Through his Lambic blendery Het Boerenerf, Senne Eylenbosch saved his father’s farm, discovered his own identity, and began the next chapter in his family’s storied Lambic heritage.

Words by Breandán Kearney

Photography by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Oisín Kearney and Eoghan Walsh

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “New Arrivals” series.

I.

Mandibles

If you visit his farm on the Sollenberg hill around sunset, during a particular window of three weeks starting in mid-June, you’ll find Senne Eylenbosch outside. There, in the Senne Valley village of Huizingen, as the midsummer light dims and the temperature drops, Eylenbosch will be poking around the trees, hedgerows, and logs scattered across his land, searching intently for an insect. “It’s like, some people go fishing,” he says. “I go searching for stag beetles.”

Stag beetles are the largest territorial insect in Europe, known for their oversized mandibles—the jaw-like appendages near their mouth that resemble deer antlers and that are used to grasp, crush, or cut their food. When Eylenbosch finds stag beetles, he measures them and counts how many teeth their mandibles sport.

As a farmer, Eylenbosch’s working life is full of animals and not just insects. His parents have had cows, pigs, and sheep on the farm. In the nearby Sonian Wood, a 4,421-hectare forest on the south-eastern edge of Brussels, he sometimes helps his father, a conservation worker, to look after a herd of highland cattle; a breed recognisable by their hardy, long horns and shaggy coats. Today, he’s kept company on the Sollenberg farm with Stippy the mule, Caramel the donkey, a Flemish Giant rabbit, and his border collie, Loe.

But the stag beetle is his most esoteric passion. It features in pictures hanging at the farm reception area and on Eylenbosch’s Instagram feed. He’s even preserved dead stag beetles and attached them with a needle to a wooden block for easy display. When he was 17 years old, he produced a paper on the insects during his Nature and Environment studies. “I have a real love for the stag beetle,” he says.

In 2020, long after he’d graduated from studying bugs at school, Senne Eylenbosch opened Het Boerenerf on his family farm to indugle his other big obsession—beer. As a blendery and not a brewery, Eylenbosch sources innoculated wort from Lambic breweries, aging the spontaneously fermenting wheat beer in barrels to produce his own fruit blends and Geuzes.

You’d be forgiven for thinking Eylenbosch’s twin obsessions—Lambic and stag beetles—had little in common. But both are indigenous to the valley in which he grew up. The beetles, the largest in Belgium, live in oak in the same way the spontaneously fermented wheat beer does. They have, just like Lambic, faced the very real threat of extinction, but have in recent years staged a revival. And like Lambic, the stag beetle is resilient (the males use their mandibles to fight for females and for food); it’s slow-moving, because of its oversized mandibles; and it’s fragile (they live for only three to five years, more or less the time it takes to produce an Oude Geuze).

When Senne Eylenbosch is talking—and Senne Eylenbosch likes to talk—his musings on stag beetle conservation and the maturation of Lambic could easily be interchanged. “Don’t touch it,” he says multiple times about the stag beetle. “Don’t touch it,” he says multiple times when discussing Lambic. He talks about patience. He talks about respect. He talks about nature. “Don’t touch it,” he says, again and again.

II.

Lambic and Ice cream

Senne Eylenbosch, today twenty-eight years old, lives on his family farm on the Sollenberg. His parents, Paul Eylenbosch and Veerle Samyn, began organic farming here in 2000. For years, their 37 hectares—20 hectares of farm land and 17 hectares of meadow—provided thirty-six cows with the grass they needed to produce organic milk as a basis for the farm’s yoghurt, plattekaas, pudding, and butter. In 2010, the family closed most of their dairy operations to focus on the dairy product for which they had gained a sizable reputation—ice cream: vanilla, chocola, mocha, stracciatella, speculoos, hazelnoot, strawberry, and lemon.

Eylenbosch remembers his mother telling him she would only ever make dairy products if it was his father that had milked the cows. She insisted they use jersey cows for the higher fat yields, even if it meant less milk. The quality of the ice cream took precedence over all.

