to drink.”

Despite having no interest in the project a few years previously, Karel Dendauw and Vandewalle’s parents became regular volunteers at Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle. “My parents were very silent when I started the brewery,” says Vandewalle. “But now they are very proud.” Dendauw would load empty bottles and Vandewalle’s father would unload filled bottles while Chris Vandewalle checked fill levels and capping or corking. Vandewalle’s mother would wrap every bottle by hand with special paper, stamping each one individually with the date. It’s the type of work that requires people to work closely together, and to care about what they are doing.

When we return to the entrance hall at the end of our tour of the house brewery, wondering whether there has been any recognition of this work, I see framed certificates hanging on the wall.

On 7 February 2017, with the new bottling machine operational, Vandewalle attended the Beer Awards, a competition where consumers vote online for their favourite Belgian beers across a variety of categories. In a packed room of brewers at Jilles Beer & Burger restaurant in Bruges, the results of the beer category “Spontaneous and Mixed, Dark” were called. ’t Verzet Oud Bruin took the bronze. Liefmans Goudenband took silver. The winner of the gold medal was Reninge Oud Bruin from Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle. Chris Vandewalle walked through a room full of brewers to cheers and large applause and collected his award, dressed in a pink shirt and a brown highland tweed three-piece suit.

Several media outlets were present and wanted to interview Vandewalle about the beers. He explained that he knew from his research in archives that Oud Bruin and Kriek had once been popular in the Westhoek and he told the story of Georges Croigny winning a medal for his Damberd Oud Bruin in 1907. The following week, there was an article about Vandewalle’s victory in one of the Flemish online papers. The headline read: “Oud Bruin beer wins gold again after 110 years”.

In Kantien in Ghent the following year, on 8 February 2018, Vandewalle once again attended the Beer Awards, this time wearing a dark suit and waistcoat with a black and white spotted tie. Reninge Oud Bruin took gold in the “Spontaneous and Mixed, Dark” category again, beating out Liefmans Goudenband and Slaapmutske Flemish Old Style Sour. But he was called up a second time in 2018, with his cherry beer Reninge Krieken Rood winning the Fruit beer category, ahead of Tilquin Oude Pinot Noir and Cuvée Soeur’Ise. The newspapers sang his praise again, including the local edition of Het Laatste Nieuws. Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle was the pride of Lo-Reninge.

At the end of our tour in his house, Chris Vandewalle opens a bottle of Reninge Oud Bruin to share with me, and then produces a cheese that he’d like me to try. It’s one he has made himself from cow’s milk that has come from the farm of Karel Dendauw’s brother. The cheese is creamy with the light, fresh nature of a young cheese made from cow’s milk. “It’s the first time I make cheese,” Vandewalle says, proudly. “It needs some time.”

Vandewalle pours the Oud Bruin slowly, foam filling more than half the glass. His dicky-bow is off and the top button of his shirt is undone. He launches into a story about his grandmother again, telling me about the cheeses, and the jams, and the honeys that Yvonne Decroos used to make. He tells me about how after her funeral the previous week, all of her grandchildren gathered in the kitchen of her home to talk about what they would be eating and drinking together. “She created her own things,” he says in between sips of beer and nibbles of cheese. “That’s the identity of the people here.”

Just before I’m about to leave the house brewery in Lo-Reninge, Karel Dendauw video calls Vandewalle and I’m able to say hello through the screen of a mobile phone. Vandewalle mentions to Dendauw that I had been interested in the entrance-hall painting, two colourful birds that look like phoenix, wings spread, facing each other in a meeting of dramatic energy. It turns out that the painting is a work by Dendauw. It had been noticed by local art organisations and Dendauw had been invited to take part in the “2020 Kunstzomer”, a summer art exhibition of 40 contemporary artists across five cities and municipalities in the Leie valley between June and September 2020.

Being a symbol of the new arising out of the old, the phoenix has been chosen for the Westhoek’s “Fenix 2020” project to highlight the rebuilding of the area after the First World War. There are similar themes in the story of the Ypersche Centrale Brouwerij, a cooperation of families in the Westhoek which sought to renew and transform the fate of the region after the War, in which a generation of brewers changed the direction of their lives by focussing on the now.

But it might also extend to personal transformations: Chris Vandewalle is evolving not only as a published archivist, but as an award-winning brewer. Vandewalle’s parents have gone from focussing on their own food business to sharing the deepest passion of their only son. In addition to designing concrete stairs, Karel Dendauw is at long last an exhibiting artist. On the video call, I ask Dendauw what his bird painting means. “It’s about freedom,” he says quietly. “It’s about finding yourself.”

When I return home from my trip to Lo-Reninge, I visit the website of Seizoensbrouwerij Vandewalle to check out the information he has posted there on each of his beers. There’s a short promotional video for the brewery which shows viewers the oak barrels and bottling line.

At the end of the video, Vandewalle can be seen serving his beer during a picnic to a small group of people, blankets spread out on the flat, peaceful fields around Lo-Reninge which seem so far removed from the action that took place there during the First World War. I recognise Vandewalle’s parents in the video from photos in his house, as they slice cured meats and cheese to serve with the beers. I see Karel Dendauw there too, in a crisp white shirt and navy slacks, dunking a bucket into the Ijzer river with Vandewalle’s father, the pair fetching water to keep the beer cold.

It’s a brewery’s promotional video, but it’s also a technicolour scene of a family who are present and living in the now, laughing and chatting and eating and clinking glasses together, not an archive or historical book in sight, the spirit of Yvonne Decroos alive in every bite and drink.

*