“The Session, a.k.a. Beer Blogging Friday, is an opportunity once a month for beer bloggers from around the world to get together and write from their own unique perspective on a single topic. Each month, a different beer blogger hosts the Session, chooses a topic and creates a round-up listing all of the participants, along with a short pithy critique of each entry”.

“The Session, a.k.a. Beer Blogging Friday, is an opportunity once a month for beer bloggers from around the world to get together and write from their own unique perspective on a single topic. Each month, a different beer blogger hosts the Session, chooses a topic and creates a round-up listing all of the participants, along with a short pithy critique of each entry”.

At Belgian Smaak, we are hosting this month’s Session entitled ‘My First Belgian’, for which we are writing about Westmalle Tripel.

MY FIRST BELGIAN

On my first visit to Belgium I found myself sitting with Elisa and two of her friends at an old wooden table in Den Bras, a small biercafé in Kortrijk opposite the train station. It’s a pretty nondescript train station bar with a red brick interior and a beer card which might be found in any West Flemish café.

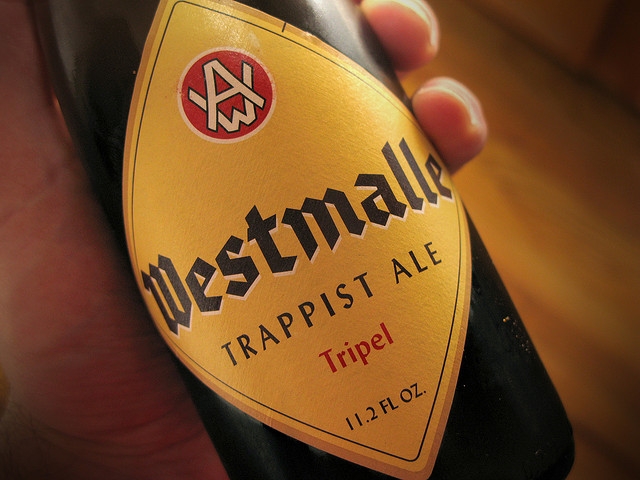

I can’t explain why I picked it. Westmalle Tripel.

It’s a solid name. Westmalle sounds like a place full of people who won’t let you down, not like those flakes over in Northmalle. There’s something about the bottle with its ringed neck and embossed lettering, a beautifully antiqued golden label. It arrived at my table in its crystal chalice, rows of dimples around its base. The rest, as they say, is history.

THE TRAPPIST ABBEY OF WESTMALLE

Photo by Travlr / CC BY

A good indication of what the monks at the Abbey of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart were trying to do when they created Westmalle Tripel comes from the name they gave to it when it was first brewed in 1934. They called it ‘Superbier’. You don’t need the English translation.

The ‘Trappist’ in the ‘Trappist Abbey of Westmalle’ refers not to the style of the beers they produce, but to their origin. At time of writing, there are only ten ‘International Trappist Association’ recognised breweries in the world: Stift Engelszell in Austria, Spencer in the U.S., La Trappe and Zundert in the Netherlands and the six Belgian Trappist Abbeys: Achel, Chimay, Orval, Rochefort, Westvleteren and of course, Westmalle.