The family would sell lots of ice-cream at the Kasteelfeest, a summer event famous for its local culinary offering held every two years at Beersel Castle for around 5,000 visitors. At the 2011 Kasteelfeest—when Eylenbosch was 15 years-old—his parents were busy scooping ice-cream and making pancakes, so Eylenbosch sneaked off to the tent next door, where Sidy Hannsens of Geuzestekerij Hannsens pulled him aside and gave him a glass of Hannsens Oude Kriek. She even gave him a five euro note to buy a Kriek from another producer so he could understand how “a real one” tasted against other versions. It was a small gesture that made a big impression on a young Eylenbosch.

Four years later he’d get a taste of his first straight, unblended Lambic, a a six-year-old sample that had been aging in a Cognac barrel and served from a small cask at Brouwerij Boon while he was helping out at Boon’s trade sessions during the bi-annual Toer de Geuze of 2015. “It was like whiskey without alcohol,” says Eylenbosch of the experience. “And I was like, whoa, what is that?!”

Later, he tasted a three-year-old Lambic directly from the barrel at Lindemans, which he says tasted of almonds. “It’s almost a pity this has to become a Geuze,” he recalls thinking. As he continued tasting across breweries, he would come across barrels that produced something more akin to vinegar, realising every barrel is different to the next and that, as far as beers go, “Lambic is not easy.”

Growing up in the Zenne valley, Lambic was always on Eylenbosch’s periphery. The building right next door to where he lived, now a block of apartments, was once a Lambic brewery dating back to the 1860s and owned for a period by his own bloodline. “It was a big scar in the family,” he says of the family’s decision to stop Lambic production in the 1960s. “It wasn’t commonly talked about. It’s still not.”

Initially owned by the Cammaert family, the farm brewery came into the Eylenbosch family when Anna Maria, a great-granddaughter of the brewery’s founder, married Martinus Josephus Eylenbosch in 1874. In 1922, the family’s business interests were divided between their sons—Senne Eylenbosch’s great great grandfathers—with Jan-Baptist and Georges taking over the brewery and Victor taking over the farm. When Jan-Baptist Eylenbosch passed away in 1948, brewery ownership transferred to his son Henri Eylenbosch, who continued making Gueuze until 1965 when the brewery closed. Senne Eylenbosch isn’t sure why the family shut the brewery, but “something happened” and he says there’s a sense of “shame” in the way older members of his family talk about it now.

The farm eventually made its way into the possession of Senne Eylenbosch’s father, Paul. The building where his family made Lambic for generations now stares down over the farm each day, its old production areas converted into residential lofts by architect Steven Winderickx, the son of Lambic brewer Edgar Winderickx. The ice-cream equipment is gone, replaced now by Senne Eylenbosch’s maturing Lambic, blending tanks, and bottling equipment. There are small hop bines on the farm, Groene Bel and Tettnanger which Eylenbosch sometimes uses in his honeywines. Some of these barrels even contain Lambic made with his own grains, the farm maintaining fields of wheat, triticale, and corn as cattle fodder. All in the shadow of the building that once housed the family brewery.

While he embraces the family brewing history, he doesn’t want to be tied to it. “It’s four generations back,” he says. “I will not take on their heritage to sell my beer. I don’t think it’s authentic.” He uses the Flemish phrase, pluimen verdienen; to “earn kudos”, to “deserve your feathers”. But it comes out in English, a little differently: “I want to deserve my own plums.”

III.

Mentors

After leaving school Senne Eylenbosch worked for a period as a nature guide in the Sonian Wood, and for a while thought about becoming a primary school teacher. But then he discovered an interim job opening at a Lambic brewery that had just expanded into a new location in nearby Lot and needed extra hands. Lambic had always been there and this opportunity seemed like a good move. On 7 July 2016, Eylenbosch’s started working at Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen’s Lambik-o-Droom facility. “At 3 Fonteinen, Lambic was a way of life.” says Eylenbosch. “It was ‘all-in’ stuff.”

He remembers his first days at 3 Fonteinen with co-owner Michaël Blancquaert. He remembers cleaning coolships in the morning and bottling in the afternoon. “He was eager to work,” says 3 Fonteinen co-owner Werner Van Obberghen of their first impressions of the young Eylenbosch. In January 2018, they took him on as a full employee.

Eylenbosch would come in at 8am to find Blancquaert already working for several hours. And at 5pm, when Eylenbosch would leave, Blancquaert would always be there to say goodbye before logging a few more hours into the evening. “I never saw the guy leave,” says Eylenbosch. “Unconditional motivation,” Eylenbosch calls it.

He also met Armand Debelder, the brewery’s previous owner who passed away in March 2022 after a two-year battle with cancer. Debelder was not only a respected figure in the world of Lambic, known for his work ethic, highly-regarded palette, and passionate demeanour, but he was also a well-known figure in the local community—Eylenbosch has a particular memory of Debelder dancing with his mother at one edition of Beersel’s Kasteelfeest.

Debelder was officially retired from brewery operations when Eylenbosch started, but was regularly found at the brewery offering advice to his successors, assisting Blancquaert with blends, making sure younger staff were laying bottles into baskets correctly, or seducing visitors with his stories. Eylenbosch remembers one particular tasting session in the blendery with Debelder, where he pulled out a bottle of Geuze made in the 1980s by a now-defunct Lambic brewery called De Neve. The bottle made an impression on the younger man, “Oh damn,” thought Eylenbosch. “This is how I want a geuze to develop.”

Trying these old bottles that had been aging for decades would give Eylenbosch ideas for different Lambic blends. On one occasion, noting a distinct hazelnut in some vintages, he tried to create a Lambic with actual hazelnuts. Eylenbosch had spent hours working on the blend, and in a fit of excitement, when it had sat in a barrel for just three weeks, he brought it to Debelder, a thick glass of cloudy, white haze. Eylenbosch says Debelder took the glass, looked at it, and immediately pushed it back across the table. He remembers Debelder’s next words as follows: “If you don’t respect it enough to age it, I will not even taste it.”

Eylenbosch understood immediately. If he didn’t respect the Lambic enough to give it time, then he wasn’t in the right place.

IV.

Blends

Senne Eylenbosch’s Lambic blends are an expression of his obsessions.

Like his mother’s insistence on only making ice-cream from dairy of cows milked by his father, Eylenbosch likes to use fruit only from farmers with whom he has a personal relationship.

There’s Lode Meerts of De Seepscherf from whom he sources quince for his Kwee blend. There’s his brother Joppe, three years his senior, who works on the organic farm Het Neerhof and who provides him with rhubarb for his Rabarber blend. Bart van Parijs of the organic fruit farm Purfruit supplies him with blackberries and blueberries for his Braambes and Bosbes blends. Hannes Van Den Bossche of organic fruit farm De Daalkouter keeps him in stock of four varieties of raspberries for a Framboos blend. And then there’s Peter Vandaele who runs three orchards and provides apples for Het Boerenerf’s cider blends.

When Senne Eylenbosch blends, he’s looking for a balance of bitterness, acidity, mouthfeel, and aroma. It’s what he calls his “base”, the foundation of his understanding of the process of Lambic blending. “I really dislike if your aroma and your body don’t combine together,” he explains. “If it’s too fruity in the nose, and it’s too slow-drinking in the body—because body is also one of the reasons that something is very slow drinking—it fights. It’s not good when the aroma is not in character together with the body.”

Although skilled in traditional blending, Eylenbosch also experiments. He blends Lambic with beetroot he grows on the Sollenberg farm, and with grapes, redcurrants, and peaches he sources from farmers he knows in Italy. He ages Oude Kriek in atypical vessels like Amarone and Recioto wine casks, as well as in Bourbon barrels.

Het Boernerf’s Symboise, a blend of Lambic, Cider, and Mead showcases a trio of fermentations: grains, honey, and fruit. Zomerkriek begins as cherry Lambic, but rather than being blended back with young Lambic as would be the traditional way to make a Kriek, is blended with young cider. And then there’s Oude Cider, an old cider made from Norman apple varieties which is aged for 17 months in Lambic barrels, blended with young cider from Pajot orchards and then aged again for six more months in Lambic barrels.

Though he’s confident in how he blends his beers now, a confidence which shines through in the final product, for a long time it was never his intention to to go out on his own. He thought he might do something solo when he was older —“When I know who I am,” as he puts it—but not in his twenties. Then something happened that forced him to make a choice.

V.

A Matter of Time

In 2019, Senne Eylenbosch’s mother Veerle Samyn left the Sollenberg farm after divorcing his father. She took the ice-cream business with her and so Paul Eylenbosch had to make the farm work economically without an crucial source of revenue. There was no possibility of farm expansion as the land had been designated as zonevreemd, meaning the government, over time, intended that the area be for residential living only. The financial stability of the farmstead and the future of the land on the Sollenberg were in doubt.