Photo by Craige Moore / CC BY

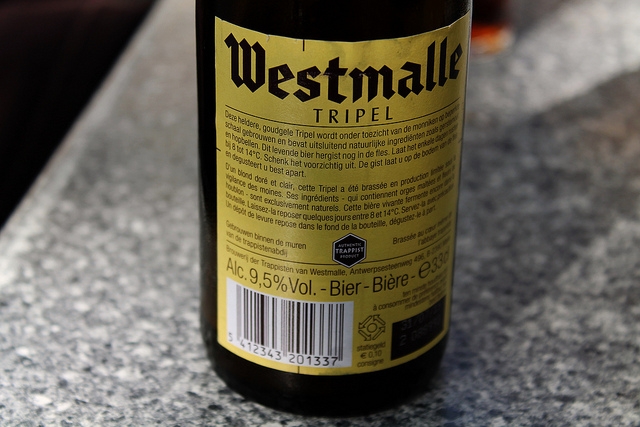

Each of these abbey breweries, including Westmalle, must fulfil a number of criteria to maintain their status and keep the ‘International Trappist Association’ logo. These criteria require that the beers be brewed within the walls of a Trappist monastery under the direct supervision of the monks and that the biggest part of the profits go to support the monastic community. The ‘International Trappist Association’ logo should not be confused with the ‘Certified Belgian Abbey Beer’ logo which was introduced by the Union of Belgian Brewers in 1999. This one is granted to beers brewed under licence to an existing or abandoned abbey and is intended to mark these beers out from those which just stick a local saint on the label or imply other tenuous religious connections.

A ‘SUPERBIER’

Photo by Christopher Lehault / CC BY

The ‘superbier’ that was brewed in the 1930s would go on to become the classic ‘Golden Tripel’. The recipe was modified in 1954 and the beer renamed ‘Westmalle Tripel’. Westmalle maintain that the recipe remains the same today as it did in 1954.

The term Tripel refers not, as many believe, to the beer having been triple-fermented or to there being three times the amount of malt than that of the monk’s normal beer. Rather, it follows a historical system of labeling a beer by strength.

At a time when most people in Belgium couldn’t read, casks of beer were marked to indicate how strong they were, usually with a series of crosses. The weakest, sometimes referred to as ‘pater’ beers, which were for consumption by monks, were generally marked with one cross (X). The stronger beers, ‘Dubbels’, were marked with two crosses (XX) and the strongest, the ‘Tripels’ with three crosses (XXX). Today, ‘Tripel’ might be seen as a reference to the use of raw materials in the recipe that are larger in quantity than usual and they are often brewed to follow the style first espoused at Westmalle. ‘Quadrupel’ beers (also referred to as ‘Abt’ beers in Belgium) have emerged as well which follow the same logic.

At the time Westmalle was first brewed, the monks had some help from Henrick Verlinden, a brewer in his own right and consultant to the Abbey. Back then, stronger beers were generally darker in colour. The use of pale malts in the Westmalle Tripel not only resulted in something resembling a pils beer, but the taste of such stronger beers changed from having the caramel notes associated with darker malts to the crisper flavours of the paler malts.

Photo by VisitFlanders / CC BY

The Westmalle Tripel also made use of candi sugars which contributed both to more sweetness in flavour as well as to a higher level of alcohol. A subtle hop character was also introduced, using fresh hop flowers rather than pellets to provide a balanced background bitterness.

The Westmalle yeast tolerated high levels of alcohol and attenuated well (meaning that it enjoyed a high rate of conversion of sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide during fermentation) and this generated a desirable range of phenolics and esters (those wonderful spicy and fruity aromas in a beer which derive from the type of yeast).

Combine this with their technique of bottle conditioning and the monks were left with a pronounced natural carbonation in their beer to the extent that it is sometimes called the ‘Champagne Campinoise’ or the ‘Champagne of the Kempen’.

WESTMALLE TRIPEL (9.5% ABV)

Photo by VisitFlanders / CC BY

Westmalle Tripel pours a cloudy golden yellow with a white foamy ice-cream head and wonderful lacing along its chalice glass.

The aroma is dominated by fruity esters; mostly banana, apple and then some more banana. Accompanying this sweetness, there is a subtle hint of spicy pepper and a bready biscuit that is often associated with Belgian yeast strains of the type used by Trappist monks.

All of that fruity sweetness is there in the taste, freshly baked white bread, peppery spice and a hint of flowery hop. The beer is dry and the mouthfeel creamy, full-bodied and well carbonated.

SECOND AND THIRD TIMES

Photo by Michael Costa / CC BY

That first evening when I tasted Westmalle Tripel in Den Bras was a special one. There is no other Belgian beer that I’d rather have called my first.

If you haven’t tried ‘the mother of all Tripels’, you should give it a go.

But a word of advice. Don’t drink five of them in a row.