Senne Eylenbosch was 23 years old. Someone would have to buy out his mother’s share in the farm ownership and run a business that would make enough money to keep it going. “I’m too young,” Eylenbosch says of his thinking at the time. “I don’t want to take that responsibility. I don’t have the cash or the money or the knowledge.”

But Eylenbosch also knew that if he did nothing, the farm would have to be sold, most likely to someone outside of the family.

He talked with the leadership at 3 Fonteinen. They were supportive, but wanted him to make a decision as quickly as possible so they could make arrangements to cover his position if he left. “I’m way too egotistical,” says Eylenbosch. “I have to do it myself. I got to do my thing.” Senne Eylenbosch officially left 3 Fonteinen in the summer of 2020.

Around the same time, one of Eylenbosch’s relatives reached out to rekindle conversations about the old family brewery. They asked him whether he wanted a stave from one of the old family brewery’s foeders that had been used to mature Lambic, complete with a metal plaque indicating the foeder number, No. 478. The stave had been sitting in the cellar of his relatives’ house since the brewery closure in 1965 and, given Eylenbosch’s plans to start his own Lambic business, he wondered if Eylenbosch would like to have it. “Of course I want to have a piece of heritage back,” he said.

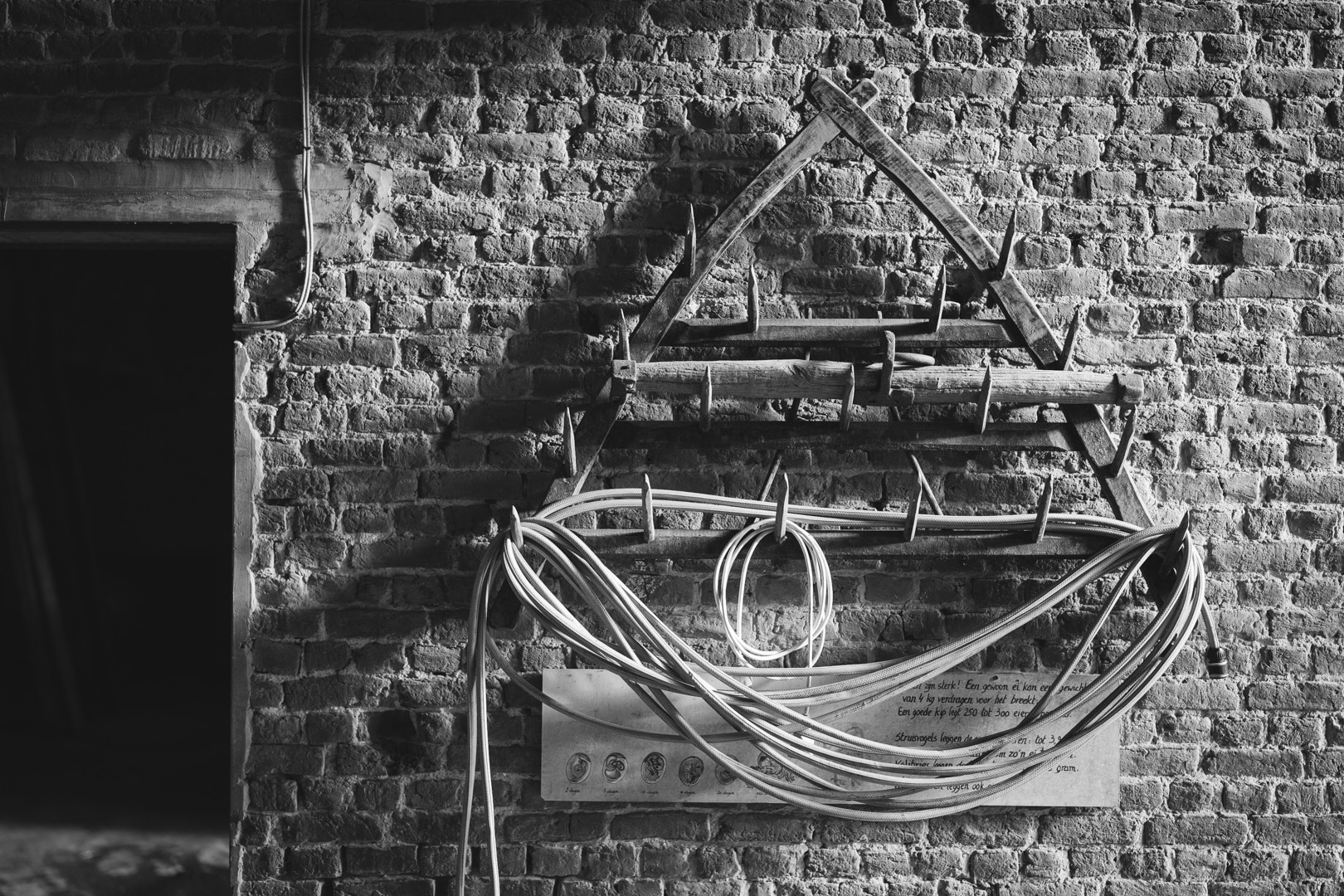

There were other pieces of heritage from the old brewery that turned up too: wooden crates, a barrel ladder, a barrel brush, a brewing fork, glassware, and old bottles of Gueuze. These old bottles had labels with an image of the cap of the maltings and brewery chimney. The chimney, which still stands today but without the cap, was an iconic visual at the busy Sollenberg crossroads.

Eylenbosch also had the “tonmerk” or “barrel mark” of the old brewery: a series of “U”-shaped waves that denoted that the Lambic inside was theirs. Eylenbosch says that each “U” shape in the tonmerk symbolises one generation of brewery ownership.

But there was one piece of family history Senne Eylenbosch would not be able to use in his new venture: the name.

Another Lambic brand had launched in 2019, the owners of which would resurrect a different family brewing heritage, and they’d trademarked that family name in 2011 for use in beer, alcoholic drinks, and drinks distribution.

The name? Eylenbosch.

VI.

Eylenbosch

Brouwerij Eylenbosch of Schepdaal was founded by Emile Eylenbosch in 1886. One year earlier, Emile’s nephew Martinus Eylenbosch had taken over the Cammaert brewery. But whereas Martinus’ brewery would remain a small farm brewery affair at the Sollenberg, the Schepdaal brewery would grow to be one of Belgium’s largest Lambic and Geuze producers in the course of the 20th century.

Brouwerij Eylenbosh was bought out by the De Keersmaeker family and the brewery in Schepdaal closed in 1991. That family kept ownership of the brand, and in 2019, Erik De Keersmaeker ressurected it. De Keersmaeker began by brewing top-fermented beers to raise funds for Lambic production. The Patience beers—Saison, Pale Ale Speciale, and Blond—are brewed at De Ranke. Today, Eylenbosch Lambic is produced at De Troch, matured in a barn in Zellik (20 foeders of 5,000 litres), and packaged at Brouwerij Strubbe in Ichtegem.

No-one involved at Brouwerij Eylenbosch carries the name today. “We bought it from the second or the third generation [of the Eylenbosch family],” says De Keersmaeker. “If my name would be Senne Eylenbosch, I would also like that my beer would be called Eylenbosch,” says De Keersmaeker. “I can honestly understand that this frustrates Senne a little bit. But for me, that’s one of the biggest assets, that brand. And, that, he understands.”

When the Brouwerij Eylenbosch brand was relaunched, De Keersmaeker and Senne Eylenbosch exchanged emails. “Until now we’ve never been arguing with each other,” says De Keersmaeker. “He’s right in his shoes, and I’m right in my shoes, and I respect him, really. And I think he makes fabulous things and also has nice branding and is completely different from the others.”

Senne Eylenbosch admits he was originally uneasy about the fact he wouldn’t be able to use his own name. “When I started here on the farm, I was a little paranoid about it,” he says. “How was I going to talk about this?” But he understands and accepts the situation, and he’s philosophical about it.

“We look forward to the future,” says Eylenbosch. “I’m not selling beer from a brewery which once existed. I’m from 1995. The brewery stopped in 1965. That’s 30 years difference. I’ve never seen the brewery.” But he didn’t want to totally dismiss his family heritage, and so he chooses to take inspiration from the Geuze labels, barrel mark, and the stories he has been told by his grandparents of the old Lambic brewery which used to exist right beside his farm.

All of these considerations and dilemmas—respecting the heritage of the old brewery without relying on it; embracing his identity as a farmer; doing his own thing and not listening as much to older voices—they all coalesce in the name he has chosen for his blendery: Het Boerenerf. In Dutch, it has a double-meaning. It translates directly as “The Farmstead”. Senne Eylenbosch is a farmer, just like his father, his grandfather, and his great grandfather before him. But the word Erf in “Boerenerf” also refers to Erfgoed, meaning “Heritage.”

VII.

Reclamation

In January 2020, Senne Eylenbosch started work on Het Boerenerf. He knew that if he acted fast, he could buy wort produced during that year’s Lambic brewing season. Otherwise, he’d have to wait more than half a year for the next season to start. He’d learned from Armand Debelder that time was a crucial factor in making good Lambic. He sourced ten barrels to get started, filling them with wort from 3 Fonteinen.

Sometimes, lying in bed, Eylenbosch would have “small panic attacks” thinking about all the things that could go wrong. “It’s going to be okay,” he told himself. “It’s going to be okay. Take your torch and go check out the barrels.”

Realising that he would need help on the commercial side of the business, Eylenbosch partnered up with Vincent Alluin, a fellow 3 Fonteinen alumnus with commercial experience. Alluin is Eylenbosch’s “Boerenerf other half”, someone who acts as his “filter”. “He makes sure the boat stays afloat and headed on course,” says Eylenbosch. He admits he needed a partner: “Do you want to do it on your own and be bitter the rest of your life and always angry with everyone else because you don’t know how to get the company up and running,” he says he asked himself. “Or do you also want to have a wife and children and a future?”

Senne Eylenbosch’s father Paul is the “concierge of the farm”, in the words of Eylenbosch. “He makes sure I get to do what is important,” he says. “He’s very supportive, which is not so traditional on family farms.” The team has continued to expand in the four years since Eylenbosch started. Loick Bekaert was hired in May 2023 to assist with sales and marketing. Timothy DeTemmerman is a local 18-year-old farm-hand who has been helping at the Sollenberg since the age of 10. “He drives tractors and loves everything with machinery,” says Eylenbosch. Benoit Gilert started in November 2023 to assist with production. “Benoit is my right hand as Loick is Vincent’s,” says Eylenbosch.

He’s also had visits from other Lambic producers keen to see what’s going on at the Sollenberg farm: Pierre Tilquin of Gueuzerie Tilquin; Karel Goddeau of Geuzestekerij De Cam; and Gert Christaiens of Oud Beersel. Alluin invited their former employers at 3 Fonteinen to come take a look too. “We think that the location is, in one word, wonderful,” says Eylenbosch’s former employer Werner Van Obberghen. “It is a nice addition to the Lambic landscape.”

Eylenbosch says that he’s undecided about whether he might, if asked, join HORAL—the High Council of Artistanal Lambic Producers, an association founded in 1997 whose objectives are stated as being the promotion and protection of artisanal Lambic beers. Eylenbosch’s mentors at 3 Fonteinen left the organisation over disputes about how HORAL goes about achieving these goals, but he respects many of the HORAL members and there are undeniable commercial benefits to being involved, whether that’s official involvement in the bi-annual Toer de Geuze or access to estabilshed distribution channels.

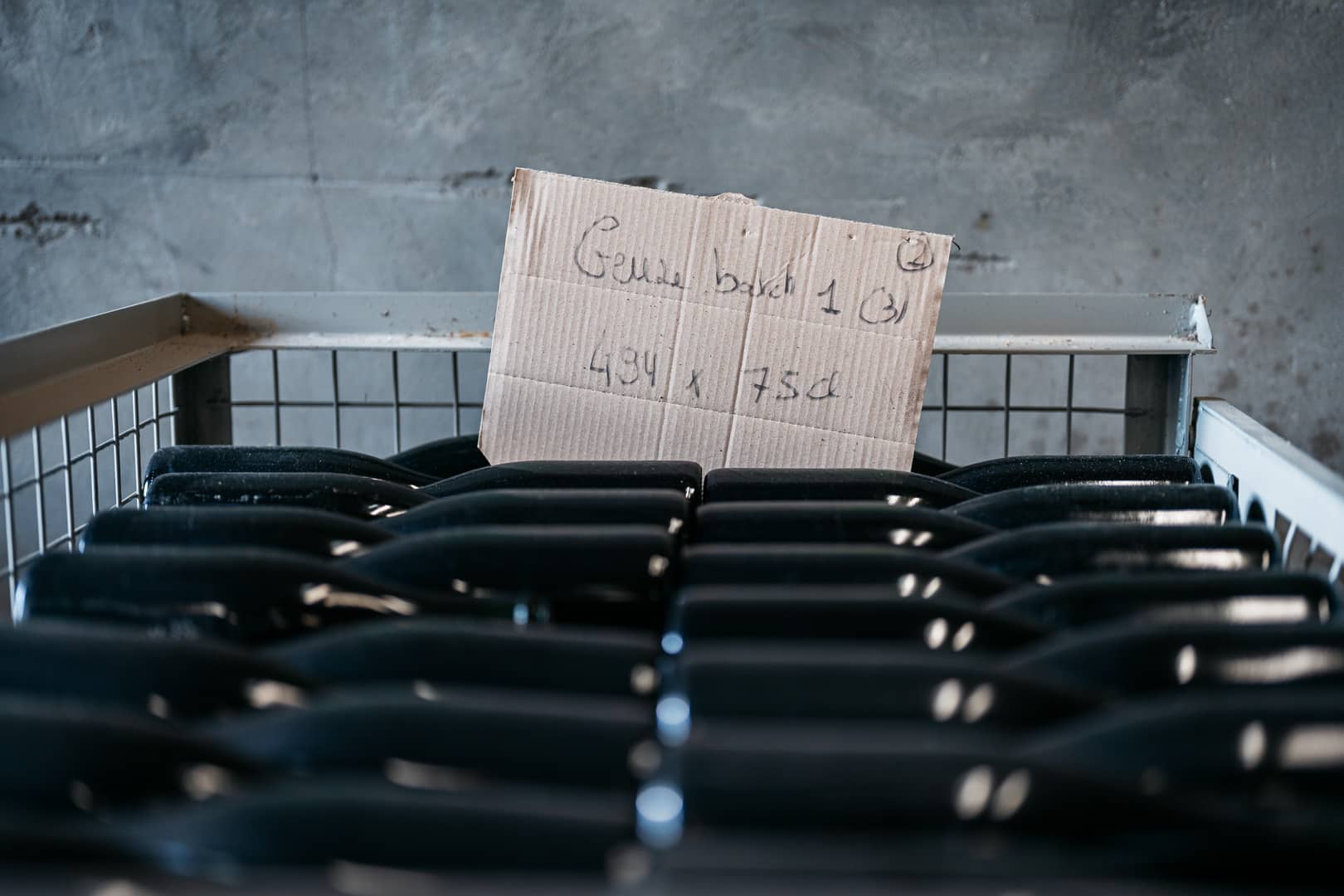

Today, Eylenbosch and his team at Het Boernerf are responsible for 160 barrels of various sizes ranging from 220 litres all the way up to 750. They source their wort from 3 Fonteinen, De Troch, Angerik, Lindemans, and Den Herberg. They released 21 different blends in 2023 and the blendery is now focusing on growing production and stock. “Now we have beautiful barrels with beautiful Lambic and beautiful bottles,” he says. “Looking back, it’s been a beautiful transition from 3 Fonteinen into developing my own stuff.”

Alongside its many fruit blends, Het Boerenerf releases two Geuzes every season.

The first is Cuvée Heritage, a beer Eylenbosch describes as “a traditional assemblage of young and old Lambics.” It’s claimed to have “exceptional complexity and storage potential.” The label for the Geuze—spelled in the French manner Gueuze as was the case at the old Huizingen Eylenbosch brewery—is an almost identical replica of the label of that historical beer: the cap of the old chimney which was for so long an iconic visual symbol of the Sollenberg crossroads.

The second is Het Boerenerf’s standard Geuze blend, described as a “malse” or soft Geuze and blended to be “more easy drinking”. On the label is a colourful illustration of a stag beetle by Italian-Russian artist Anna Yudina. The beetle stands on an oak branch, its head looking upwards and outwards, its toothed mandibles ready to protect itself against anything that might try to touch it.

*